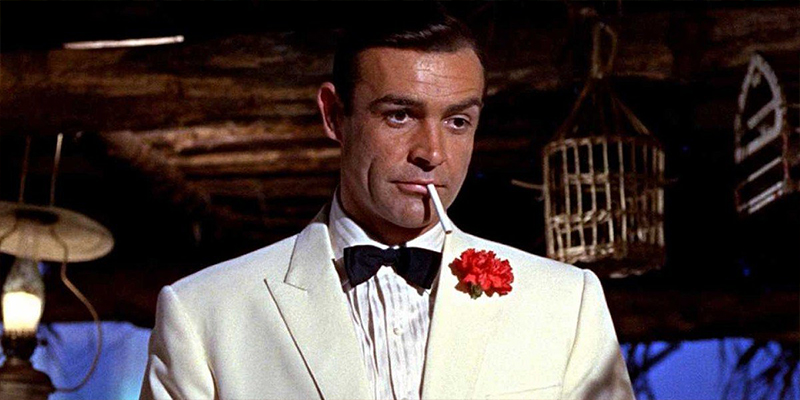

Who doesn’t love Ian Fleming’s James Bond? Most professional intelligent officers, as it turns out. Oh, we don’t hate him, but I’d say that, at best, we have a love-hate relationship with him. It tickles us that the public thinks we could be that suave and charming, that physically competent (running for miles without vomiting! Swinging from construction girders like a chimpanzee!) and mentally focused. We know that the truth is nothing like what you see on the big screen.

My view is doubly tainted because in addition to working my entire adult life for the likes of CIA and NSA, I also write spy stories. I’ll admit that after I wrote my first spy novel in 2021, Red Widow, it was hard not to be resentful or jealous of the James Bond character’s great popularity.

Which is why I wrote The Spy Who Vanished. Yuri Kozlov is Russia’s top spy, their James Bond. So, when he decides to defect to the CIA after Putin invades Ukraine, it’s too good for the Agency to pass up, even though the offer has “danger” written all over it. As it turns out, they were right to worry because—spoiler alert—Kozlov is a double agent, a ploy dreamed up by Putin after being embarrassed by the numbers of Russian agents turning to the West. But even as Kozlov is executing his mission at a CIA safehouse in the Virginia countryside, he has doubts. He doesn’t trust that Russia really has his back—if it ever did.

Writing The Spy Who Vanished allowed me to work out my confliction from inside the mind of a Bond doppelganger, and it was an enlightening experience. I was able to explore what makes Bond iconic. What was it like to be him, especially in the twilight of his career. What would be more important to him, his regrets or his triumphs? Ultimately, the story examines the profession of espionage as a whole. What is it that makes it different from all other professions? What sacrifices does it demand of its practitioners? How does it change you as a person? What does it do to your soul after so many years and so many kills?

How does James Bond rate as a spy? Well, in my opinion, what you see on the screen is often the antithesis of good intelligence work. The main job for real life operations officers is persuading foreigners with access to the secrets you need to part with those secrets, usually for money or because of ideology. The average case officer is not an assassin or saboteur, sent out into the world with a license to kill. An assassination, however, is easy for film audiences to grasp and retain amid the whirlwind of travel, romancing, and chase scenes on the screen.

The real job is a team sport, though you wouldn’t know it from Bond movies. While there is often a leggy female sidekick and Q providing a few gadgets, Bond operates more or less on his own. This is not the case in real life, where the work increasingly relies on a mix of skills, particularly technical specialties. It is less and less about the lone wolf.

To be brutally honest, it’s hard not to see James Bond as fantasy fulfillment. A life with no messy connections or commitments, where you’re simply given a pile of cash, a gun, and a plane ticket. A life where there are few if any consequences (the Daniel Craig Bond movies aside). Fantasy is fine, but it has its place. You can’t claim to be an advocate for, or interested in, the intelligence business if you ignore its reality.

I’m not alone in my reservations: even MI6 acknowledged the double-edged nature of England’s most famous spy in a 2021 Twitter campaign #ForgetJamesBond. While former chiefs of MI6 have acknowledged that Bond is “a great recruiting tool” and a “powerful brand”, it’s also been a diversity-killer, particularly when it comes to convincing women to join the service. A one-time head of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service cited Bond’s ego and narcissism that would make him difficult to work with.

One of the greater dangers, however, is that the public will mistake what is seen on the screen for what intelligence agencies can do in real life, and yet this happens. In Amy Zegart’s excellent book, “Spies, Lies, and Algorithms”, the Stanford professor cites examples of congressional aides and military commanders admitting that they looked to “spytainment” like the show 24 to design operational missions. As a matter of fact, she got the idea for her book when she saw how little her own students knew about real intelligence work. Zegart’s shock is something intelligence professionals deal with every day, whether from neighbors reacting to newspaper headlines or people gushing over the latest streaming spy show. That’s not how it works, we mutter to ourselves through gritted teeth.

Let’s hear it for real-life intelligence professionals. We may not look as good in a tuxedo or swimsuit but, on the whole, we’re more thoughtful, law-abiding, and professional than James Bond any day.

***

Alma Katsu’s latest espionage story, The Spy Who Vanished, is an Amazon Original Story available on Kindle and Audible.

Note on terminology: While the term “spy” is commonly used to mean someone working in this field, technically it refers to the person, usually a foreigner, who has been recruited by an intelligence service, also known as an asset. Intelligence professionals—those employed by a national intelligence service—are typically referred to as “officers”.