The unreliable narrator: You can’t trust them but, as the reader, you often don’t have a choice. They steer the narrative and authors love to give them the proverbial keys, allowing them to exhibit any number of inconsistencies and redeeming character flaws. It’s an ingredient that often makes for a great detective or thriller novel. Just look at Fight Club and Gone Girl. What often gets hidden behind the intensity of the narrator is how the unreliability can make for surprising and unique narrative storytelling. Using a narrator that doesn’t stick to any preexisting rules makes for structural experimentation that changes the very way a story can be told. Let us take a look at some books that bend and buckle at their structural seams based on the tenuousness of its narrator.

I’m Thinking of Ending Things by Iain Reid

Iain Reid’s debut novel came to me at the right time. I remember getting a galley from Scout Press, an attractive marketing package complete with the tagline, “You will be scared. But you won’t know why.” They really nailed it on that one. The novel begins with a couple on a roadtrip on the cusp of a winter storm. The girlfriend has already made a pivotal decision about their relationship, and then after an unexpected turn, she is left stranded at a seemingly deserted high school. You go in knowing something is off, and within a few pages, you begin to doubt the narrator’s hold on not only their sanity but also the narrative itself. And then it just keeps getting weirder. Reid pulled off quite a narrative magic trick utilizing the power of a truly unreliable narrator.

The Marbled Swarm by Dennis Cooper

Dennis Cooper is a literary shapeshifter, every new book of his tackling an entirely new set of challenges. In 2011, Harper Perennial put out what is still one of Cooper’s oddest novels, The Marbled Swarm. Here’s a book whose narrator and narrative were designed to haunt, push back on the reader, and morph before their very eyes. The mystery central to the narrative is the eponymous “marbled swarm,” a language passed down from father to son that seduces and destroys. The main character is about as unreliable and narratively cataclysmic as you can get: he calls himself an unusual predator and through increasingly arcane and complex sentences, truly unexpected dead-ends and narrative shifts and changes, we watch as Cooper performs a sort of haunting that gets as close to “cursed language” I’ve ever seen.

“Love is the Plan the Plan Is Death,” from the collection, Her Smoke Rose Up Forever, by James Tiptree Jr.

Though I’d argue that much of her fiction qualifies, it’s “Love is the Plan the Plan is Death” from the only collection ever published, Her Smoke Rose Up Forever, is a timeless example of the narrator and narrative working in tandem to change the way a story is told. In this case, the story involves an alien child, who is intelligent and self-aware, resisting the urge to react and follow his instincts. He learns about what he’s supposed to be doing while the reader does, and in doing so, the story reveals the underlying horror. Since our narrator is in the dark on what’s happening much like the reader is, the language and character actions drive the narrative into surprising turns. At the time of its original publication (1973), the narrative was a first of its kind. Nowadays it’s a must-read and much-coveted example of the unreliable narrator turned unreliable narrative.

Darling Rose Gold by Stephanie Wrobel

The debut novel from author Stephanie Wrobel takes on a sensitive subject, munchausen syndrome by proxy (or when the carer for a child fakes, fabricates, and/or induces symptoms upon their child to make them sick). For 18 years, Rose Gold Watts was told she was sick—allergic to everything, basically bedridden and neutralized from a normal life. Patty Watts, her mother, it turns out is an expert liar. The novel begins where most narratives of the sort end, with the reveal, and transports the reader in the aftermath, alongside mother and daughter, two unreliable narrators, whose past bubbles up in unexpected narrative turns.

The Vegetarian by Han Kang

Everything about this book defied conventions, and it’s for that reason that it enters this list. Instead of an unreliable narrator, we have a main character who never gets to tell her story. The narrative mutes her voice, instead we get the inherently judgmental and skewed perspectives of her abusive husband, her creepy brother-in-law, and older sister. Each narrator is providing a believable account, and in doing so, the novel becomes a masterful exploration of the horrors of erasure—from identity, from self, from society. Taken in full, the narrative provides a palpable yet wholly unique breed of horror, the sort that renders you speechless and searching for a narrative of your very own.

300,000,000 by Blake Butler

Blake Butler knows how to take narrative conventions and warp them like clay. I could have picked from a few of his other books, but it’s 300,000,000 that acts as a prime example of Butler taking the unreliable narrator trope and using it to a grandiose effect. Here we are treated to two shifting protagonists, E. N. Flood, a police detective tasked with making sense of a serial killer’s pathos and mind, and the serial killer himself, Gretch Gravey. Butler was initially inspired by Roberto Bolano’s 2666, not necessarily the book itself but rather the book Butler had thought it was, prior to reading it; the result was 300,000,000, a narrative that is as much a third unreliable narrator as it is a canvas of insanity.

Tears of the Truffle-Pig by Fernando A. Flores

You could say Fernando A. Flores’s Tears of the Truffle-Pig is a fever dream but doing so would be a disservice. The novel charts narrative territory that might intimidate other writers, where drugs are everyday, legal, and filtered animals are the new tradable commodity. Flores manages to move narrative mountains while equipped with the peyote imbibing Esteban Bellacosa, who is strung along by a crazy journalist into a dizzying narrative that is as complex as its narrator is strung out. The novel demonstrates how the hallucinatory doesn’t necessarily have to be incomprehensible, and when the narrator is drugged-out, you better believe the narrative’s about to take a new turn.

You Should Have Left by Daniel Kehlmann

At first, Kehlmann’s spare novella of a book comes off as a diary of a madman. You could say that it is, but as it grows on you, with each page turned, you begin to see what’s happening. Everything that happens is in the white space, the margins, the unstated moments of the book. At its core, You Should Have Left is about a writer trying to complete a screenplay while on vacation with his family in the mountains, in a house that starts to resembles his failures. The book constantly uses spare language to indicate hesitation and silence, and the narrative in this case works directly with the unreliable narrator’s choice to tell or lie. It’s only when the narrative switches places with the narrator that the reader experiences the full spectrum of Kehlmann’s deft play.

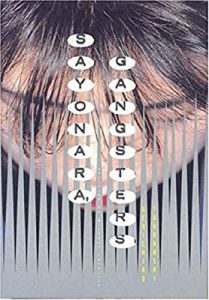

Sayonara, Gangsters by Genichiro Takahashi

The lone English translation, Sayonara, Gangsters is Genichiro Takahashi demonstrating his outwardly playful nature—with plot, with character, with narrative. The novel takes place in a near-future that resembles perhaps too much of our present, where our main character and narrator, a poetry teacher, encounters the gangsters, a terrorist group that changes the very way our main character associates with language, much less himself. The book is semi-autobiographical, a response to his time in prison which left him incapable of reading or writing for a long time. The book responds to this deficiency, with an intense amount of space, brevity, and a narrator that begins to question language itself.