Unlike me, not every reader has been a die-hard fan of mystery fiction for decades. More likely, you are a fan (else why would you be on a site titled CrimeReads?) but not totally devoted to the genre and basically just looking for some recommendations of what to read but unsure about the various categories by which books may be defined. As a geek who has been professionally involved with crime fiction for nearly a half-century, maybe I can help.

I tend to embrace a wide range of fiction into the mystery genre, defining it as any work of fiction in which a crime or the threat of a crime is central to the theme or plot. This includes the form that most readers regard as a mystery, which is the traditional detective story but a category of literature that also includes the police procedural, the hard-boiled novel, the tale of psychological suspense, the crime novel, and the thriller. There is enormous overlapping of these sub-genres and it is often difficult to categorize some books.

It is my plan—indeed, my mission—to define these categories, describe their strengths and weaknesses, and provide numerous examples from both the past and the present to help guide readers to the type of book they are most likely to enjoy.

This is the fourth of several columns in which I try to define the major sub-genres. Number one was about the Traditional Detective Novel, and number two focused on Hard-Boiled Fiction and the third focused on the Thriller. Today, the police procedural.

THE POLICE PROCEDURAL

In terms of solving a crime, the most realistic approach is offered in stories in which the police are the dominant figures. Let’s face it: When a murder occurs in real life, you’d probably prefer the police to come on the scene than the local vicar, a personal trainer, or a bookseller.

There are really three types of cop novels and it’s difficult to separate them because they all have elements of the other examples. In the first, a policeman is called in to solve a crime and sets about doing it. He acts alone and, apart from his training and official position, functions pretty much the way an amateur sleuth or a private investigator would.

Much later in the development of the cop novel is the creation of the police procedural, in which an entire squad cooperates to find the killer. There are uniformed cops, followed by detectives, medical examiners, forensic experts, psychologists, sketch artists, etc. Of all crime fiction, these are the closest to the real deal.

In the most literary of the police sub-genres is the novel that looks at the lives of the cops involved in investigations. The cops do not follow procedure and the books often seem less concerned with solving a mystery than examining the complex lives, motives, strengths, and weaknesses of members of a police force.

STRUCTURE: In most all cop novels, a crime (usually murder) is committed and the police are called. In one kind, the killer is hunted by a lone cop (or, frequently in modern stories, with a partner). The investigation is seen through his eyes and, while he relies on other people in the station house or precinct for help, it is generally his insights and doggedness that unravel the mystery. Loners abound, and so do rogue cops who have little difficulty breaking the law to nail the perp. They are frequently in trouble with their superiors and often the target of a psychopath who thinks himself a criminal mastermind. They also have difficulty with the FBI, the D.A., journalists, and their wives.

The police procedural is more of an ensemble piece. Although inevitably certain characters are more interesting or intelligent than others and get more space, putting the bad guys away is a team effort. The methodology of detection is based on real-life police work, the crimes are thrust upon them rather than selected by free choice, and they frequently become involved with several cases at the same time.

In the final sub-sub-genre, the investigation often continues off the page while members of the force are out drinking together and telling stories, or they’re involved with women to whom they’re not married, they’re dealing WITH money problems, helping their kids, getting divorced, engaged in a nefarious scheme—all the things that make them recognizably human, neither evil nor angelic.

HOW TO TELL: If you are looking at a book with a badge on the cover, you can rest assured it’s a police novel. While this is the most common of all clichés, others include a police car, especially if its flashing red lights are in evidence. Titles may include a specific precinct or a bit of police terminology, such as “Code 6.”

THE BEGINNING: The first novels using policemen in very prominent roles happened to be by two of the greatest writers of the 19th century, Charles Dickens (with Inspector Bucket in Bleak House) and Wilkie Collins (with Sergeant Cuff in The Moonstone, which T.S. Eliot, a devoted aficionado of mystery fiction, described as the first, the longest, and the best mystery ever written; he was wrong on all three counts, but never mind). In France, Emile Gaboriau’s M. Lecoq was immensely popular, but it was Francois Vidocq, a former criminal who created the first organized police force, the Sûreté, whose memoirs first described investigative techniques in 1828.

As time passed, the police were frequently offered up as incompetent nincompoops while amateur detectives and private eyes took center stage.

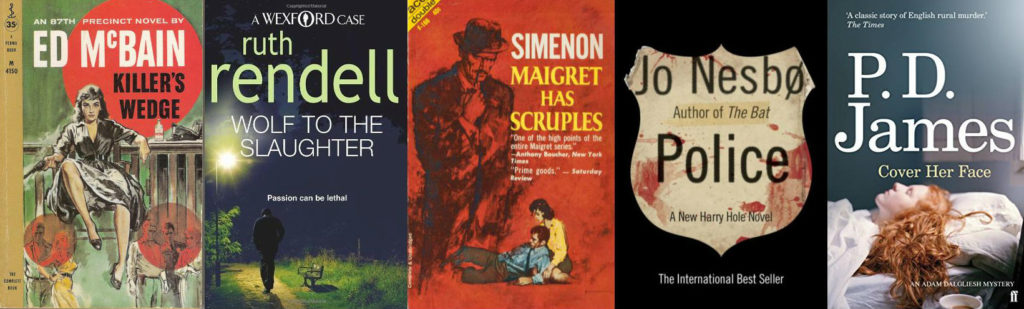

The police procedural is generally regarded as having been created by Lawrence Treat in 1946 with V as in Victim. The author wrote eight more procedurals, but they never achieved major success. Hillary Waugh did, with his 1952 novel, Last Seen Wearing, but it was Evan Hunter, writing as Ed McBain, who really put the procedural on the map. The first novel in the 87th Precinct series, Cop Hater, was published in 1956, and he was still writing with the same vigor and creativity a half-century later when his last novel, Fiddlers, was published before his death in 2005.

THE GREATS: Dickens, Collins, Ngaio Marsh (with Roderick Alleyn), Colin Dexter (and his beloved Inspector Morse), Reginald Hill (Dalziel and Pascoe), P.D. James (Adam Dalgleish and Cordelia Gray), and Ruth Rendell (Inspector Wexford) lead the parade of British police writers. The best of the British procedural writers may well have been the little-known J.J. Marric, whose Insp. Gideon adventures quickly became classics. Others include Bill Knox, Maurice Proctor, and James McClure, whose South African duo of Tromp Kramer, a white man, and Mickey Zondi, a black man, had a lamentably short career.

In Europe, after Gaboriau there was the Belgian Georges Simenon (creator of the wonderful Parisian detective, Maigret), who wrote prolifically from 1931 to 1977. Today, the best-selling writer (and deservedly so) in the police genre is Jo Nesbo, whose Harry Hole is a member of the Oslo police department.

Of Americans, the most distinguished cop writers after the iconic McBain include Treat, Waugh, Dorothy Uhnak, Lillian O’Donnell, Dell Shannon, K.C. Constantine, William J. Caunitz, ex-Deputy Police Commissioner in New York, Robert Daley, and, in a different milieu, Tony Hillerman and his Navajo cops.

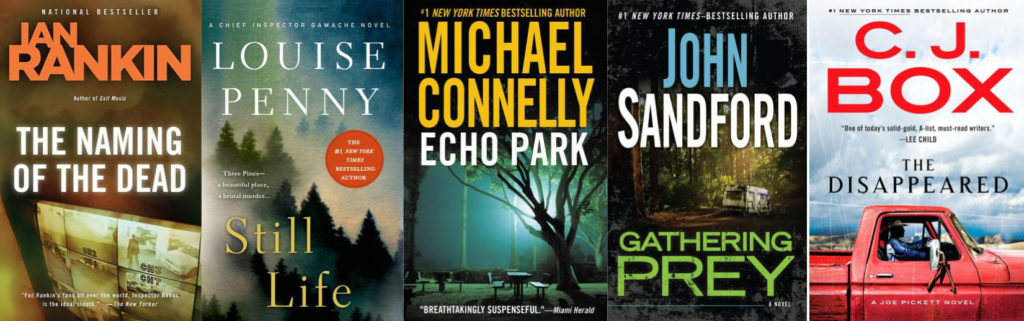

BEST OF THE MODERNS: In England, Ian Rankin (John Rebus), Bill James (Colin Harpur), and John Harvey (Charlie Resnick), all of whom have written some of the most distinguished fiction being written in any genre, lead the way, though none is a purely procedural writer. The closest is Peter Robinson, now living in Canada, whose Alan Banks series is outstanding. Canada is also the home of Louise Penny and her distinguished series featuring Chief Inspector Armand Gamache of the Sûreté du Québec.

American police writers must pay obeisance to Joseph Wambaugh, who showed what it was really like to spend your life in a uniform. James Ellroy credits the former cop with giving him direction, and there can be little doubt that such super-stars as Michael Connelly (whose Harry Bosch is in the pantheon of all-time great detectives), John Sanford (whose Lucas Davenport regularly and deservedly make the best-seller list), Jeffrey Deaver (whose Lincoln Rhyme series features a former NYPD detective, now working as a consultant since he became a paraplegic) and James Patterson (whose Alex Cross novels are among the biggest selling books of all time) were influenced by Wambaugh as well.

Other important members of law enforcement include Nelson DeMille’s John Corey, an NYPD homicide detective who retired from wounds received on the job and then was hired as a contract agent with the Federal Anti-Terrorist Task Force; C.J. Box’s Joe Pickett, a Wyoming game warden, and the excellent series about FBI Special Agent A.X.L. Pendergast by Doug Preston and Lincoln Child.

As an aside, attempting to put any procedural writer in the same league as McBain is akin to finding a playwright who should be mentioned in the same breath as Shakespeare.