So who would be nuts enough to write a novel with six viewpoint characters who have nothing in common except for their connection to an old self-storage facility? Apparently, me.

My previous three novels, The Art Forger, The Muralist and The Collector’s Apprentice, were all historical art-themed stories told in multiple voices across multiple times in multiple locations with multiple plotlines. When I sat down to write my next novel, I decided to do something different. And easier. My plan was to create a present-day story that takes place in Boston—where I live—rather than Paris or Philadelphia or NYC, where I don’t. It wouldn’t have anything to do with art, and it would have a single storyline, a single protagonist and be told in a single voice. Things didn’t exactly work out that way.

I blame this on an article I read in the Boston Globe about a self-storage facility built over 120 years ago in Cambridge, Massachusetts, including photos of the five-story brick monstrosity resembling a medieval castle—including turrets—sitting across the street from MIT. And inside, open doors revealing a motley crew of people and the even more motley possessions they couldn’t part with. Who could resist such a setting?

I also blame the documentary “Finding Vivian Maier,” for turning me onto street photography; the novel Let the Great World Spin, for the idea of an ensemble cast previously unknown to each other; and the video “The Race of Life,” which got me thinking about the relationship between where we start out in life and where we end up.

Exit the no art/single story line/single narrator plan. Enter Metropolis. Although the novel is set in present-day Boston, it’s a compilation of seven or ten or twelve different plots—depending on how you count them—with six major viewpoint characters, and street photography is an important element.

These characters couldn’t be more different from one another, on completely different paths in life, each with their own separate struggles and secrets. Black, brown and white. Christian, Jew and atheist. Gay and straight. Rich, poor and in the middle. And yet here they are, their stories intermingling in unexpected ways, creating a suspenseful tale that’s wrapped around a mysterious accident—if it was indeed an accident—that pulls them together and tears them apart.

So how the hell does one go about writing a novel with such a large unconnected cast and so many intertwining plots? Well, how about Excel spreadsheets, bar graphs, bubble maps, pie charts and scattergrams? Not to mention intersecting and overlapping normal curves. Not the usual items in a novelist’s toolkit. But my tools, nonetheless. Granted, I have a math background—one of my areas of specialization in graduate school was statistics—and everyone knows that being able to invert a matrix is a prerequisite for a successful literary career. Or not.

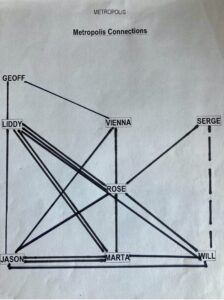

The bubble maps came first. Which of the characters know each other? Which don’t? And how does this change over the course of the book? Many bubble maps. Rose, the manager of Metropolis, is at the center, as she has met all the other players when the story begins, but no one else has interacted. By the final bubble map, almost everyone knows each other—although some characters have dropped out of the story, others names have been changed, and then there are those who switched plot lines. In the end, some have crushes, some are in love, some are helpers and some are friends. And there are those who knowingly cause the downfall of others.

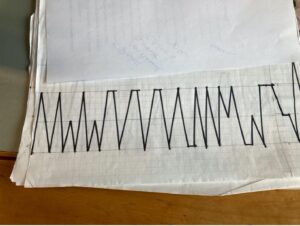

Obviously, each person is the hero of their own story, but who are they? What are their dreams, hopes, problems? You may not be aware of this—because I made it up—but every plot can be mapped on a normal curve. This is true of all character arcs and subplots, and is exactly what I needed to get Metropolis to work.

I started with Rose, graphed out her normal curve, her story, with all its obstacles and conflicts and major plot points. Then I did the same for the other five, as well as the subplots, along with the overarching plot that ties them all together. When each of these was complete, I combined them into a single graph, with time running across the X axis, the one on the bottom, and the progression of events on the Y axis, along the left.

But how to organize this into a cohesive novel? For this I used a very sophisticated statistical method: multi-colored file cards. Each character, sub-plot and plot gets a color, and each card represents an individual’s plot point. For example, Rose had about twenty plot points, and I put each one on a single red file card. Of course, red. Marta had about fifteen plot points, and because she’s hiding from ICE, I pulled out fifteen green cards for her. And on and on with each plot and each character.

Then I took all the cards and laid them out on my dining room table and moved them around until I created a structure that had a beginning a middle and an end. When that was complete, I formed the cards into sequential scenes based on a four act structure—I especially like it many different colored cards end up in a single scene, as this is sure to make it a tense one. Then I began to write.

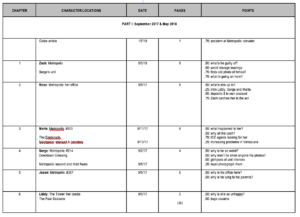

But writing wasn’t the end of statistics and charts. Far from it. Throughout the process, I kept a tension chart for every chapter. The chart includes when, where and who is narrating each scene, but most important is the “tension coefficient” I assigned to each scene—as well as a short description of what happens. My coefficients ran from 0.25 through 1.0, reflecting the amount of emotion I believed the events created.

Obviously, you can’t have a scene with no tension because that would be totally boring, but sometimes you have to do a bit of backstory or buildup or just need to give the reader a break after a high-tension chapter. This type of scene got a tension coefficient of 0.25. It was 0.50 for those with a cliff hanger, 0.75 for those where three or four different colored file cards intersect, and the big 1.0 for the really, really big ones.

When I finished the first draft, I plotted the coefficients on graph paper. If there were too many low numbers in a row, I knew I needed to add something to keep the reader reading. And if there were too many high numbers clustered together, then it was clear the reader needed some breathing room.

But this was just the skeleton. For me, the magic is in the revisions. Where my imagination adds the muscles and skin and faces to the characters, where the themes and plots are deepened, where true connections emerge. This is when my story becomes different from every other story. The right brain and the left brain working together. In the case of Metropolis, through nine drafts, almost four years, and many iterations of normal curves, bubble maps and scattergrams. Not to mention those many, many boxes of multi-colored file cards.

***