Has there ever been a literary heroine like Sherri Parlay of Miami, Florida?

A stripper in her mid-30s with a weakness for men, dogs and peppermint schnapps, she starts her story by confessing to manslaughter in the first paragraph:

“Hank was drunk and he slugged me—it wasn’t the first time—and I picked up the radio and caught him across the forehead with it. It was one of those big boom boxes with the cassette player and recorder, but I didn’t think it would kill him.”

That’s it for Hank. Released from jail, Sherri announces her determination to “get myself out of the dark bars and into the daylight.” She lands a job at a dry cleaning establishment named Miami Purity. There she meets, and begins a torrid affair with, the owner’s son, Payne.

“He was wearing the cleanest shirt I ever saw,” she explains. “Clean men. I hadn’t had many of those.”

But she soon learns that, in this case, cleanliness is next to ungodly perversion. Sherri’s story spirals downward into murder and madness, as any classic noir tale must.

When it was published in 1995, Miami Purity, Vicki Hendricks’ novel about the dark doings at Miami Purity, the dry cleaning establishment, earned rave reviews as one of the wildest depictions of criminal and carnal excess ever published. The New York Times called it “a cracked hymn to American trash culture,” while Booklist labeled it “outrageously funny, grotesque yet discordantly tender.”

Among its many fans, you can count Ken Bruen (A Galway Epiphany), who said the book was “as black as the soul of a priest with malevolence on his mind, hollow prayers on his beads.” Another is Megan Abbott (The Turnout), who praised its “audacious and subversive play with a tradition it clearly both savors and lays bare.”

Believe it or not, this scorching thriller now regarded as a classic of the noir genre began as nothing but a college class assignment. Those low stakes may be the key to its winning style.

“I really didn’t have any hope of publishing it,” Hendricks said in a recent interview. “So I started having fun with it and putting all the sex in.”

***

Hendricks, like two-thirds of all Floridians, is not from Florida. She grew up in Ohio but soon concluded it was too cold in the winter for her to stay there.

On a college spring break visit to Fort Lauderdale, she fell in love with the warmth and sunshine that Florida offered. Upon graduation, she landed a job teaching English at Broward Community College in Fort Lauderdale. Meanwhile, she pursued a master’s in fine arts at Florida International University in Miami..

The FIU campus back then was chockablock with thriller authors of the present and future. Hendricks’ instructors included James W. Hall (Bad Axe), Les Standiford (Havana Run), Lynne Barrett (who won a 1991 Edgar Award for her short story “Elvis Lives”) and John Dufresne (I Don’t Like Where This Is Going). Among her classmates: Dennis Lehane (Since We Fell) and Barbara Parker, who wrote a series of eight mysteries about a pair of Miami lawyers.

Amid that group, her teachers say she definitely stood out..

“She was fearless in what she would write,” Barrett said.

Hall offered a specific example.

“She wrote a scene for a class,” Hall recalled. When he read it aloud, he realized the scene was a little racy. “Some of the other women in the class looked absolutely flabbergasted. And when I looked over at Vicki, she had a kind of amused expression on her face.”

Hall taught a class on Thursday nights called “Writing the Novel.” One assignment required the students to produce the first third of a book manuscript. Hall encouraged the students to borrow the structure of some other novel and adapt it to their own work. That’s what he did in writing his own first thriller about the loner Thorn.

Other students took as their models such modern literary classics as Catch-22 and Lolita. Not Hendricks.

“I was really into James M. Cain,” she said. “So my book was modeled on The Postman Always Rings Twice.”

There was a practical reason for choosing that terse masterpiece, too, Hendricks said. It made her job easier than if she’d picked a longer book.

“I only needed to produce 53 pages,” she said. “I didn’t have a lot of time between teaching and taking classes.”.

Barrett, who taught a course on Cain and his work, praised her choice of a model. Although Cain wrote in a tough-guy style, he found his dramatic inspiration in opera, she explained. His mother had been an opera singer, he’d hoped to become one, and his fourth wife was one.

“Opera gives you big highs but also big lows,” she said.

Hendricks’ big innovation was switching the genders of the genre characters. The doomed male narrator, drifter Frank Chambers, became a down-on-her-luck female. The femme fatale, scheming Cora Smith, became a handsome guy.

When Hendricks turned in the assignment, Hall loved it. He showed it to Standiford, and he flipped too.

“I said, ‘Jesus Christ, this is gold! You need to finish this!’” Standiford said.

Hendricks decided to complete the manuscript and use it for her master’s thesis. She had no idea it would go further than that.

***

One of Hendricks’ own community college students had sparked her interest in dishing the dirt on a dry cleaner.

The student talked about all the odd things that dry cleaners find left behind in people’s clothes. That led to Hendricks spending a day at a real dry cleaners, doing research that enabled her to produce a realistic setting for the outlandish action.

“That’s the thing I was most struck by, her using the setting of the dry cleaners,” Barrett said. The clean versus dirty contrasts help drive the narrative, she said, “and it also turns out that there are all kinds of ways to kill someone there.”

“Purity,” though, is an unusual name for a dry cleaners. Those small businesses tend to gravitate more toward practical descriptions. Real Miami dry cleaners have names like “Fresh and Clean” and “One Stop.”

Hendricks, when asked where she’d come up with the cleaners’ unusual name said, “I think I made it up, thinking that dry cleaners are purifying your clothes.” She said she wanted the book to show a world that was “clean on top but dirty underneath, with all sorts of shady goings-ons.”

She turned in the completed manuscript to meet her degree requirements, defended her thesis and graduated with an MFA in 1992. She figured that was the end of it. Unlike some of her more boastful classmates, she had no expectation of ever seeing this particular work in print.

***

Two years passed, during which Hendricks tinkered with the manuscript but didn’t show it to any agents or publishers.

“I didn’t know where to send it and had little confidence that anyone would want it,” she recalled. “I was busy teaching, and I was going to conferences and continuing to work on it.”

Barrett, who had become a friend, encouraged her to send the manuscript to famed agent Nat Sobel because he represented some faculty members. She did and enclosed a note mentioning those other clients.

Then she headed out to a writer’s conference in California. While she was in a session, someone came by and gave her a note that said, “Your agent called and said Sonny Mehta is interested in your novel.”

Hendricks had no idea who Sonny Mehta was. The venerable president and editor in chief of A.A. Knopf was someone she’d never heard of. She read the note and told the person sitting next to her what it said.

“Oh my GOD!” the woman replied, and quickly filled her in.

Because Hendricks was on the West Coast, she got the note too late in the day to call back to the East Coast. But word spread among the conference attendees and people soon were buying her drinks to congratulate her.

Even once she returned the phone call, she failed to react the way most writers would. She was due to leave on an environmental exploration trip and had no intention of postponing the trip for a publisher.

“I was leaving for Peru,” she recalled. “I’d already paid for my ticket and I had all my gear ready. So I said, ‘Hey, how about I talk to you in a month?’”

And with that, she took off for South America.

***

Mehta, as it turned out, was willing to wait for her to return to the States. That’s how much he believed in her book. But he wondered about the first-time author.

Hall, who knew Mehta, says he got a call from the legendary editor asking about his former student.

“Sonny called and asked me two questions,” Hall recalled. “One, was she promotable. I took that to mean, Is she physically okay, is she articulate, can she stand in front of a crowd and talk about the book. I said yes, she is definitely promotable…And number two, can she do it again? They wanted her to do that kind of book over and over again.”

Hall answered yes to that one as well.

Mehta took Hendricks under his wing, signing her to a two-book deal and carefully going over the manuscript of her debut, making subtle changes.

“He was the nicest guy,” she recalled. “Every time he wanted to make a change in the manuscript, he would ask if it was OK.”

He’d also take the time to explain why the change was needed, she said. Most of the changes involved eliminating “things I was repeating when I had already implied them.”

He particularly liked books with tough female protagonists, she said, and that’s what drew him to her manuscript. He also liked the title, which she wasn’t keen on – yet.

“I took months trying to think of something more clever or meaningful,” she said. “Eventually, I had no choice, and it grew on me. The antithesis of Miami and Purity used together became obvious as an oxymoron when I started talking about the book. Now I can’t imagine anything better. As usual, it’s like I didn’t know what I was doing and got lucky.”

Mehta arranged for Miami Purity to be published by Knopf’s Pantheon imprint. When it hit stores, the reaction of some reviewers reflected that of the flabbergasted women in Standiford’s class. The headline in Hendricks’ hometown paper, the South Florida Sun-Sentinel, said, “First Novel Features Sex, Sex, More Sex.”

Mehta sent her out on tour with a veteran of shocking mysteries: James Ellroy. Ellroy had just published American Tabloid, the first novel in a series dubbed the “Underworld USA Trilogy” that Ellroy has described as a secret history of the nation in the mid-to-late 20th century.

Ellroy, too, sang the praises of her book, calling it “an instant redneck savant classic: so gruesome and deadpan outlandish that you wind up baying at the moon like a Florida coon dog.” Hendricks said while they were on the tour, he did a fine job of shielding her from the creepier male admirers she encountered.

Miami Purity helped launch a wave of neo-noir writing in America, Barrett said, “and it was definitely a leap toward having more women writing in that area.”

And then it came time for her to write her next book.

***

If anyone expected a sequel to Sherri’s dark tale, they were sorely disappointed.

Iguana Love (1999) is another first-person story of desperation. The narrator is Ramona Romano, who leaves behind her mundane life as a married but bored nurse to feed a growing obsession with thrills from scuba-diving, weightlifting and a sleazeball named Enzo.

One reviewer called her “Jim Thompson in a G-string”

She followed that up with Voluntary Madness (2000); Sky Blues (2002); and Cruel Poetry (2007) which was nominated for an Edgar. Her output led to her being dubbed “Queen of Noir,” even though each one was set in a sunny Florida locale.

“Around every tree in the Florida setting lurked a noir opportunity begging to be explored,” she said in a 2013 interview with Lee Goldberg.

Her most recent book is a collection called Florida Gothic Stories (2010). One story is about a woman who leaves her husband for a dolphin. Another features conjoined twins having their first sexual encounter.

Although all of her books have a cinematic feel, none has been made into a movie – yet.

“Miami Purity was almost always under option over the years,” she said, both as a movie and a TV show.

At one point “we had a showrunner, and she pitched it as a series to many of the existing channels at the time. Several production companies were involved and we thought surely somebody would pick it up, but nobody did.,” Hendricks said. “Right now, nobody has it optioned but people often inquire. Iguana Love is optioned at present.”

Hendricks is working on her next novel now—not another noir modeled on Cain, but one with a more gothic feel. It’s adapted from another mystery master, Edgar Allan Poe classic. She’s calling it “Chez Usher.”

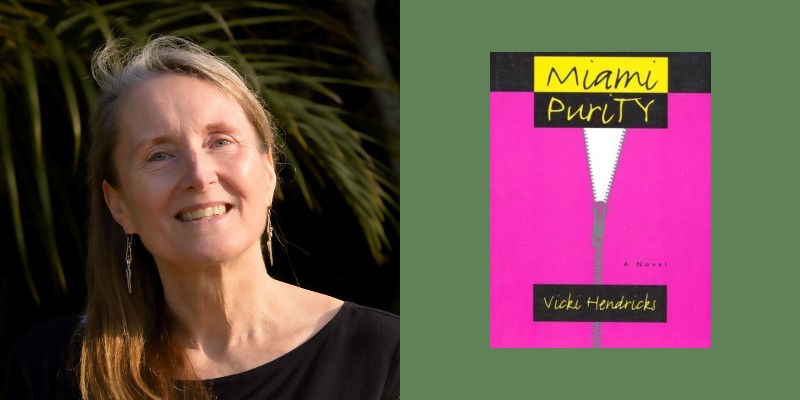

–Author photo by Garry Kravit