Unlike me, not every reader has been a die-hard fan of mystery fiction for decades. More likely, you are a fan (else why would you be on a site titled CrimeReads?) but not totally devoted to the genre and basically just looking for some recommendations of what to read but unsure about the various categories by which books may be defined. As a geek who has been professionally involved with crime fiction for nearly a half-century, maybe I can help.

I tend to embrace a wide range of fiction into the mystery genre, defining it as any work of fiction in which a crime or the threat of a crime is central to the theme or plot. This includes the form that most readers regard as a mystery, which is the traditional detective story but a category of literature that also includes the police procedural, the hard-boiled novel, the tale of psychological suspense, the crime novel, and the thriller. There is enormous overlapping of these sub-genres and it is often difficult to categorize some books.

It is my plan—indeed, my mission—to define these categories, describe their strengths and weaknesses, and provide numerous examples from both the past and the present to help guide readers to the type of book they are most likely to enjoy.

This will be the third of several columns in which I try to define the major sub-genres. Number one was about the Traditional Detective Novel, and number two focused on Hard-Boiled Fiction. Today, the thriller.

THE THRILLER

The decline of the pure detective story in recent years was probably inevitable. After all, there are only so many motives for killing someone, and contemporary society largely removed one of the most popular (killing a spouse because of another love interest seems utterly Victorian nowadays, with divorce so easy to obtain), and even school children know that the police should “follow the money” for the other most common motive.

Few authors have the ability to contrive complex mysteries, with apparently air-tight alibis being broken down, clues placed so cleverly before the reader’s eyes that they fail to see them or understand their significance, and motives so powerful yet believable that the killers are not merely a necessary piece of the puzzle but part of a cohesive and satisfying story. Besides. Agatha Christie used up most of the good plots in her prolific career.

As heroes and heroines of today’s traditional mysteries have come to rely more and more on coincidence, luck, a hunch, or a genius house pet to solve crimes, readers have also become less demanding of contemporary writers, being willing to settle for a less-than-perfect plot just so long as they like the lead character.

Too, many readers have become impatient. Bombarded daily with a few lines of social media, quick cuts of movies, television programs and commercials, they are unwilling to work through discussions of railroad timetables, tides, or how long it takes for a sprig of parsley to sink into a bar of butter on a summer day. They seek movement and action—hence the increased popularity of the thriller.

The thriller genre, like all the categories of mystery fiction I have been attempting to describe and illustrate during the past few columns, is as difficult to define as art or pornography, and its borders are as fuzzy as my memory after a second bottle of wine. Among its components are tales of espionage, political nastiness, financial schemes, adventure, some military fiction, high-tech shenanigans and even weird religious plots.

STRUCTURE: A single hero (or, in very recent years, with increasing frequency, heroine), a partnership or a small group of experts battle a foreign power, a criminal organization or a ruthless super-genius intent on ruling (a) America, (b) the world, or (c) a phenomenal amount of money. There is a great deal of action (with the notion of “possible” replacing that of “probable”) involving very fast vehicles, serious weaponry, lots of explosions, a huge body count, a fearless, incorruptible decathlete and the most beautiful 30-year-old woman in the world who is also the world’s leading expert on something or other; she is always single.

HOW TO TELL: The book is frequently thick, and its dust jacket (or cover, as many thrillers are paperback originals) will certainly feature an American flag, a swastika, a hammer and sickle, or Arabic lettering and someone wearing a burnoose. An illustration of an explosion and a weapon, as well as a photograph or an artist’s rendering of the aforementioned woman in very tight garments running toward or away from someone or something, frequently while holding the hand of that very handsome and muscular guy. Large pieces of modern machinery are often in evidence, as is the figure of a monomaniacal fiend of some stripe. Such lines as “the fate of the world” and “only x can prevent” have a good chance of appearing, as do “heart-pounding,” “fast-paced” and “explosive action.”

BEGINNING: Although spies have always been with us (note Judas Iscariot) and so have figures intent on world domination (Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan), the literary thriller did not begin until 1821, when James Fenimore Cooper wrote The Spy, the story of a heroic American agent during the Revolutionary War. Distinguished authors as well as hacks, almost always British, went on to write spy thrillers, notably Erskine Childers with The Riddle of the Sands, Joseph Conrad with The Secret Agent, E. Phillips Oppenheim, the author of more than a hundred books, most of which are thrillers, and W. Somerset Maugham, whose Ashenden is frequently cited as the origin of the modern espionage novel.

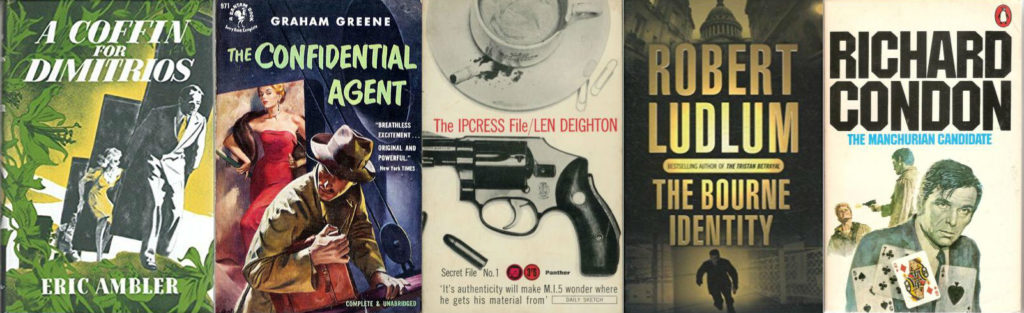

THE GREATS: John Buchan (his Richard Hannay novels, especially The 39 Steps), Eric Ambler (A Coffin for Dimitrios and Epitaph for a Spy), Graham Greene (The Third Man, This Gun for Hire, Orient Express and Confidential Agent), Ian Fleming (and his utterly unrealistic but nonetheless captivating hero, James Bond), John Gardner (who wrote more Bond novels than Fleming but whose best work is about Big Herbie Kruger, including one of the half-dozen greatest spy novels ever written, The Garden of Weapons), Len Deighton, Alastair MacLean, and Adam Hall, creator of Quiller, all of whom are British.

Among Americans, don’t miss Ross Thomas (who wrote every type of thriller imaginable, no two alike), Robert Ludlum, Francis Van Wyck Mason and his Col. North series, Richard Condon (The Manchurian Candidate), Thomas Gifford (The Wind-Chill Factor), and Brian Garfield (Hopscotch).

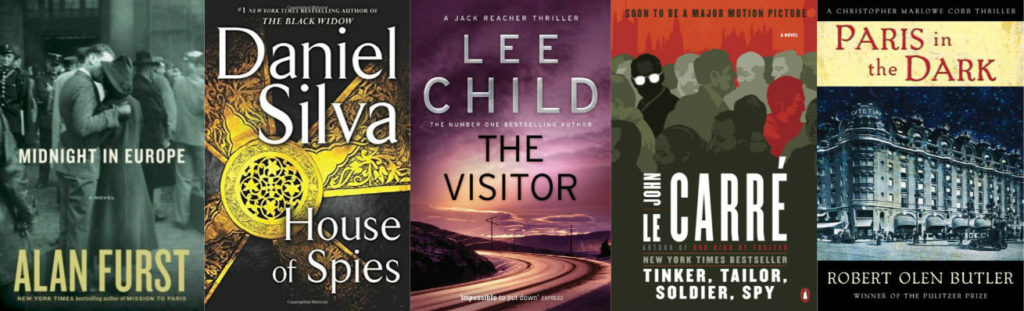

TODAY’S BEST: The great Charles McCarry (the most poetic of all American spy writers, especially The Tears of Autumn, The Secret Lovers, and The Last Supper); Alan Furst (who has taken the mantle of Ambler and wrapped himself in it with his World War II thrillers); Lee Child and his iconic hero Jack Reacher; Daniel Silva’s outstanding series about Gabriel Allon, an Israeli art restorer, spy and assassin; Robert Olen Butler, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of the World War I thrillers featuring Christopher Marlowe Cobb; Jason Matthews, whose Red Sparrow might be the best thriller of the past decade; and Nelson DeMille, who manages the rare feat of writing beautifully and being a bestseller, lead the Americans.

Among the best of the British writers working today are John le Carré, who has no peer as a prose stylist (famously in the Karla novels, Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, The Honorable Schoolboy and Smiley’s People, as well as the iconic The Spy Who Came In from the Cold), Charles Cummins (I can’t pick one title because they’re all so good), Frederic Forsyth (whose The Day of the Jackal is white knuckle suspense), bestselling Ken Follett (whose Eye of the Needle began a monstrously successful career), and Brian Freemantle (whose Charlie Muffin series brings the rare element of humor into the thriller).