As it’s been said lately, Netflix is all either murder or cakes. Our appetite for crime in shows, movies, or books is—and probably has always been—seemingly insatiable. Growing up, my sister was a true-crime buff, and the original Law and Order was a staple in our rotation when we got older, which I realize now is dating me a bit. Crime is everywhere and in seemingly every form: fictional, true, procedural, cerebral, violent, forensic, legal, white-collar, solved, and unsolved. But from what I’ve read and watched, one aspect is largely underrepresented: the victim’s perspective.

Though many perpetrators of financial or other white-collar crimes convince themselves that the wrong they’ve committed is victimless, wrongdoing leaves behind it a wake of people who bear the brunt of the consequences. In most cases, though, when a crime is served up for our consumption (either as entertainment or morbid education), the victim appears only just enough to profile the unidentified subject and narrow the search. Let’s face it: in these depictions, murder is almost always the crime, so the victim is dead. They are merely the initial mystery that has to be solved first to unlock the larger one of their violent death. We are presented with weeping relatives or bewildered neighbors or numb roommates who paint the barest snippets of the victims’ lives, but that is a dramatic oversimplification of how people are affected by crimes—just as murder is a narrow lens through which to examine crime in general. In the real world, murder accounts for a small percentage of all felonies, even a small portion of all violent crimes.

My novel, Upended, opens with an assault, but the focus of the story is not the crime itself but its wide-ranging effects not only on the primary victim but of everyone who is close to her—effects that are (spoiler alert) vast. Though murder now comes packaged in neat one-hour episodes, eight-installment “limited series,” or 300-page books, the aftermath of these deeds resonates widely and has a half-life of years, which doesn’t fit easily within these bounds. This is what makes fiction such a compelling tool when focusing on the victim’s perspective. Unlike reportage, it allows great flexibility around point of view, timeline, and interconnections, all of which can be critical aspects in the quest of trying to get readers to truly understand and empathize with the aftermath of tragedy. Fiction can address multi-generational trauma and the fuzzy edges of violence’s reach in a way that would be impossible in non-fiction due to both time and cost.

Fiction can also more deftly address the hidden price paid by victims of violent crime. What does it feel like to be afraid in your own home or to want to move on but be incapable of it? How can you accept the senseless and inexplicable? What can you do when someone you love is changed by what has happened to them? What happens when roles are reversed and a historically strong and capable person emerges wrecked and scattered? How do you handle (or not) the unending stream of internal questions of “what ifs” and “if onlys” and “why”? Can someone ever truly be the same after something horrific has happened to them or someone they love? Should they be?

In my book, my main character, who had an “unhealthy” relationship with the truth before the attack, says this: “Lying, she was reminded, was not just the lie itself but all the living with it you had to do afterward.” The same is true of victimhood (or survivorship) in general, and the following works of both fiction and non-fiction are great examples that explore this topic in depth and that I read in part to help me craft my own work.

Kathleen Kent’s The Burn

This follow-up to Kent’s 2017 book The Dime follows Detective Betty Rhyzyk after the wringer Kent put her through in the first novel in this series, and there’s nothing not to like about this book. Kent pairs Rhyzyk’s physical and emotional recovery from the events of the first book with a new (or is it an ongoing?) investigation, and the weaving together of Betty’s role as an investigator and her reality as a survivor deepens both sides of the equation. Told through Betty’s point of view, we get a first-hand account of the scars of what she experienced in the first book, the difficult path to recovery, and the strain it places on the relationships with the people closest to her.

Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life

Love it or hate it (and I did both at the same time), this tome sinks into the psychic scars and lasting effects of the repeated and horrifying trauma its main protagonist, Jude, experienced. Like The Burn, Jude’s struggles are both physical and emotional, and they resonate through every aspect of the story. Unlike The Burn, we see how difficult these scars are to escape over the course of a lifetime and how they affect everyone who is invested in the wellbeing of a crime’s victim. Yanagihara chose to tell this story with multiple points of view, each deeply embedded within the individual character’s psyche, as well as an expansive timeline. These two approaches, both of which are powerful tools in fiction, heighten the connection readers have to the long and tangled aftermath of trauma.

Laurie Halse Anderson’s SPEAK

Some people call this the seminal young adult book about sexual assault, and for good reason. In SPEAK, the protagonist not only has to reckon with being sexually assaulted at a party but also the ramifications from her peers after speaking out about that assault. This book illustrates the far-ranging effects of assaults and the difficulty in navigating other people’s reactions to being a survivor of such a crime.

Maggie Nelson’s The Red Parts

Though the author is one generation removed from the victim of the central crime in this “autobiography” of a trial, she examines how her aunt’s murder, a cold case that is reopened on DNA evidence and that goes to trial, reverberated through her family. As with much of Nelson’s work, she leverages non-fiction in personal ways and avoids a cold, reportage-style distance. It is an elegy on trauma and its multi-generational consequences and reminds us that every crime causes a ripple effect of devastation.

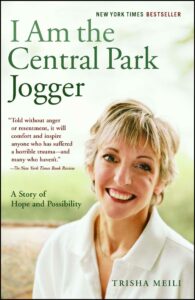

Trisha Meili’s I Am the Central Park Jogger

The title says it all. For years, the Central Park Jogger’s identity was a closely held secret, but this book shines a bright light into her experience of mental and physical recovery after being brutally raped and beaten. Most of this book focuses on the incredible struggle to overcome her traumatic brain injury, which is often an underreported cost of violent crime.

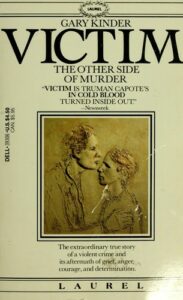

Gary Kinder’s Victim

This detailed look at a horrific robbery-homicide in Ogden, Utah, in 1974 is striking for its almost singular focus on how one family was affected by the crime. Courtney Nesbitt and his mother Carol were two of five people held hostage during a robbery. They were eventually forced to drink Drano and were shot in the head by one of the perpetrators. Against all odds, Courtney survived, and the book follows his father and siblings through a year of his recovery, delving deeply into how they were affected by Carol’s death and Courtney’s physical struggles and ongoing disabilities.

***