To work with words in their hundreds and thousands in a world increasingly obsessed with brevity is not easy. Stubborn, we continue in the face of a new hierarchy of posts, tweets, tik-toks that amplify the bon-mot not the thesis. We resist despite the crushing efficiency of a brief text message of less than ten words to demonstrate that the game might be lost. And such texts usually are about loss, potential or realized. There have been many in the past two years – ‘He’s ill,’ ‘It’s bad,’ ‘She’s gone,’ ‘I’m sorry’—and we are all sorry for that. The most economic use of words to transmit immediate information, style an unnecessary companion to brutal fact.

I received such a text at the end of last year regarding an old school-friend: a handful of unexpected words that immediately launched a mental train journey, longer and more nuanced than any I could write on 500 pages. At times it threatened to run away with itself. Loss, potential or realized, is a broken mirror. Memories reflect as we reassemble the shards. The original shape is sought but handling all the pieces can sometimes be difficult. They cut. It’s best to focus on some over others.

An old school-friend gone.

Not old enough that’s for sure, but most definitely a friend of my school days, the best in fact.After our time in that remote west-country boarding school, there would be no break, no disagreement just different colleges, careers, relationships, geographies, the inevitable divergence of lives under-pinned by fond memory and the mutual laziness of assumed longevity.

Choosing a piece of mirror, I see again those Sunday lunches at his family’s home in the green countryside of Devon – they lived near and a downhill bicycle ride offered ready and rapid escape for others far from their own. Outwardly formal in the English tradition, delicious despite what you may have heard about our food, and rendered slightly anarchic by the combination of his parents charming eccentricity and our youth, we would eat, talk and laugh around the table. Good times.

Afterwards we would move to the sitting room to watch reruns of Patrick McGoohan’s The Prisoner on Channel 4 or their new-fangled video player – The Day of the Jackal, Marathon Man, Alien, Soylent Green, A Bridge Too Far, The Eiger Sanction. My friend’s father would often say, “Well if you like that, then you should read this.” The resultant proffered hardback by Forsyth, le Carré, Trevanian might have weighed down the long uphill journey back to school but that was okay. They were all great, but one of them in particular I see now had a lot to answer for when paired with the film that prompted its offer.

Shibumi (1979) was the fourth book by Trevanian, the pen name of Dr Rod Whittaker, The Eiger Sanction being a Malpaso adaptation of his first published in 1972 that was directed by and starred Clint Eastwood. Whittaker, his doctorate was in communications and film, considered the treatment of his story to be ‘vapid’ even if the film is still carried toady by the ultra-realistic climbing scenes, one of which (the ascent of the Totem Pole, a rock spire in Monument Valley) is described by Free Solo climber, Alex Honnold, as “the most realistic in all of Hollywood climbing.”

The story of Dr. Jonathan Hemlock (Whittaker, like Ian Fleming, enjoyed his novelty names) an assassin who comes out of retirement as an art professor and collector to make a kill on a Swiss mountain was part action sports thriller and part spy trope satire. Whittaker considered that the film missed the humor of his novel – an essential Trevanian ingredient – but in Eastwood’s defence the North Face of the Eiger is never a laughing matter, especially given that the fact that one of his climbing consultants was killed by rock fall on the second day of filming. A number of shots in the movie clearly demonstrate a level of commitment of crew and cast that was anything but vapid, none more so than the helicopter pan-back of Eastwood and George Kennedy sharing a beer on a sandstone table-top four hundred feet above the Arizona desert or East wood’s final rope cut, a scene worthy of Joe Simpson’s Touching the Void.

I admire The Eiger Sanction both as a reader and a climber. When I wrote Summit, my own historical fiction/adventure story about Mount Everest, it loomed large in my inspiration and also, it has to be said, intention. As a writer though it was that Sunday lunch copy of Shibumi that lit a very slow ‘one day I’ll write something like this’ fire. Humor me! Described by Whittaker as a ‘meta-spy’ novel, the story of Nicholai Hel makes stylish back-story king in the telling of the journey the multi–talented assassin takes from a complex youth in Japan to a philosophical retirement in the Pyrenees that is violently interrupted by the arrival of past demons; shibui meets shit-show. Elegantly written, also humorous, and so dense in style and source that Don Winslow could later mine it for an equally rich prequel called Satori, it ticked for me what at the time it was handed to me what were nascent boxes of fascination: 20th century history, diverse geography – European and Asian, practices and philosophies, the knowledge and skill of complex games and sports, and ultimately just travel, action and adventure.

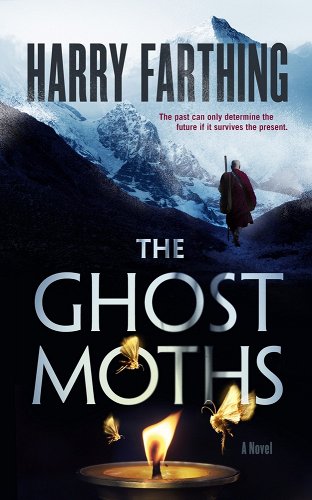

Climbing didn’t make it forward from the pages of The Eiger Sanction, this time it was the sister sport of spelunking – preferred by Hel as more ‘manly’ than mountaineering – another post-production dig by Whittaker perhaps. But all the same, vertigo or claustrophobia, choose your skin-crawler and Trevanian ensures the rope-work is as correct as the story is exciting, satirical, philosophical and, ultimately, educational. Even Winslow confesses to have poorly learned the infinitely complex Japanese game of ‘Go’ because of Shibumi. Rod Whittaker sought a screen-writing credit for The Eiger Sanction in his own name long before he revealed it to anyone else in his publications but would then equally deny the possibility of any similar movie treatment for Shibumi. As an author he embraced both mystery and eclecticism in his work to the extent that some said Trevanian was actually a writers’ collective, others that it was Robert Ludlum in disguise. Crown Publishing hyped The Eiger Sanction as written by a European who was an accomplished mountain climber. Not true of course even if Shibumi may have to some small degree helped create one. In writing my second novel, The Ghost Moths, I mined my experience and knowledge of climbing in the Himalaya, of metaphysical Buddhism and the Japanese ascetic mountain culture of the Yamabushi, and the current and past struggles of Tibet to create a story that has action, adventure and possibly even a little humor. Looking back in those shards of mirror I can now see why I believe in such ingredients and who, ultimately, I have to thank.

Goodbye, old friend.

***