Catharine Read Arnold Williams was a fearless woman. Her multi-layered skirt firmly in hand, she gingerly stepped over ground littered with broken maple limbs before coming to a stop and gazing down at the green, well-trodden grass. Hoofprints marked various spots where cattle had grazed. I hovered nearby, settling beneath a towering maple tree. It seemed surreal as we both stood where a young woman, gifted with ability and loyalty, had lost her life. We stayed hushed for a bit, out of respect for Sarah Maria Cornell.

The tiny lines on Catharine’s alabaster skin around her eyes deepened when she expressed concern. We were the same age, but my freckles revealed years of sun damage from working on my father’s farm in Texas as a teen. Catharine, on the other hand, had never done a bit of manual labor in her life—though her wrinkles seemed perhaps more pronounced than mine, her worries etched deeply on her face. Our lives were an illustration of extreme contrast, but our divergent experiences had led each of us to similar writing careers propelled by diligence and necessity.

Catharine’s life up to that point had not been easy. The 46-year-old had contended with an abusive marriage and a humiliating divorce, before settling into life in New England as a single mother. Through it all, Catharine had nurtured a writing career that she cherished, penning a short list of novels, poetry, and biographies that braided religion with history. Despite almost immediate professional success, Catharine tended to be an impatient wordsmith who fretted over financial stability and never seemed content with her creative output or the resulting earnings.

I understood that concern. As the main breadwinner of my own home and the mother of two young children, I was also continually on the lookout for the next opportunity, the next assignment, the next book. Authoring is a tricky craft, one that feels risky even at the best of times and positively precarious during uncertain economic moments – when recessions loom, pandemics rage, and politics threaten to upend our social structure.

Aside from all that, writing is horribly tedious. I’ve often compared the art of narrative writing to the act of conscripted self-reflection. Yet Catharine claimed it was mediative for her – as I said, we had varied experiences despite our similarities.

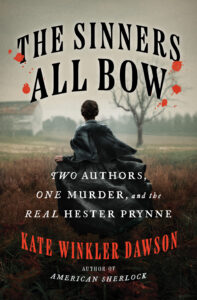

Writing a book with another person can be tormenting, melding two voices, two sets of observations, two life experiences into a single narrative. That was certainly my experience working on this book, The Sinners All Bow, with Catharine. Each of us saw things the other did not, and while our observations lined up perfectly much of the time, on occasion we each had to contend with the occasional blind spot or different interpretation of the same event. Still, I think the sum of our work together is greater than its individual parts. The collaboration process can be strenuous, but the fruit born can also be satisfying.

As Catharine and I wandered beneath the graceful branches of the magnificent maple tree that summer, we surveyed the precise spot where the victim exhaled her final breath. In most documents, our protagonist, Sarah Maria Cornell, is referred to as “Sarah,” even though she signed her personal letters with a variety of names over the years, including “Maria” and “Sally.” Catharine and I call her “Sarah” in our pages. Another quick note: Sarah was discovered on a farm in what was Tiverton, Rhode Island, about 50 miles south of Boston. About 30 years later, that part of Tiverton would be renamed, “Fall River, Massachusetts.” During the time of our story, the farm was less than two miles from what was then Fall River. It can be confusing because the cities become conflated by many writers.

Sarah’s story held many mysteries for two avid true-crime writers like us. Standing on that same field where she had walked years ago, Catharine and I could almost see her before us. When Sarah herself had slowly navigated through the dark December night, it had been deep into a cold New England winter, just below freezing. She had wandered across Fall River without the assistance of streetlights—only starlight and moonlight. Catharine and I braced ourselves against the imagined western wind that rushed across Mount Hope Bay, which was just a few yards away down a gentle slope. Sarah must have felt chilled as she made what would become her final walk—the dead grass crunching under her boots, the wind swooping beneath her cloak and seeping into her bones with every step.

My co-author and I were standing at the location of a tragedy that had perplexed and shocked the residents of nearby Fall River for more than two centuries. As nonfiction authors, it was critical that Catharine and I make the trip. We needed to see the site of this tragedy firsthand. We both noted our impressions of the area, initial thoughts that would—we hoped—eventually translate into spirited, visceral descriptions on the page. We knew how to tell a story, yes. But we also were reporters who believed in telling the truth and retrieving all the facts. These were facts, we would soon learn, that could be interpreted many ways, by those with many different agendas.

In the years ahead, Catharine and I would carefully evaluate the clues to a maddening mystery—why was Sarah Maria Cornell, a 30-year-old woman with seemingly so much to live for, found dead on this spot on a crisp December morning? Catharine and I would scour the scores of original, unpublished documents, mining for clues in the extensive testimonies of people who sought to protect Sarah. We also had to consider the damning narratives from those determined to condemn her. Catharine and I would interview Sarah’s family and her close friends – though, admittedly, Catharine was granted greater access than I (luckily for us). We would soon visit Sarah’s humble gravesite, the spot where she was finally able to rest in peace after being buried three times in two different locations.

Ultimately, we hoped that The Sinners All Bow would serve as a lesson in criminal investigation. There was discussion about victimology, motives, witnesses, criminal profiling, physical clues, and legal arguments. We both had our own forensic experts, though my list was more extensive. Catharine’s side of the investigation had its weaknesses; she refused to interview the suspected killer’s family, much to my dismay. But I did.

And Catharine didn’t realize it, but once I detected her biases, I began investigating her. What were Catharine Williams’s true intentions for writing a book about a murder that might not have been a murder at all? I secretly spoke to Catharine’s own family, to evaluate her motives and delve into her personal history.

But the focus of our narrative was the distraught young woman found dead on a remote farm one winter morning. Regardless of the cause of Sarah’s death, Catharine and I both wanted to answer why it happened. Together, we would investigate a sad, pitiful end to a troubled life; we would dissect the dynamic of Sarah’s family that led her to that bleak spot; we would study her past paramours, as well as scrutinize several sexual predators who crossed paths with her. We would examine the overt, odious assertions about Sarah’s so-called promiscuity as a cause, even a justification, for her death. Catharine and I noted the misogyny that has always pervaded America, the enduring impulse to excuse a man’s behavior at the cost of his victim. Our aim was to offer a true crime narrative that might reshape how Americans regarded the demise of a flawed, victimized woman…and how our society exploited her, even after death.

While Sarah Cornell’s story has largely been forgotten, its legacy remains. Echoes of her narrative – which was as omnipresent and infamous in its time as stories of women like Nicole Brown Simpson and Gabby Petito are in ours – made their way into all aspects of society upon her death. In fact, the details of Sarah’s story inspired one author to write one of the most important novels in American history, a reimagining of the exploitation of women. But more on that later.

True crime, I believe, is overdue for a broad reckoning. For every authentic, empathetic professional in the genre, there is an endless supply of seemingly callous true crime creators whose work exploits a victim’s past, re-traumatizing and re-victimizing their families (and the victim’s reputation) in the process. The genre seems to be at an inflection point, a moment that demands self-evaluation for all of us who venture into true crime storytelling.

Catharine Williams and I want to do things differently. We aim to offer readers a victim-centered reclamation of the “wanton woman” in the true crime narrative. As a crime historian, working with a gifted, galvanized writer like Catharine Williams was a blessing. Alongside Catharine, I wasn’t alone in my determination that true crime could help restore the public character of victims who suffered harm not only at the hands of perpetrators, but at the pens of writers who recounted their stories. That impulse is at the heart of The Sinners All Bow.

I consider Catharine Williams my coauthor, and she and I were determined to get to the heart of the mystery of Sarah Cornell’s death. The only catch: we were working on the same case almost two centuries apart. Sarah Cornell was found dangling by her neck from a haystack pole in Fall River, Massachusetts, in the year 1832. Catharine Williams began her investigation the following spring.

What’s singular about The Sinners All Bow is that my co-author has been dead for more than 150 years.

* * *

These are the basic facts of the case:

On a frigid day in December 1832, the body of a young woman was found hanging at a Tiverton, Rhode Island farm. She was identified as Sarah Maria Cornell, a worker in a nearby textile factory. Evidence implicated Methodist minister Ephraim Avery, a married man and father of four. The community was outraged that a man of God had apparently seduced and murdered an innocent mill girl.

But as more evidence emerged, this picture grew murkier, more complex. If she had been murdered, was someone other than the minister responsible? Could Sarah Cornell have planted evidence against Avery before taking her own life? Who was Sarah Cornell, really? Was she truly a victim, as many would paint her – or did she have secrets and an agenda of her own?

Sarah’s story resonated with Catharine Read Williams, who went on to write America’s first widely read true crime book, Fall River: An Authentic Narrative, in 1833. Most true crime afficionados (me included) have long believed that Edmund Pearson’s 1924 Studies in Murder was the first true crime narrative in the United States, but that’s not the case. True crime narrative had its origins within the pages Catharine Williams’s book.

Fall River was “written to convict a murderer in the court of public opinion and published as an ‘Authentic Narrative’ in 1833 as perhaps the first extensive ‘true crime’ narrative in the United States,” writes Shirley Samuels in Reading the American Novel 1780 – 1865. Catharine Williams, a poet who never intended to be a reporter, had made true crime history.

With her pious character and adherence to strict social norms of puritan New England, Catharine seemed an unlikely colleague for me. But her book was an outstanding, deeply investigated narrative of a death that outraged a country.

Catharine penned more than 200 pages in Fall River with the aim of dismantling Reverend Ephraim Avery’s defense. Catharine was, I believe, also the first author-advocate for the crime victim, which is an unusual perspective for a true crime author, even today. Her point of view was unflappable: she labeled Avery as the sinner and Cornell, while certainly not a saint, as the imperfect woman who had been victimized by her spiritual guide. He had exploited her recent indoctrination to the church to gain control of her. In contrast to the crass, big-city newspaper articles in which female victims often got what they deserved, Catharine offered Sarah Cornell some crucial sympathy—and in doing so shifted public opinion.

But did Catharine get the facts of the case right all those years ago? Fall River is remarkable in its ability to synthesize a compelling story with accurate details of the crime, social context, and impeccable reporting, like any true crime story should. But in The Sinners All Bow, I’ll reexamine Sarah Cornell’s death using the tools of a twenty-first century journalist; I’ll evaluate Catharine’s evidence and weigh whether her clear biases against Reverend Avery and the Methodists affected her judgement in this case.

The story of Sarah Cornell’s death inspired another author in his quest to craft a scathing social commentary. Several scholars believe that Sarah was Nathaniel Hawthorne’s inspiration for Hester Prynne in The Scarlet Letter, among literature’s most tragic fallen women. Six years after Sarah’s death, Hawthorne referred to the case in his journals after he toured the scene of the murder depicted in a wax display in Boston, which was a popular tourist destination in the 1800s. “July 13th—A show of wax-figures, consisting almost wholly of murderers and their victims,” wrote Hawthorne in 1838. “E. K. Avery and Cornell—the former a figure in black, leaning on the back of a chair, in the attitude of a clergyman about to pray; an ugly devil, said to be a good likeness.” Being featured in a wax museum indicated that the person had achieved a certain level of fame or notoriety or infamy. And indeed, the story of the minister and the mill girl gripped the nation. Hawthorne would have certainly known the details of the case—he was an avid reader of popular newspapers. He son, Julian, even called it a “pathetic craving,” he was so consumed by news. Hawthorne even used copy in some of his own writing.

The Scarlet Letter was published 18 years after Sarah Cornell’s death. Within its pages, Hawthorne unraveled the tragedy of a needleworker in Puritan New England, Hester Prynne. When her adulterous affair was revealed, Hester was forced to wear a scarlet letter “A” as public punishment while raising her daughter, Pearl, and being pursued by her wrathful husband. Hawthorne’s work has endured for almost two centuries as an illustration of both penance and perseverance with shades of disdain for the Puritan beliefs of intolerance and public punishment. Once you learn the contours of Sarah’s story, the parallels are hard to ignore.

Both Hester and Sarah were seamstresses embracing sexual independence, and these autonomous women frightened provincial New England. Their society had been a patriarchy that leveled punitive shame on those who unmoored themselves from a husband. And yet, both Sarah and Hester selflessly shared their gifts, despite the public ridicule that sometimes followed.

“Hester’s needlework also enables her to practice charity, for which she, like Cornell, eventually becomes known,” wrote Kristin Boudreau, professor of English and the head of the Department of Humanities and Arts at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in England. She wrote a paper called “The Scarlet Letter and the 1833 Murder Trial of the Reverend Ephraim Avery,” detailing how Hawthorne drew inspiration for his fabled character by examining the life of Sarah Maria Cornell. “Indeed, whatever their sexual transgressions, both women significantly rehabilitate their characters by performing benevolent acts with apparent humility.” We’ll see the parallels between Hester Prynne and Sarah Cornell drawn throughout this book.

“Nathaniel Hawthorne’s greatest novel owes its inspiration in part to this public discussion of seduction and murder,” wrote Boudreau, “Hawthorne’s novel is less concerned with Hester’s actual crime…than with the people’s response to that crime.”

The people’s response to Cornell’s death is the issue in our case: was the minister guilty of murder? Or of unwarranted public judgement?

* * *

The Sinners All Bow also draws on hundreds of pages of unpublished material. There are more than a dozen contemporary accounts of the case, including letters from family and friends, investigators, and notes from the prosecutor. There are also letters between Sarah Cornell and Ephraim Avery, offering an inside look at their tortured relationship. Sidney Rider’s biographical essay about Catharine Williams included her own memoir, in which she detailed her struggle as a single mother and an emerging writer in a male-dominated field.

Catharine Williams and Sarah Cornell were confined by the still-powerful vestiges of their Puritan society: propriety, devotion to the church, the commitment to marriage…but Catharine was able to disentangle a few of those knots. Catharine dared to divorce a man from a respectable family in New England, an affront to the traditional norms of the times. She persevered and eventually gained a level of respect offered to few women in New England in the early nineteenth century. Both Catharine and Sarah made a choice for independence, despite the consequences. Sarah Cornell dared to gain autonomy through mill work, and she refused to settle with a husband and raise a family; she had been devoted to a church which seemed to contradict the restrained roles of women that much of America subscribed to.

Together, Catharine Williams and I will rewrite the tale of Sarah Cornell and Reverend Ephraim Avery—and this version, drawing on the conventions and fact-checking of twenty-first century crime reporting, will present the reader with all the facts, no matter the conclusion. It will serve as a reckoning for all true crime writers: how to avoid the mistakes of the past and how to move forward by respecting the victim, no matter their background.

Catharine Williams crafted a new genre: a victim-centric, story-driven, fact-checked narrative meant to bewitch an audience and shift their belief system about women and their burgeoning independence. She believed that women could protect each other—and she demonstrated that in her own life because, after her marriage, she shunned all dependance on men. A narrative focused primarily on the victim was unique—and her commitment to thorough reporting was exceptional.

But Catharine’s own troubling history with men along with her rigid religious ideology posed a problem for our project because those factors might have influenced her judgement; this was a narrative she had framed as “authentic,” starting with the title. But Catharine Williams despised one of the central characters—the vitriol she had reserved for Reverend Ephraim Avery littered the pages of Fall River. She viewed him as little more than a craven predator, a greedy, venal man stalking the young women of New England, a brute who was only halted because of his connection to Sarah’s death. He murdered Sarah, she declared in her pages.

Catharine refused to investigate alternate theories, but a journalist who offers readers a nonfiction narrative must examine all sides of the investigation and a controversial story demands a responsible, unbiased pen. I will offer that pledge to my readers and my listeners: if you trust me, I will do my best to provide you with the full story in this case, no matter the outcome. Did Sarah Cornell die by her own hand or was she victim of a killer? And if she had been murdered…who was the killer? Catharine Williams was stubbornly, foolishly steadfast in her conclusion, well before all the available evidence was submitted. But I’ve offered a more complete picture of one of the most important cases in American history…that you’ve likely never heard of. Would Catharine and I arrive at the same conclusion?

___________________________________