True crime is having a moment. But then, one could say true crime has been having a moment for more than three centuries, since the New England–based minister Cotton Mather published his execution sermons for eager Puritan audiences, then, with an altogether different pamphlet, laid the groundwork for the Salem Witch Trials in 1692.

Lately, it’s felt different. More highbrow. More participatory. More investigative. More in the public interest. More reflective, critical, even postmodern. The current state of the genre has broadened far past stories once reliably contained within the pages of mass-market paperbacks, covers with dripping fonts. Or tabloid-friendly tales slickly packaged into programs that air on Investigation Discovery, Oxygen, and Lifetime.

The new true crime moment dates to the fall of 2014, when the radio program This American Life presented the first series of its podcast spinoff Serial. Sarah Koenig’s week-by-week account of the 1999 murder of Hae Min Lee, the incarceration of Adnan Syed, and why his conviction could have been a wrongful one, was not just a hit, but a bona fide cultural phenomenon. Everyone who was anyone listened to Serial, even if they had never consumed—or knew they were consuming—true crime before then.

Serial’s astonishing success paved the way for even stronger, more superbly reported podcasts, such as In the Dark, Bear Brook (where victim and perpetrator identification led to the burgeoning field of forensic genealogy for cold cases), Bundyville, and S-Town. Television and streaming documentaries like The Jinx and Making a Murderer expanded the storytelling range so our appetites could handle the epic, Oscar-winning O.J.: Made in America. And the state of policing and criminal justice, then and now, yielded outstanding recent books like Ghettoside by Jill Leovy, They Can’t Kill Us All by Wesley Lowery, Killers of the Flower Moon by David Grann, and American Prison by Shane Bauer.

The fascination with murder and illegality is a perennial one, because the shock of the deed creates a schism between order and chaos. We wish for justice, but even when we get it, the result rings somewhat hollow. We gorge on facts and innuendo but are then left with the hangover of trauma, the aftermath of a system that too often fails people. We crave a narrative that restores righteousness but are left with scraps of barely connected meaning.

The last few years of true crime storytelling dwells on the messiness. One important strand, as coined by WNYC’s On the Media in 2017, is “true innocence,” where convictions yield questions and possible exoneration. It’s less who did it than why did she falsely confess, or what mistakes did the prosecutor or detective or lab technician make? Season two of In the Dark, the landmark podcast from American Public Media hosted by Madeleine Baran, uncovered so many inconsistencies in the case of Curtis Flowers, tried six times for an early-1990s quadruple murder in Winona, Mississippi, that its reporting helped lead the Supreme Court to reverse Flowers’s most recent conviction.

The genre is also much more interactive. The proliferation of podcasts in particular creates communities of would-be amateur sleuths with a vested interest in seeing their pet cold (and not-so-cold) cases solved. Those communities are also spaces for finding friendship and comfort among those who love true crime, as the “Murderinos” who listen avidly to Georgia Hardstark and Karen Kilgariff’s hit comedy podcast My Favorite Murder can attest.

Michelle McNamara’s I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, her posthumous 2018 blend of crime reporting and memoir on the Golden State Killer case, was as much a paean to the web of internet users equally invested in uncovering the killer’s identity. That forensic genealogy—itself a discipline spearheaded by amateurs, working outside law enforcement—brought about the identification and arrest of Joseph DeAngelo in April 2018, is as much a testament to nontraditional methods leading to the resolution of long-dormant cases.

That sense of interactivity helps explain the recent and parallel rise of the true-crime memoir. Those who have been directly affected by crime are giving voice to their own experiences in beautifully crafted works. Beautifully crafted, well-reported literary nonfiction such as Down City by Leah Carroll, You All Grow Up and Leave Me by Piper Weiss, The Hot One by Carolyn Murnick, and After the Eclipse by Sarah Perry, as well as podcasts like The Ballad of Billy Balls by iO Tillett Wright, illuminate how the violent death of a loved one causes lifelong ramifications that don’t stop with the finished, produced work.

As I wrote for the Guardian in 2016: “a book or a documentary or a podcast is now seen as the continuation, even the beginning, of a crime story, not the end.” Internet sleuths hold themselves up as better than professional detectives, and sometimes they prove to be right. The dichotomy of true crime is not about high versus low culture, but is between observer and participant. It’s no longer enough to be horrified or morally outraged. Now, it seems, the perennial fascination that is murder has the power to make us act, even if our actions are futile.

* * *

If true crime is having a moment, how best to chronicle that moment? I am a creator and consumer of true crime. I’ve published true crime features and essays critiquing the genre. My own book, The Real Lolita, is a hybrid of crime investigation and literary criticism. I haven’t read every single book, watched every documentary, or listened to every podcast—that would, quite simply, be impossible—but in our post-Serial world, it has been breathtaking to watch this genre I’ve loved my whole life grow and change, bend back upon itself, open itself up for serious criticism, and accept the possibility that its constraints can be crested.

The time seemed ripe for an anthology of recent writing about true crime across the broadest possible spectrum. Some years ago, there were annual anthologies under the banner of The Best American Crime Reporting, collections that affirmed to me that many of my favorite nonfiction writers journeyed into the land of crime and often stayed there for good. But in the years since those anthologies ceased to be, a new and fresh crop of crime writers have arrived.

They centered the victims as human beings rather than rely on the trope of beautiful white dead girls. They widened the storytelling lens far beyond the individual to the collective. They explored different subcultures and communities. They paid attention to stark topics like inequality, poverty, housing, and addiction, all of which affect and are affected by crime. They were women and people of color. They were unafraid to call out the problems inherent to what I think of as the “true crime industrial complex,” which turns crime and murder into entertainment for the masses.

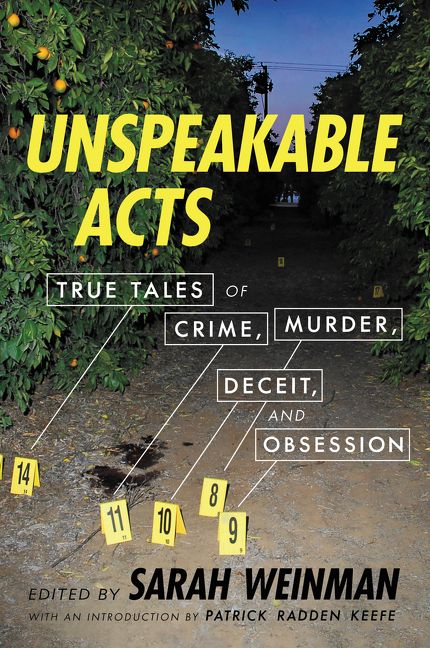

They are the present, and the future, of this genre. Unspeakable Acts includes a baker’s dozen of these writers, separated into three broad categories.

The first section highlights more classic crime features. Pamela Colloff, indisputably among the great nonfiction crime writers of the twenty-first century, is here with one of her final features for Texas Monthly, where she worked for nearly two decades. Michelle Dean’s BuzzFeed feature, the basis for the Hulu series The Act (which Dean co-created), is here in print for the very first time. Rachel Monroe, author of the standout book of true crime criticism Savage Appetites, is here with a con artist tale that reflects, and stands apart from, the plethora of pieces on grifters, scammers, and frauds. And Canadian journalist Karen K. Ho blends personal history and dogged reporting with her stellar story on a girl expected to excel, with catastrophic results.

Section two gets more meta, looking at how true crime interacts with culture as well as itself. Author and documentary filmmaker Alex Mar compares and contrasts two stories of fatal girlhood friendship—one from the 1950s, one from a few years ago—and finds eerie parallels. Sarah Marshall, cohost of the wonderful You’re Wrong About podcast, traces America’s obsession with serial killer Ted Bundy and finds him, and us, profoundly wanting. Alice Bolin, author of the indispensable essay collection Dead Girls, takes direct aim at why we’re in this true crime moment, and what it erases. Elon Green digs for the heartbreaking stories behind a legendary music video’s photo montage of missing children. And my own contribution to the anthology is on the ill-fated bank robbery, and the fascinating woman involved in it, that inspired Barbara Loden’s cult feminist film Wanda.

The third and final section widens the scope to broader issues of criminal justice and society. Jason Fagone embeds with a Philadelphia emergency room doctor who is fed up at the number of shootings and the devastating human toll of gun violence. Emma Copley Eisenberg, author of The Third Rainbow Girl, introduces us to a black transgender teenager named Sage Smith, and how her murder, and the neglect in solving the case, rippled across a town. Finally, Leora Smith introduces us to Herbert MacDonell, the so-called father of blood spatter analysis, and how his methods inspired all manner of junk science in the courtroom.

Consuming and creating true crime is an ethically thorny endeavor, as it always was, and as it must be. But the pieces included in Unspeakable Acts go a long way to make the world a more just, more empathetic place.

*