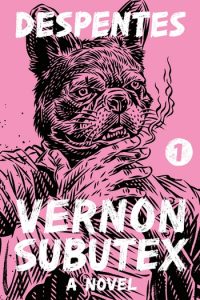

Vernon Subutex (FSG Originals) is the latest from writer and filmmaker, Virginie Despentes. Readers may be familiar most with her novel, Baise-Moi, and the film adaptation of the same name, which resulted in international attention and cult status. With Vernon Subutex, a trilogy of novels, Despentes has settled on new literary territory. Vernon Subutex is a record shop owner who is, like the rest of the industry, hit by hurdle after hurdle as music and the way it is consumed changes. With the decline of CD and vinyl in favor of digital streaming, Subutex loses his shop and, after selling all his inventory and memorabilia on eBay to stay afloat for the first years, he ends up dead-broke and homeless. That is, until word gets around that he has VHS tapes of tragically dead rock musician, Alexandre Bleach, in his possession. What happens next is a jet stream of compulsively readable transgressive prose. Despentes has managed to capture a perfect blend of the literary and crime, and in this case, the “crime” might in fact be the life itself. I spoke to Despentes about the titular character at the center of the trilogy, social media’s influence, the future of music, and more.

MICHAEL SEIDLINGER: How did you happen upon the Vernon Subutex character?

VIRGINIE DESPENTES: As I was in the early stages of writing a novel about someone my age abruptly losing her home, I read an article about Whitney Houston, who’d just passed away. There was something in the piece about her relationship with Robyn Crawford, and I got interested in the idea of a friendship between someone who becomes a star and someone left over from the star’s previous life. Vernon came out of this idea—and I immediately thought he could be a record-shop owner, because the record industry was a good emblem of the shift between the twentieth and twenty-first centuries: this enormous cruise ship that seemed nearly indestructible and yet sank in just a couple of years. Since I actually did work at an independent record shop in the late ’80s, it also occurred to me that if I imagined meeting our regular clientele thirty years later, I’d be dealing with a very wide and interesting range of people now in their fifties. Vernon grew in my mind into a paradigm of the punk rock guy who gets old while refusing to let go of his teenage spirit.

A lot of Vernon’s traits, his ways of reacting to the world, come from close friends of mine, but they also come directly from me. In our teenage years we really built our whole lives around punk, hardcore, and hip-hop cultures—and I myself oscillate between considering it all a fantastic gift or a complete catastrophe.

Subutex is unlikeable yet relatable, disgusting yet endearing. You have created a complex character that mirrors human highs and lows. What do you think of Vernon since completing the trilogy?

Another origin for Vernon was the 2008 financial crisis, which blew away a lot of traditional infrastructure in Europe. I was living in Spain at the time, and many people over sixty who lost their homes in the crisis committed spectacular forms of suicide—and there were also massive demonstrations by the elderly, which had a very strong impact on me. Here were people who’d managed all their lives to cope with paying the rent, with keeping food on their plates, with surviving—one way or another—until the crisis. And the situation also deprived the younger generations of the ability to take care of their older relatives: if you don’t have a job, there’s no money, and if there’s no money, you’re not going to be able to tell your parents to come and live with you. Vernon in my mind was kind of representative of the state of a nation where adults get old very early, the knowledge they’ve managed to gather is useless, the tools they know how to use in their society are already obsolete, and the job market has no need for “old” people. In the novel, Vernon is depressed—he’s unable to even try to fight a system that doesn’t have any use for people like him. But it would have been the same novel if he was a fighter: what I see around me is that your attitude doesn’t change much about your situation. When you’re over forty and shit happens it doesn’t matter whether you fight or not—you’re gonna sink, and that’s all. What Vernon takes from his rock ’n’ roll lifestyle is an attitude, and that’s it. And his attitude just lets him keep his sense of humor, no matter how bad things get—it makes him too relaxed to be really depressed.

If you met Vernon at a bar and listened to his stories, what would you think? What would be your response, your departing words?

In the novel Vernon has charisma—so I would talk to him with great pleasure. And I would give him money, because I have some these days. I wouldn’t give him enough to change his whole life because I don’t have that kind of money, but I would give him enough to make him feel a little relief. I think that’s what people in his situation need: money so they can breathe.

As a struggling writer/artist myself, I really related to the early chapters where Vernon coaxed his way into an increasingly narrow and financially dire situation. How did you render these chapters in such remarkable detail?

I have friends. You notice a torn-up jacket, worn not because it’s much beloved but because a new jacket is too expensive. You notice when someone is always ready for you to drop by his place or to come by yours but has lots of excuses ready to avoid meeting outside, because there might be a beer to pay for, or a pizza, or a movie ticket. You notice when it happens to someone—even if a weird sense of shame prevents them from coming right out and saying “I don’t have money and I’m not expecting to get any.” And the person might disappear, slowly, and most of the time without asking for any help, because we’re all deeply convinced that we’re responsible for a precarity that has nothing to do with the failures of our individual strategies in life—but is systemic. That was one of the bright sides of the yellow vests movement that took place last year across France: people were finally talking to each other, and so getting past that shame. Talking to each other and talking publicly they realized it wasn’t at all a question of how they personally dealt with paying their bills: when your income isn’t covering your rent and taxes the math is very simple and has nothing to do with your own sense of responsibility. You’re not poor because you’re a fool; you’re poor because your wages are smaller than your needs.

About Emilie, which is a character wise and every bit as punk as hell, truly aging-punk and/or hipster to a fault—does growing older have to feel so caustic or can it be more?

Look at Lydia Lunch. Look at Debbie Harry. Etc. They don’t look very caustic to me and it isn’t because they’re famous artists—you can be a famous artist and feel like a wreck. Emilie in the novel is like the other characters because the novel is related to what I felt when I came back to live in Paris after four years spent in Catalonia: the whole country seemed depressed to me. In Spain, the crisis immediately translated into poverty for many people, but in Paris, a lot of my close friends were still more or less wealthy and didn’t suffer economically from the crisis. But still—everybody was depressed. And that was before the terrorist attacks. So Emilie represents a specific way of aging as a former punk—year after year she lost everything that had emotional value for her, everything that made her feel special, and she lost all that was precious to her doing what she was told was “the right thing” to do. When I write about her I write about friends who tried hard to be good girls and didn’t get much in the bargain.

What do you think of social media? You utilize it so well in the novel, how word gets out about those tapes; I just couldn’t help but wonder about your feelings about social media. What do you see redeeming in it—the good, the bad, the ugly?

If the medium is the message, the most important news about social media is that it’s removed the individual’s sense of both her privacy and her distinctiveness. But I’ve read Jaron Lanier, and I followed the news about Cambridge Analytica, so my own discomfort about social media has grown a lot since I wrote Vernon Subutex. At the same time, I was amazed by what’s happened thanks to the “#MeToo” movement. I’d never witnessed an international uprising before. The Internet was a crucial game changer for feminisms, as it was no longer necessary to go through the approbation of old men’s media to spread the texts and the information. I am fifty years old, so I spent most of my life in a world where street harassment wasn’t a topic of conversation, where workplace harassment wasn’t a topic of conversation, where female bodies in public spaces weren’t a topic of conversation, where the problems of women in general weren’t interesting enough to get onto the front pages. The Internet changed that—50,000,000 voices stating the same facts from all over the world can’t be all stupid, lying cunts.

“Every work of art has to submit to the same rules as advertising: it should be consumable by the whole family, young kids included; it shouldn’t make you think or change your mind about anything, it should only comfort you, the reliable customer.”

But at the same time—social media has allowed an entire generation to grow up considering sexual censorship perfectly normal and to anonymously denounce whatever message they don’t feel comfortable with; and through social media we’ve gotten used to the idea that nothing we say should ever hurt anyone’s feelings. In just ten years, we’ve learned to look at works of art with the same expectations we bring to a tweet. Complexity isn’t an option anymore, or the idea that you might be able to address your work to a specific audience who’ll be able to decrypt it properly. Every work of art has to submit to the same rules as advertising: it should be consumable by the whole family, young kids included; it shouldn’t make you think or change your mind about anything, it should only comfort you, the reliable customer. So I would consider that culture as we once knew it has been totally appropriated and flattened by social media.

What are your favorite genres of music? What fuels your heart and makes you emotional? What do think will happen to music—is it going to be all Spotify and streaming? What are your thoughts on how music is consumed nowadays and how it might be consumed in the future?

I don’t think much about Spotify and streaming but I’m thrilled to see that music is still a powerful force. I went to a Kate Tempest concert in Paris last week and she left a crowded room screaming with enthusiasm. She’s an artist who really is changing the game—a writer and a performer; she’s giving a voice to and embodying her own words—spoken word existed before, slam existed before, poetry existed before, rap existed before, but she’s taking all that stuff altogether to a whole new level. There’s an audience ready to recognize what she does, and I feel good about that.

As I’m still visiting Barcelona a lot I was already familiar with Rosalía’s work, but the fact that she’s the one from that scene whose work spread all around the world also strikes me as good news. What she did with flamenco—how she brought it somewhere new is amazing, and—again—the fact that there’s an audience ready to recognize talent wherever it hatches strikes me as good news…

So, Alexandre Bleach, the peak example of celebrity, right on down to his cause of death. What do you think of the myth of celebrity? How society tends to undervalue a person until they die?

We tend to love dead people—because once they’re gone, we can turn them into pure objects of our desire. They can’t escape—we can do whatever we want with what they left behind. And the myth of the pure one crashing against reality and dying is something we tend to fetishize. I personally prefer my friends and intimates to stay alive—even if by staying alive they destroy the ideal image I had of them. Staying alive for as long as you can is difficult. But yes—to answer your question, it’s cool for a company to work with a dead artist, you can capitalize on everything of theirs, and you don’t have to bother with any kind of resistance.

What do you think about how people now work hard to find their “personal brand”? We’re all fighting to have some degree of “cultural capital.” What of the “personal brand”—as a term, as a concept?

“I don’t think there’s much left to hope for from my generation, though. Our capacity for imagination got lost along the way.”

We globally got kind of radically screwed in the international triumph of Chicago capitalism—I mean… it’s been raised to a level of absurdity and cruelty that wasn’t predicted in even the worst dystopias we imagined… At the same time, personal branding is not really new: in Catholic culture the mantra “the most important thing is to make believe that everything is virtuous in my life—no matter what the reality, is appearances have to be protected” has always be the bourgeoisie’s primary objective. But what’s new is that we’re so ready and willing to give everything to capitalism—how our kitchen looks, the children we’re raising, our political statements, our friends, our texts, our holidays, our hobbies—because we’ve become so scared of exclusion. Being an outsider used to be an option. It’s not anymore. Exclusion equals social death—and no sort of individuality or subversion is accepted unless it’s sponsored by a fashion brand. That sort of culture builds up nations of losers unable to fit in, and yet unable to unionize to reclaim their particularity. But, maybe, young people will figure out how to escape from this international dictatorship—maybe what we’re going through now are the last years of Chicago capitalism: it could collapse for the greater good in the blink of an eye. Who knows—it looks like humanity is condemned, but as we haven’t disappeared yet, something might still happen… I don’t think there’s much left to hope for from my generation, though. Our capacity for imagination got lost along the way.

—Author photo by JF Paga.