It should come as no surprise that Victorian mysteries tend to be Anglocentric. No other country has so embraced the genre. Victoria came to represent not a country, not an empire, but an era. One could be forgiven for thinking that all Victorian mysteries are set in England. Fortunately, such is not always the case.

Fin-de-siecle, the Gilded Age, the Meiji Era; each country has their own name for the second half of the nineteenth century, and each one had a love for mystery fiction. There are Victorian mysteries set and written in other lands, and as a keen reader of the era, I want to track them down and read them. Some are translated. Some are written in modern times. Others are written by people obsessed by the time, the place, and a juicy murder. All are worth reading.

I keep these books. They have a permanent place on my bookshelf, even though they seem as out of place beside each other as they do beside my boxed set of Sherlock Holmes stories. Track down these gems and you’ll find a world both familiar and unique. Here are five to peak your interest.

The Fencing Master, by Arturo Perez-Reverte (Harcourt Brace and Company, 1998)

Set in Madrid in 1868 during a period of great political unrest, this book concerns Don Jaime, a fencing master and man of honor in a time when such a concept was considered outmoded. He declines a request from a young woman to teach her a forbidden fencing technique, but soon she draws him into the modern world of revolution and political intrigue, where honor is considered as quaint and old fashioned as the weapon he teaches his pupils to use. Is he a dinosaur, or does what he has to teach the young woman still have worth in this “modern” century? This is a Perez-Reverte masterpiece.

The Winter Queen, by Boris Akunin (Random House, 2003)

While American youngsters and their parents stood in long lines to purchase the latest Harry Potter, Russia was experiencing something called “Erastomania.” The public could not get enough of a young police detective named Erast Fandorin as he navigated the bureaucracy and upheaval of pre-revolution Russia. A young man from a good family shoots himself in front of a crowd, and the case is shunted from one governmental department to another until it is given to the newest member of the Moscow C.I.D., police clerk Fandorin. The bureaucracy would prefer that the matter simply go away, but the young man has the brains, the charm, and the drive to see the case through to the end, managing to tick off every one of his superiors in the process.

The author is Boris Akunin, the pen name of Grigory Chkartishvili, and so far, thirteen novels in this series have been published in Russia. Interest was not as avid in the West, but translations are now available in English. If Anton Chekhov turned to writing mysteries, this is how his books would read.

The Fig Eater, by Jody Shields (Little, Brown and Company, 2000)

As a mystery writer, I find it monumentally unfair that a former Vogue editor wrote a mystery as fine as The Fig Eater. But Jody Shields, did, and the world is better for it. Set in Vienna, a detective known only to the reader as “The Inspector” investigates the death of a young girl from a bourgeois family, using the latest rationalist methods taught in Europe. After a hard day, he goes home to his wife Erszébet and tells her almost nothing about his work. In spite of this, Erszébet becomes obsessed with the dead girl found with a stomach full of figs. Co-opting an English nanny, the two women launch a parallel clandestine investigation, using different methods and understanding female motivations the Inspector would never understand.

Shields does a superb job of evoking pre-War Vienna in the days of Sigmund Freud and the suspense builds as one wonders which spouse will solve the murder first and what will happen afterward.

A Samba for Sherlock, by Jo Soares (Pantheon Books, 1997)

I have some trepidation about recommending Jo Soares’s A Samba for Sherlock (Pantheon Books, 1997). I’ve seen one reviewer call it the worst novel ever written. Tall words, that. Some Sherlockians I’ve met have compared the book to opening Conan Doyle’s grave and spitting in it. If you’re a purist, you’ll hate it. If not, give it a chance.

A Samba for Sherlock is a parody. What if Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson arrived in Rio de Janeiro circa 1886, and discover that all the hard won skills and natural abilities possessed by Holmes don’t function in Brazil. He doesn’t know the streets, he can’t speak the language, and almost everything he does fails. A serial killer murdering young prostitutes finds it ridiculously easy to outwit the Great Detective. One can see how the name of the book and its author, a well-known talk show host in South America are not spoken of among Sherlockians. Soares does a good job of describing nineteenth century Rio, a cosmopolitan city where Sarah Bernhardt is currently performing at the Opera House. If I have one criteria in choosing books, it is whether I feel I’ve learned something about the country or the city when I’m done. Sherlock Holmes is big enough to survive assaults like this work.

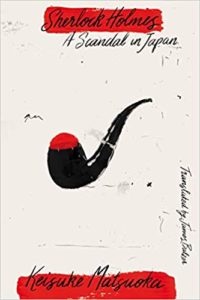

Sherlock Holmes: A Scandal in Japan, by Keisuke Matsuoka (Vertical, Inc., 2017)

Speaking of Sherlock, my last recommendation is called Sherlock Holmes: A Scandal in Japan, written by Keisuke Matsuoka. Beginning at Reichenbach, in the perspective of both Holmes and Moriarty, the surviving Holmes travels to Japan. He is in time to witness the infamous Otsu Incident, where a police officer attempted to kill Nicholas, the son of the tsar, on a state visit. This very nearly precipitated a war between the two countries, but Holmes and Japan’s first Prime Minister, Hirobumi Ito, weather the intrigues and saber rattling.

I don’t know whether to thank the translator, James Balzor, or the author himself for such fine prose. The book is well-researched and we see Holmes’s impressions of Japan and Japanese thoughts about this famously eccentric English genius. The Japanese themselves are such Holmes fans one expected something like this to be written sometime, and it is done very well.

* * *

That concludes my list so far. I hope translators are now working on historical mysteries set in Bolivia, India, or Norway. I still have a lot of Victorian countries to explore by proxy.