Readers unfamiliar with noir and crime fiction and other dark literature often assume the stories remain dark through the end. More often, dark stories conclude with the kinds of endings I promote in my online novel-writing class; a satisfactory ending containing both a win and a loss. Years ago, we used to teach that good endings were either “goal-achieved” or “goal-unachieved” endings. We’ve learned a lot since then about what constitutes quality writing and no longer use that kind of definition.

In my own new novel, Hard Times, after the protagonist, Amelia, endures tragedy upon tragedy, at long last she miraculously survives being killed by her villainous husband Arnold and turns the tables on him (win), and a day later she must bury one of her children (loss).

This is the kind of ending more often found. To endure page after page of never-ending pain and sorrow and to culminate in the same morass of tragedy would only be nihilism, and the best books don’t end like that.

Another example of a dark story with a hopeful ending is witnessed in Octavia Butler’s Kindred. Finding herself transported back to the days of slavery, the protagonist Dana, finds herself a slave in charge of a particularly nasty young white boy who she must keep from getting killed as he is one of her ancestors and if he dies before he fathers her ancestor, she’ll never be born. She’s transported back a total of six times—some with her white husband Kevin and some by herself. When she comes back to the present the last time, she has successfully prevented Rufus Weylin from being killed (win) so her forbear can be born, but when she reenters her contemporary life her left arm is caught in the past dimension and she loses the limb (loss). Critic Ruth Salvaggio suggests that the loss of her arm is “a kind of birthmark,” the emblem of a “disfigured heritage.”

The next example of a dark story that ends with the light of hope is James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues.” This tale is an especial favorite of mine for another reason—its opening. I often use it as an example of action beginning a story and delivering the inciting incident. It’s a great example of what the term “action” means in fiction, illustrating the difference between the lay definition of action and the literary one. In my craft book, “Hooked” I explain how this seemingly benign action fits well within the literary definition. It starts with the narrator/protagonist James Baldwin sitting on the train on his daily commute and reading the newspaper. He happens on an account of his brother being arrested for the peddling and using of heroin. Beginning writers don’t see this as “action” as they are laboring under the layperson’s definition but it is, indeed, action, even though he’s by himself and performing what appears, at first blush, a passive, not an active act But, make no mistake this is an action and serves as a beautiful example of how the terms we employ in writing carry a different and more particular meaning than in everyday language. It’s an action as evidenced by his reaction to it in the next paragraph when he realizes that from his brother’s past, this news means he is doomed to die.

In the final scene, in a jazz club, Baldwin goes to support his brother and his music, and begins in the dark place he’s been throughout, but observing the audience’s reaction to Sonny’s music leads him to the realization that brother’s music is a transforming agent of freedom and his epiphany is such that he began trapped in the darkness and has suddenly seen the light .His brother has helped him undergo a true change in that he now refuses to see the black male as a long-suffering, perpetually victimized by and longing for white society, an ending that is celebratory and triumphant and looks forward to freedom.

The next novel appears to miss the mark for books that are dark throughout and then end with hope, but it doesn’t. It just appears to at first glance. In Willy Vlautin’s Don’t Skip Out on Me, Horace Hopper is a half-Paiute, half-Irish ranch hand who wants to be somebody. He’s spent most of his life on the ranch of his kindly guardians, Mr. and Mrs. Reese, herding sheep alone in the mountains. But while the Reeses treat him like a son, Horace can’t shake the shame he feels from being abandoned by his parents. He decides to leave the only loving home he’s known to prove his worth by training to become a boxer. It’s a stark landscape he faces and bit by bit, he’s beaten down, physically and emotionally. Near death, Mr. Reese finds him, broken and suicidal, completely defeated by life, and tries to get him to come home to his ranch where he grew up. He wants nothing to do with the man or his ranch—he tells him, “Every night I’m here I hope I get run over or stabbed or thrown in prison. That’s how I feel.” He’s given up all hope. Then, Mr. Reese tells him a little white lie. He tells him he has cancer (he doesn’t), and needs him to help him with his ranch. Horace agrees to this and for the first time in a long time has hope for himself and his future. On the way back to the ranch, lying in the bed of Mr. Reese’s pickup, he dies. But, he dies with hope for himself he hadn’t had in a long time. He just ran out of time.

This next novel is especially bleak. Two things save it. I’m speaking of Helen FitzGerald’s wonderful book, The Donor. Will Marion has two perfect kidneys. His twin daughters aren’t so lucky. Question is: which one should he save? Will’s 47. His wife bailed out when the twins were in nappies and hasn’t been seen since. He coped OK by himself at first, giving Georgie and Kay all the love he could, working in a boring admin job to support them. Just after the twins turn sixteen, Georgie suffers kidney failure and is placed on dialysis. Her type is rare, and Will immediately offers to donate an organ. Without a transplant, she would probably never see adulthood. So far so good. But then Kay gets sick. She’s also sixteen. Just as precious. Her kidney type just as rare. Time is critical, and he has to make a decision. Should he buy a kidney—be an organ tourist? Should he save one child? If so, which one? Should he sacrifice himself? Or is there a fourth solution—one so terrible it has never even crossed his mind?

There is a twist I won’t reveal here for those who haven’t read it. That leads to that fourth possibility I mentioned. To save his daughters he has to commit a murder (loss). But his act does save both girls (win). The other thing that delivers the reader from the utter darkness of the book is in the character of genius private detective Preston. He is the light comic relief that this novel needed and he is my favorite character out of all of them with his many layers and odd quirks. He is the other reason that keeps this novel from being too bleak.

Joe Lansdale’s brilliant novel, Paradise Sky, is, in my opinion, the best of all his novels and that’s saying something. It fits the bill for my list here for a more traditional reason than some of the others. It’s a dark, dark novel in terms of what happens to the protagonist, Nat Love, a Black man who’s plagued like a modern-day Job with one downfall after another being sent his way by an uncaring or maybe just an indifferent God. Just about every trial he suffers being directly or indirectly at the hand of his childhood nemesis, Mr. Ruggert, who sets out to kill him after murdering Nat’s father.

After first running from Ruggert as a boy, Nat keeps growing and develops fighting skills and eventually he becomes the pursuer. Actually, each man pursues the other across the vast West, each fueled with a white-hot hatred for the other. Just before their final showdown, the father of the girl he’s fallen in love with, finally gets through to Nat, convincing him that the vengeance he’s being fueled by will be the thing that destroys him, even if he were to kill the other man. In the end, he finds his enemy and has the opportunity to kill him (win), but he passes it up and takes him back to town to face the hangman and justice (loss). It’s dark until the very end and no reader would have blamed him for killing the evil Ruggert, but hope for him as a man illuminates his final choice when he chooses justice over revenge.

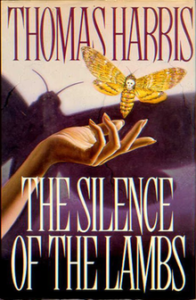

There is one other category of story that is dark throughout but has a hopeful ending and those are stories that have thoroughly venal characters who remain dark until the very end. One of my advisors during my MFA in Creative Writing at Vermont College, Sharon Sheehe Stark (A Wrestling Season), introduced me to this rare sort of character with her theory that the very best evil characters are those that are true to their nature throughout. To create this kind of character, Stark advises the writer to not employ that copout tactic of “having the bad guy like kittens.” She opined that instead, to have your character “hate kittens.” To have him remain dark throughout, as “the light will shine through the cracks.” A brilliant method, but one that results in the very best of all stories. Think of characters like Hannibal Lector in Thomas Harris’s The Silence of the Lambs, for instance. He’s not 95 percent evil, or even 99 percent. No, he’s 100 percent a depraved individual. And yet, one of the most interesting characters in literature. And one of the most liked and most admired, even though he seemingly has no redeeming features whatsoever.

But he does have one redeeming feature—his choice of victims. Most are considered pariahs in civilized society. Additionally, his interactions with FBI trainee Clarice Starling, while cruel, lead her to capture another serial killer who preys on the innocent. And these two choices by the author provide the “light” that shines through the cracks that keep the story from remaining dark throughout—and make it completely compelling as well.

***