I’m coming from an unusual place as a debut thriller-writer, in that I’ve already written half a dozen books of non-fiction about different aspects of tech culture: video games, the history of digital ideas, philosophy of technology, political protest, online language. But I’m also a geek steeped in cyberpunk and speculative fiction, and I love the idea that techno-thrillers can work a kind of alchemy: that they can weave something abstract and ultra-modern into the oldest kind of story.

I’m also, I ought to add, both delighted and terrified finally to find myself a novelist after almost a decade of full-time writing—and a lifetime of wanting to find an audience through fiction. I couldn’t believe quite how difficult writing fiction was compared to non-fiction, perhaps because reality can’t do any of the heavy lifting: the world you create has to stand up on its own terms, or fall flat. And then there’s that word—“thriller”—with its blunt promise that readers will be thrilled; that they’ll be driven by sheer narrative force to keep turning pages. If you don’t deliver on that front, it doesn’t really matter what else you do well.

As someone who spent their teens eating up sci-fi and fantasy, I particularly love writers who bend or break the barriers between genres, and I guess I see techno-thrillers in these terms: as a fertile colliding ground for technology, conspiracy, crime, politics, the factual and the fantastical. If you’re interested in crime, today, you need to be interested in technology—because we’re living at a time where the kind of crimes being committed, and what it means to obey or break the law, are being rewritten in the form of code. Information itself is the battleground. It’s strange and terrifying and marvelous—and the gift of fiction is to make its urgency feel real, human and tractable.

Hacking the modern thriller: the Millennium trilogy, by Stieg Larsson

The daddy of the modern techno-thriller, for me, is Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy (2005 to 2007)—and the character of Lisbeth Salander in particular. She’s a hacker who bursts into what might otherwise be a down-the-line tale of wealth and corruption: her skills a kind of black magic, inexplicable and irresistible beneath the book’s surface. There were plenty of fictional hackers before Lisbeth Salander, but the Millennium trilogy feels like the first time the crime thriller was itself hacked on such a wildly successful scale. Poor old Michael Blomkvist plays second fiddle in his own story, stumbling in the wake of Lisbeth’s revelations. Her power and fascination crackles through the series, an emblem of the transformations surrounding power in the modern world.

Mainstreaming the hacker dream: Neuromancer, by William Gibson

It’s difficult to write about cyberpunk without mentioning William Gibson’s era-defining 1984 debut. Its sheer influence also makes it difficult to recapture how bold and brilliant his near-future vision was at the time, popularizing both the word and the notion of “cyberspace” alongside a virtual reality realm known as the matrix and the prospect of a rogue AI hauling itself into consciousness. Absurdly prescient, it’s also a fantastically engaging read.

Iconic absurdist cyberpunk: Snow Crash, by Neal Stephenson

Neal Stephenson broke through in 1992 with this mythological mashup of technology and epically speculative world-building. It’s fast and smart and powered by nuclear isotope batteries—and gave us, among other things, the notion of users entering a collective virtual world in the form of avatars, a word then largely used to mean “incarnation” in Hindu scriptures. If Gibson kicked cyberpunk into the mainstream, Stephenson evolved and subverted it into something culturally capacious; a giddy mélange of ancient and modern.

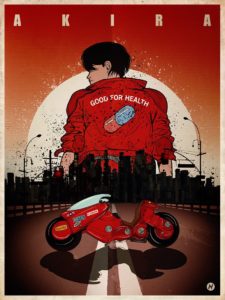

Beautiful and bizarre: Akira

I first watched the film based on Katsuhiro Otomo’s ground-breaking manga series in the early 1990s, understood nothing of what was going on—and couldn’t take my eyes off the unfolding apocalyptic tale onscreen, with its mix of slick tech, body horror, wizened children and dream-like lacunae. Translated into English between 1989 and 1995, Otomo’s vision of Neo-Tokyo seared a distinctively Japanese vision of cyberpunk into the world’s consciousness, spawning countless imitations—but few able to match its visionary intensity.

Taking it beyond the limit: Accelerando, by Charles Stross

I’m a huge fan of Charles Stross, and this is my favorite of all his wonderfully wild imaginings: a series of short stories showing the accelerating impact of technology before and after the singularity, as it lurches vastly beyond humanity’s capacity to comprehend or control it. Plenty of people have written about similar themes—but Stross pushes them further and harder than anyone else, with unflagging imagination and an eye for the most fantastically appalling of possibilities. I was gripped from start to finish by the sheer scale and verve of his telling. And I’ve never looked quite the same way at a cat again.

Fantastical noir: The City and the City by China Mieville

This isn’t my favorite China Miéville (that would be the Bas-Lag trilogy), but he’s sufficiently brilliant that this isn’t saying much—and its brain-bending super-positioning of two fictional cities, Besźel and Ul Qoma, remains one of the most dazzling devices a novelist has used to explore selective blindness and the art of unseeing. A speculative thriller steeped in pitch black police procedurals, it’s not overtly interested in technology; but its meticulous dissection of hidden systems of power, and what it means to live parallel existences in the same physical space, place it among the finest fictional dissections of urban modernity.

World-renowned dystopia: The Hunger Games trilogy, by Suzanne Collins

Has any author’s vision of post-apocalyptic brutality found such a vast and admiring audience? Suzanne Collins brought into being one of the most brilliantly iconic conceits of 21st-century fiction in her creation of the Hunger Games themselves: reality television meeting classical myth as teenagers publicly fight to the death. Tech, in their ravaged and flooded future, has summarily failed to save humanity—but its totalitarian government remains glad to genetically engineer animal atrocities to liven up the theatrics.

Swiftian satire in Silicon Valley: The Circle by Dave Eggers

Dave Eggers thrills not by dreaming dystopian futures or loosing killer robots on the land, but rather by depicting an all-too-plausible parallel present. Privacy is becoming non-existent as the grateful users of tech giant The Circle’s products share and rate every moment of every minute in their lives. Privacy is Theft, declares one of the novel’s Orwellian slogans—and the snuffing out of the human spirit comes bearing not a scowl, but a solicitous grin of user-friendly ingratiation. Perhaps the most chillingly plausible tech fable I’ve ever read.

The birth of a genre: Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

Amid a genre that can often feel overwhelmingly male, it’s worth remembering that Mary Shelley kicked off speculative fiction more-or-less single handedly two centuries ago, in a work that still fascinates and chills like little else from 1818. The tale of a creature compiled from corpses and animated by electricity deserves close reading in its original form, both for its brilliance and tenderness—and for its insights into that most current of tech angsts, the responsibilities and agonies that come with creating intelligent artificial life.

***