Murder is boring.

As fictional crimes go, it’s overexposed, overdone—common. A fictional detective can’t walk ten feet without tripping over a dead body, and most of them are only too eager to risk their lives finding out who did the deed. Investigating a killing is fine every once in a while, but any PI who makes a habit of it is not a PI you can trust.

That was my thinking, anyway, when I dreamed up Gilda Carr, star of my 1920s mystery novels Westside and Westside Saints. I wanted a detective who would respond to murder like any sensible person would—by running in the opposite direction. Instead of wasting her time on dangerous, dull, messy murders, Gilda focuses on tiny mysteries: the unassuming little riddles that can ruin a life as surely as a knife to the gut.

In Westside, a merchant’s wife hires her to find a missing white glove. In Westside Saints, a printer of religious tracts engages her to find a particular shade of blue that has haunted him since childhood. The life of a fictional detective being what it is, Gilda’s tiny mysteries tend to drag her into larger ones, but to tiny mysteries, she will always return.

I did much of the research for these novels by wading around the New York Times archives for 1921, and that research soon took on a life of its own, becoming Strange Times, my newsletter, which chronicles the weirdest news of that very unusual year.

In reading the 1921 Times, I’ve encountered countless murders, heists, and daylight shootouts. But my all-time favorite mysteries are tinier than that. Here are five of the weirdest little mysteries I’ve encountered in the ’21 Times. Some are criminal, some are simply odd, and all would make Gilda Carr smile.

*

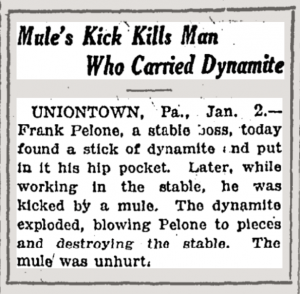

One of my favorite news items of all time, this story runs just 48 words, including the dateline, and contains enough mystery to keep me thinking about it for the rest of my life. It tells the sad story of Frank Pelone, a Pennsylvania stable boss who had a stick of dynamite in his pocket when a mule kicked him in the side.

“The dynamite exploded, blowing Pelone to pieces and destroying the stable,” writes the Times. “The mule was unhurt.”

How on earth could the mule escape from such an incident unscathed? Like the true identities of Jack the Ripper or the Zodiac Killer, we will simply never know.

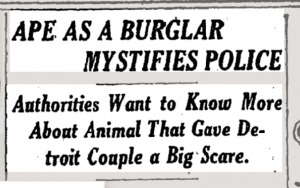

When Fred Grossman saw the face of a truly hideous burglar looming outside his bedroom window, he did the only thing he could think of, firing at it with a revolver until the intruder dropped out of sight with “a half-human scream.”

Following the blood, the police discovered the monstrous criminal was actually an ape who had escaped its owner. They captured the animal and announced their intention to investigate its previous owners, out of fear that they had trained it as a burglar.

“It is peculiar that the ape should have gone to a second story window when there were windows open on the first floor,” said the detective. “An ape can be trained to do nearly anything.”

On January 10, 1921, John Joseph Shortell spent $4.75 on a pair of chickens to make a fricassee. When they were nearly done, he went for a walk “to stimulate his appetite.” On returning, he found the fire escape window forced open. His chicken dinner was stolen, and his best pot along with it.

Shortell was incensed. He had been robbed before, but this really hurt.

“He had $100 stolen a month ago, but that was only money,” reports the story’s unnamed author. “This was chicken.”

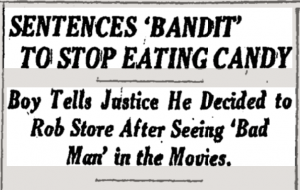

When $13 worth of chocolate and cigarettes went missing from railway offices in White Plains, railroad detective John Roberts threw himself into the case with a fervor that would make Gilda Carr proud.

Informed by the local school superintendent that Bernard Connolly had been truant more than any other student, Roberts and his colleagues tailed the twelve-year-old to a shack in the woods that was littered with cigarette stubs and chocolate wrappers. They arrested Connolly, who claimed his crime had been inspired by “the exploits of a ‘bad man’ in the movies,” and who was sentenced to a year without chocolate by the evocatively-named Justice William Sinn.

“You’ve been a bad boy,” said Sinn, “but you can be good, and I’ll give you a chance. But don’t eat any chocolate.”

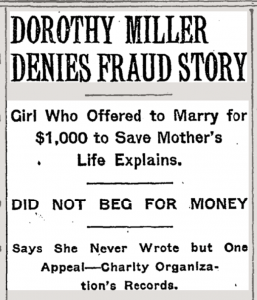

The Strange Case of Dorothy Miller

In March, 1921, a young woman named Dorothy Miller caused a sensation when she offered to marry “any white man” in exchange for $1,000 to pay for her mother’s operation. After rejecting several suitors, including “a Spanish instructor [whose] expressions of love were so passionate and extravagant that she said she did not want to meet him,” she was saved from her plight by the Shuberts, who offered her $1,000 for a one-week engagement at the Winter Garden, “in which she sings a little song.”

This happy ending turned sour when rumors emerged that Miller was a scam artist who had spent years conning generous strangers into giving her money for operations for a mother who, as far as anyone could tell, was in perfect health. Miller denied all charges, but the public turned on the alleged fraudster, whose final moment in the limelight came when the legendary Marie Dressler taunted her on-stage in song:

“It’s spring and I’m full of syncopation,

“’Cause I got a thousand dollars for my mother’s operation.”

Whether Dorothy Miller was telling the truth is a mystery only Gilda could solve.

*