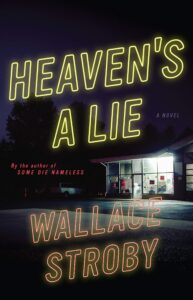

Heaven’s a Lie is the latest novel from Wallace Stroby, author of the acclaimed Crissa Stone series. Reminiscent of 1950s noir paperbacks, Heaven’s a Lie is a lean, chiseled thriller dripping with melancholy and wintry Jersey shore atmosphere. Not only among his darkest works, it’s also his most poignant. At the heart of the story is Joette, a widow and former bank teller who was laid-off and now works at a decaying, roadside motel to help support her dying mother. Her life changes when a car crashes in front of the motel, and she finds a bag full of cash in the trunk. Desperate, she takes the money, unaware that its true owner—a drug-dealer named Travis—wants it back. Badly. Heaven’s a Lie a masterfully crafted novel that reinvents a classic crime scenario and displays the hallmarks of Stroby’s prose—taut, expressive, and emotional storytelling at its finest.

On the occasion of the book’s release, I spoke with Stroby by phone about the origins of Heaven’s a Lie.

Cullen Gallagher: Heaven’s a Lie is much more intimate than your previous book, Some Die Nameless. Did you intentionally set out to write something that was such a contrast?

Wallace Stroby: Yes, I did definitely want to do something that was more intimate in scale. Some Die Nameless, especially the last third of it, is international, and there’s a lot of action, almost like James Bond-type stuff, which I really wanted to write because I love that kind of thing. But once I did that with Some Die Nameless, I had scratched that itch. I didn’t really want to write like that again. I wanted to do something that was set at the Jersey Shore in winter, and something that had to do with loss. Somebody who was struggling with loss, an opportunity presents itself, and what do they do.

CG: How much of the story did you have prepared going into Heaven’s a Lie?

WS: I didn’t really have anything planned in advance. I found it very difficult writing it. There was a lot of stuff going on in my life, my mother was very ill, and then my brother was very ill and they both passed within a year of each other. It was making concentration very difficult, but I knew I had a setup, with the accident and the money, and that set things in motion because it has to be resolved one way or another, there’s a narrative push on people. I didn’t really know where it was going to be going, and a lot of times I went in the wrong direction and backed up.

CG: Joette diverges from your other protagonists, who have included a professional thief (Crissa Stone), a journalist and a mercenary (both Some Die Nameless), a deputy sheriff (Gone ‘til November), and an ex-state trooper (the Harry Rane series). Joette’s more of a working-class everyperson. How did you choose her as your main character?

WS: When I started writing the book, I had a conversation with Josh Kendall, my editor at Mulholland Books. He mentioned that so many of my characters in the past had been alienated, and their alienation was part of what the story was, so he said I should give Joette some connections, she should be a caregiver. And then I thought, yeah, absolutely. I had been going through that situation myself and thought I can write that with some resonance so it feels real. There’s always the moment in a book where a character makes a life changing decision, and you gotta be with that character at that time. You can accept it if you feel it with the character, even if it’s a really bad decision. You have to be empathetic.

CG: When she explains her motivation as, “I guess I just got tired of people taking things away from me,” I thought that was such a powerful and relatable emotion.

WS: That idea became central to her character, but I didn’t know that when I was writing it. I was pretty far along before I realized that was really what she’d been wanting to say.

CG: The motel seems like a perfect symbol for the Joette’s transience, feeling lost in life. Was that always the setting, or did you consider any alternatives?

WS: No, I always knew it was a motel and kinda heavy handedly called it The Castaways. There used to be, in Monmouth County, a lot of mom and pop motels, not chain places, just real basic motels. There aren’t a lot of those now. People would go to them who couldn’t afford to stay closer to the beach. In the book somebody says that the motel is 15 minutes from the beach, and the cop says, try half an hour. A lot of these motels in the winter are used to house people who were either homeless or transient.

CG: Mickey Spillane once said a first line sells the book and the last line sells the next one. I loved your book’s opening: “Watching through the office window, Joette knows the BMW won’t make the curve.” Going in, did you always know that was going to be the first line?

WS: I have to give a shout out to William Boyle. I had written 30 pages, maybe, of the book in my regular third person, past tense style. And it just felt distant. It felt cold, and Joette’s not a demonstrative character. There was a distance there that I wasn’t comfortable with and I just could not make it seem to work. And then I read Boyle’s book The Lonely Witness, which has a female main character and is written in present tense. And when I saw that I thought, I’ll try that and see if that works with Heaven’s a Lie, and it did. It solved that problem because then once it’s in present tense, you’re with her, you’re seeing things as she’s seeing now, there’s no distance. But then the issue becomes how much story can you relate within her perspective? And one of the issues I had with that was the opening. I went back and forth on that line, which sounds nitpicky and crazy now, but it wasn’t at the time. I had suddenly become worried: could she really have known what make car it was in the brief instant that she saw before the accident? Because if I’m telling it through her perspective, then it’s gotta be accurate to her perspective. I went back and forth on that. It felt weird. I changed it to just a black car and then it felt too generic. And I talked it over with my editor finally, and he said, nobody’s going to care. If you break perspective very slightly, then no one’s going to notice. Whether it’s powerful or not is what’s important, and don’t nitpick it.

CG: And did you know how the story would end?

WS: No, and that was a problem. I got like three quarters of the way through it, and I didn’t know how things were going to resolve, or how dark Joette was going to go.

CG: Would you write in the present tense again?

WS: I don’t think so. It worked for Heaven’s a Lie, but for what I’ve been working on since, no. Third person, past tense works better for dealing with multiple characters.

CG: The villains in Heaven’s a Lie reminded me a bit of Elmore Leonard in the sense that they’re really vicious, but also a little physically vulnerable, and they make mistakes. What makes a good villain for you?

WS: I think a lot of my “villains,” so to speak, quotes around that, are kind of an archetype. They’re dangerous guys who are running out of road. That’s always the way I looked at it. I start off with the villain idea, and the demands on them. With Travis, he’s just a low-level guy, but he’s losing his grip, friends are turning against him, things are getting more dangerous, and then this woman out of the blue has totally fucked up his life and he’s got to try and get things back together. While he’s in descent, she’s in ascent. She’s wearing him down. There shouldn’t be any question—he’s this killer and she’s this widow that works in a motel, and how is it that she turns the tables on him? Then his character became interesting in opposition to Joette.

CG: Early on he tries to psych her out by saying, “Don’t fool yourself into thinking you’ve got choices. Because you don’t,” and yet he’s the one with no choices. She’s constantly making choices throughout. Once Joette starts realizing her own agency, then she starts really surprising him, but also us, the readers, and I think even herself a little bit.

WS: I don’t know if I thought about it that way, but I think you’re right. Josh, my editor, and I were talking about Elmore Leonard novels, actually. He raised the point of what he called “hidden muscle,” which is when a character is underestimated, and it turns out that they have this ability that they may not have known, to actually deal with this world.

CG: Cosmo, Travis’s partner, seems like a criminal who’s in it for the money but not the violence, unlike Travis who doesn’t shy away from brutality. How did you conceive their relationship?

WS: I wanted to give Travis somebody else in his life. There was a time in their relationship, years before the events of the book, where Cosmo was able to be successful in his drug dealing, because he had Travis to back him up and to chase off the people that would be wanting a piece of him. Also, you gotta have somebody for people to talk to, you know. It can’t all be interior monologue. You gotta see how people interact with people. Travis has got this affection for Cosmo, but he also knows Cosmo’s the weak link. Things are getting worse and more intense, and then Cosmo’s saying, “You know, I’m really not down with this, I’m not too comfortable with this.” For Travis, that’s something else that he’s gotta worry about. He’s got all these people that he’s screwed, people he’s ripped off, people he’s killed, this money he’s missing, all these things are piling up on him. You could look at Joettee as being the villain of the book. I mean, that is Travis’s money that she steals.

CG: In a sense, she’s a thief.

WS: It’s the idea of what you’re capable of. You don’t know until that situation happens. And then once you do make that decision, how do you go back? Can you go back? Is it a decision that was something impulsive or was it something that was waiting to come out all along, waiting for a shot? Joette doesn’t even think about it when she takes the money.

CG: Was Heaven’s a Lie always the title you had in mind?

WS: I have a yellow legal pad of titles. I always go through a situation where there is a title that somebody is not crazy about it and they want to change. It was gonna be called Dark of the Day. Then there was the question of, well, is it going to be Dark of the Day or The Dark of Day? There were a couple of covers made up, and Mulholland thought Heaven’s a Lie was problematic as a title, and it probably was. I had some alternates. One of the alternate ones was No Part of Heaven, a line from a Springsteen song called “Youngstown”: “When I die and I don’t want no part of heaven.” Then I thought that was kind of longish, and they still weren’t crazy about “heaven.” Then the photographer, Keith Hayes, who’s done a lot of George Pelecanos books, came out with that beautiful shot of the convenience store at night. The art director took it and laid that neon font over it with Heaven’s a Lie, and then everybody went crazy about it, and I saw it and I said that’s great.

CG: It’s coming up on 18 years since your debut, The Barbed-Wire Kiss. If you could go back in time, is there any advice you would give yourself before writing it?

WS: No, because I was prepped to write my first novel. I had been doing a lot of interviews with writers that I admired for publications, either the paper I worked at, or Writer’s Digest, in the ‘90s. I interviewed Stephen King a couple of times, Clive Barker, James Lee Burke, Gerald Petievich.

CG: Was there any advice that stands out?

WS: Gerald Petievich and I had kept in touch. At one point, I was offered a job at the Star Ledger, which was five times bigger that than the paper I was working at, the Asbury Park Press. I had started a novel and for the first time I was picking up some traction when I got this job offer, which was an hour away. I knew the job was going to be more work than I had ever done before. I didn’t know what to do, whether I should turn the job down and try and concentrate on the book, or take the job and then maybe he never finish the book. So, I messaged him and said, I can’t make a decision, what do you think? He immediately said take the job, it’s going to greatly expand the circle of people you know, and he was absolutely right. He said, it’ll be rough at first to try and work the writing into your new duties, your commute and everything, but eventually you will do that, you will work it in. So, I took the job at the Ledger and became friends with a writer named Mark McGarrity, who wrote a series of crime novel set in Ireland under the name Bartholomew Gill. At that time, my agent was Knox Burger, a legendary New York agent who had represented Donald Westlake, Martin Cruz Smith, and Lawrence Block, and had been the editor at Fawcett Gold Medal in the ‘60s. At this point, Knox was older, in his eighties. I didn’t realize it at the time, but he was not in good health. McGarrity said to me, if Knox doesn’t get anywhere, I think my agent would like it. When Knox dropped out, I rewrote the book, and sent it to Mark’s agent. She took it, and she’s my agent to this day. So, that advice paid off.

CG: What about your own advice to aspiring writers?

WS: There’s only two things you can tell people: read a lot and write a lot. That’s all. Nothing else you can tell them is going to help.

***