If YOU ASKED PEOPLE WHAT body part you would associate with Anne Boleyn, most would probably say her head. Logical, of course. It was the part famously detached from the rest of her body on May 19, 1536, at the orders of her husband, English king Henry VIII. Henry had broken with the Roman Catholic Church to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, to marry Anne. But when she failed to give him the male heir he so desired, he decided to move on to another wife (Jane Seymour, wife #3 of his eventual six wives), accused Anne of treason and adultery (even with her brother), and ordered her execution.

But let’s put Anne’s head aside. It is her heart that concerns us here, a heart that, according to stories, was also separated from her body. Some say that Henry, still in love with her, requested that her heart be removed so he could keep it even while the rest of her body was buried without Christian rites in an unhallowed grave in the Tower of London. Others say that Anne made a final request that her heart be taken to the church in Erwarton, Suffolk, where she had been the happiest. No one is sure which story is true, or even whether her heart was taken out of her body at all, since it had been the rage in the past but wasn’t very common by the time of Anne Boleyn’s death.

Let’s step back a bit to medieval times, when taking the heart from a body and burying it separately (or otherwise keeping it, in a decorative box or a bag) was de rigueur, particularly among the upper classes. It was just one aspect of what’s called “dispersed burial.” Since something that is dispersed is something spread over a wide area, you can rightly conclude that the only way to make a burial dispersed is to make the body dispersible—disassembled, if you will—i.e., cut into different parts so as to be able to inhabit a fair amount of real estate.

Disembowelment and embalming had been practiced since the 7th century in European countries, particularly north of the Alps, but the whole idea of burying a less-than-whole body really caught on in a big way during the Crusades, the wars fought between Christians and Muslims between 1096 and 1291. Because those who were killed on the battlefield were so far from home and usually in a hot climate, it was difficult if not impossible to transport the corpses home intact for burial in consecrated ground. The way around this? Take part of them home: bones, entrails, or, most popularly, hearts. Thus were Crusaders neatly and compactly returned to their native lands for burial.

Because most of the Crusaders tended to be aristocrats, dispersed burial became associated with the upper classes and it became desirable primarily due to snob appeal. People wanted to follow in the footsteps of the likes of Richard the Lionheart who requested a tripartite burial, with his heart buried in the cathedral of Rouen; his brain, blood, and entrails in Charroux; and whatever was left over buried by his family in Fontevrault. While most people weren’t quite so dispersed, they liked the concept. It was a sign of status to have your heart buried in the family shrine while your body reposed in the local church. Speaking of local churches, they welcomed the practice wholeheartedly. It was a way of spreading the wealth, literally: When more than one religious establishment housed parts of a dead emperor, king, or lord, each got funding.

But the Church with a capital C in the person of Catholic pope Boniface VIII did not approve. Boniface thought it an abomination and wrote a bull, an official formal decree, banning it in September 1299. Perversely, the ban made dispersed burial even more desirable. Because a person needed dispensation from the pope, arranging one became the ultimate 14th-century status symbol. Some took the concept of dispersal to the nth degree, like Cardinal Béranger Frédol, who, in 1308, got papal dispensation to have his body buried in as many different places as he wished. (Sadly for him, it appears that in spite of his grandiose and widespread plans, he was buried in only one piece and so in only one place. This is one of the drawbacks of after-death plans: You are not around to ensure that your arrangements are followed.)

So even though the church weighed in against it, the custom persisted, particularly among the bold-faced names of the Middle Ages. By the mid-14th century, Pope Clement VI pretty much bucked his predecessor Boniface’s intention, and gave a sweeping dispensation allowing all the French royals to split up their bodies however they saw fit. It then became quite common to have a body interred in church for public veneration and a heart given to the deceased’s family for a more intimate burial. The fad began fading out a bit in England after the 1400s, but dispersed burial, particularly heart burial, continued strong in France and Germany through the 1800s.

Which leads us back to Anne Boleyn and her heart. Since heart burial wasn’t a terribly common thing anymore in England in the 1500s, there’s a lot of debate about that particular organ. Was it removed from her body by her ex-husband as a sentimental keepsake? Was it removed and taken to Sussex in line with her last wishes? Or was it just left in her chest? No one is sure.

What we do know is that a small inscriptionless heart-shaped tin casket was found in the chancel wall when St. Mary’s Church in Erwarton was undergoing renovations in the mid-1800s. The clerk of the church said that a story handed down through the generations held that Queen Anne’s heart had been buried there according to her last wishes, and this must be it. The casket contained only dust (which could once have been her heart). That was good enough for the church. They reburied it under the organ and put up a small plaque marking it as the probable burial place of Anne Boleyn’s heart. It has become popular with tourists, who, after seeing it, can go wet their whistle in town at the local pub, the Queen’s Head.

_________________________________

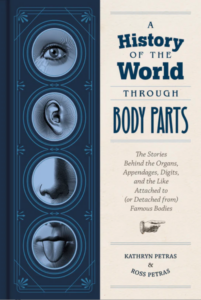

Excerpt from A History of the World Through Body Parts: The Stories Behind the Organs, Appendages, Digits, and the Like Attached to (or Detached from) Famous Bodies by Kathy and Ross Petras. On Sale 8/30, ISBN 9781797202846. Published by Chronicle Books.