So you’re probably aware of the most common fiction genres—fantasy, science fiction, and horror on the speculative side, the entire mystery umbrella (covering crime, thrillers, cozies, noir, etc.), as well as literary fiction as a whole. But for me, somebody who has been writing professionally for the last 14 years, it’s the subgenres that hold my attention, the fringe stories and tales on the periphery that really get me excited to sit down and write, as well as read. Here are some of my favorite subgenres, and the aspects of them that I find to be original, compelling, and enticing.

As a reader, and viewer, of contemporary dark stories, I’m most drawn to work that does not sit nicely in the middle of a major genre. I’m drawn to the periphery, the edges, the shadows, and cobwebbed corners. And these three subgenres—neo-noir, new-weird, and hopepunk—all have those traits in common. They are looking to pull us in with techniques, tropes, rules, and histories that are familiar–so we’ll know how to access these works, how to set up our expectations. And then…they subvert those expectations. Not with deus ex machina twists that come out of nowhere, but with unique moments, surprises that feel fated, and endings that are earned. And I think it’s okay to be polarizing, too. As a writer, I’d rather have half my audience hate what I did and the other have love it, then have 90% think it was just okay. And I think the films coming out from A24 and Neon, television shows like Squid Game and Midnight Mass, and books being written by award-winning authors such as Stephen Graham Jones, Usman T. Malik, A. C. Wise, Brian Evenson, and Kelly Robson are doing the same thing. They are honoring the past, pouring themselves into the work, and then taking us someplace new, inspired, and unsettling. And isn’t that why we’re here?

NEO-NOIR

I thought I’d start with neo-noir since this is Crimereads after all. It’s also one of the main genres I first wrote when I started to get serious about writing, at the age of 40. If you’re familiar with film noir, or noir in general, then you probably know the expectations of that genre—some cop or private eye, a hard drinking, smoking loner, whose life is filled with bad guys, femme fatales, these dames with gams, and all manner of black and white drama. And that’s totally fine, it’s a thing. But what I find more interesting is neo-noir—which just means “new-black.” It takes the bleak vibe, the atmosphere, the tone and mood of noir, and pushes it into new, exciting direction. When I was first trying to find my voice, I ran across several authors that really woke me up and showed me what was possible. You probably know the most famous, Dennis Lehane (Shutter Island), but I was also blown away by authors like Will Christopher Baer (Kiss Me Judas), Craig Clevenger (Dermaphoria), and early Stephen Graham Jones (All the Beautiful Sinners). If you want to look at film, you could tap into everything from Blade Runner and Memento to Mulholland Drive and Seven.

Neo-noir can lean into science fiction, and horror, as well as all manner of mystery (especially thrillers) but typically it remains rooted in gritty realism. Angel Heart is one of the few supernatural exceptions I can think of. With neo-noir you must do something new—a new updated cast of characters who break our preconceived notions of work, gender, and roles; the formula and structure of your story, doing something unique with it; perhaps the location you are setting the story, not the same old dirty cities; and the plot of course, pulling us in with familiar tropes, and then subverting the expectation. The first anthology I edited, The New Black, ran the gamut, with stories that were originally published in a wide range of magazines and journals. Some of my favorite authors in that anthology were Benjamin Percy, Brian Evenson, Paul Tremblay, Lindsay Hunter, and the aforementioned Stephen Graham Jones. And this anthology showcased work that originally appeared in places like Conjunctions, Cemetery Dance, Fantasy Magazine, Surreal South, The Missouri Review, and Barrelhouse.

THE NEW WEIRD

Over time, my neo-noir evolved and changed, and turned into more speculative and supernatural work, so the new-weird is a subgenre that has really become a large part of my focus these days. It differs from neo-noir in that it is quite often NOT grounded in a gritty reality, but pushed into someplace dark, strange, and surreal. The new-weird started with the old weird (which most define as Lovecraft), and then adds in the visceral body horror of authors like Clive Barker (Weaveworld). The novel that kicked off the movement was Perdido Street Station by China Mieville—a sprawling, epic, original mix of fantasy, science fiction, and horror. That’s one of the books I teach in my Contemporary Dark Fiction class. And another, Annihilation by Jeff VanderMeer, takes that new-weird mantle and runs with it. In the new-weird you tap into the uncanny, the surreal, the cosmic horror of stories that shift and change and slide from one emotion and reality into another. These stories are weird, for sure, strange tales, but not just bizarre for the sake of being bizarre, grounded in their own set of rules, atmospheres, and unsettling endings. I’m not a huge fan of Lovecraft, but I do love Lovecraftian stories, so I’m drawn to those that can take the old gods, and eerie locations, and then show us something new and different. I think of stories like “Between the Pilings” by Steve Rasnic Tem, and “Harvest Song, Gathering Song” by AC Wise, and just about anything by Brian Evenson (but especially his novella, The Warren).

In the new-weird you tap into the uncanny, the surreal, the cosmic horror of stories that shift and change and slide from one emotion and reality into another.What the new-weird is NOT, is a story or novel that is nicely centered in horror, or fantasy, or science fiction. It’s on the periphery, the edges, sliding in and out of focus, balancing the concrete with the abstract, working hard to show you something you may never have seen before. I think of so many aspects of Perdido—the slake moths, the torque, the Weaver, the Ambassador to Hell. I think of moments in Annihilation that I’d personally never witnessed—not the bloody violence of werewolves and demons but the eco-horror of green moss, nature encroaching, and the appropriation of human cells, creating all kinds of alien creatures and moments. It’s taking tropes and settings and characters that might start out familiar, and then leading us down a path to a field filled with animals and flowers that don’t exist in our lexicon, and maybe shouldn’t exist at all. It’s often unsettling, and surreal, with a rippling, expanding finish that haunts us after the story is done. This is what I’m drawn to these days, in what I read, and what I write, more than any other subgenre.

HOPEPUNK

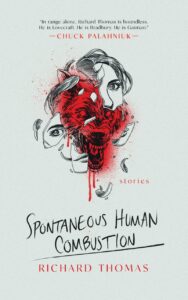

Another aspect of my craft that has been developing over time is the desire to write with more hope in my dark fiction. My upcoming collection, Spontaneous Human Combustion (Turner Publishing, 2022) contains quite a few stories that work in hope amongst the dark tales and violent images. Whether I’m writing a horror story about a bad man who has a change of heart in order to save his dying son (“Repent”) or a fantasy world that shifts to bleak reality (“Hiraeth”) what I’ve been drawn to these days is the idea of hope, in the middle of the horrific. The punk suffix attached to the word hope here (which you may have seen in other subgenres like splatterpunk or cyberpunk) just means some rebellious trait, something anarchistic, or anti-authoritarian, that pushes back against the norms. So in this instance, the hope is pushing back against the very nature of the story it’s in! Horror with hope, bleak noir with hope, dark fantasy with hope, dystopian science fiction with hope.

Over the last four years, as there has been so much political turmoil in the world, not to mention the Covid outbreaks, I just couldn’t find the emotion and energy to write dark, bleak stories. I had to find some light in the gloom, something to root for, to walk toward, to instill some faith and optimism. For me, the hope might manifest in some lighter moments throughout a darker journey—giving us peace and love and friendship as the darkness encroaches. It might be in the ending to a story, where the resolutions and denouements speak to positive change—everything from a belief in a better tomorrow, to the eradication of a certain evil, to the spontaneous evolution of the human race. It’s not just tacking on a happy ending to a sad, dark, bleak story. It’s earning that ending, it’s putting love in the center of a horror story instead of death, it’s looking for light to offset the dark.

I just finished writing my fourth novel, which is tentatively titled Incarnate. It’s an arctic horror novel with a sin-eater protagonist, and it’s definitely dark and strange and violent and unsettling, but I knew going into this that there would be a shift in tone, and that the absolution of the sin eating might be replaced with consequences for those that deserved it, and something brighter and more hopeful for those that were more righteous. It’s a balancing act, but I’ve found that the horror stories that most upset me, disturbed me, and stayed with me, were the ones with the most love, the deepest connections with characters, the stories where I could empathize and sympathize. That goes for mysteries, too, as well as fantasy, science fiction, etc. I think of the end of the film Arrival, or the story collection Jesus’ Son by Denis Johnson, or however you interpret the endings of The Witch and Saint Maud. Wouldst thou like to live deliciously? I would.

***