My favorite thrillers are character studies with a crime hook. They’re books about people’s actions, reactions, behaviors, and emotions set to the backdrop of a suspenseful mystery. They are first about characters and second about crime. Books like Luckiest Girl Alive by Jessica Knoll (featuring a Columbine-like shooting), Whisper Network by Chandler Baker (featuring #MeToo-like storyline), and The Girls by Emma Cline (featuring a Manson-like cult) are great examples. We fall under the main character or characters’ spell because their voice jumps off the page. We root for them, we hate them, we love them, we want to see them thrive, or want to see them suffer. Either way, we become deeply invested.

There is a thin, blurred line separating a compelling story from gossipy exploitation with regards to writing fiction based on true events. The best way I’ve found to combat that is to create the most irresistible, captivating characters; characters that make the story about them and their experience, rather than the true events that the book is based on or inspired by.

While plotting Luckiest Girl Alive, Knoll spoke about the research that went into writing a high school shooting. “Columbine is a story that has always fascinated me,” Knoll told an Austin newspaper. “I had read with Columbine that they always thought there were other people involved, but couldn’t prove it, and I thought about what it would be like to have that shadow following you around your whole life. Something that made you desperate to prove yourself.” That’s how main character TifAni FaNelli’s voice was born. Someone angry, desperate to succeed in order to distract from or make up for her past. The story becomes about the way in which a violent crime can live with someone fifteen years later. How it changes them, develops them, becomes part of them.

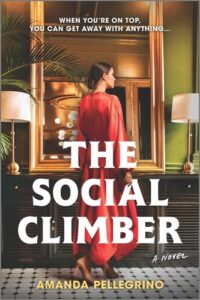

I felt the same way when I was writing my sophomore novel, The Social Climber. The book follows Eliza Bennet the week of her wedding, when secrets from her past attendance at an Evangelical college start to throw her true motives into question.

I had always been fascinated by hyper-religious, Megachurch universities. The college experience, for me, was a period of pseudo-freedom; the stakes were relatively low in terms of how much bad a natural rule-follower like me could do, but I was able to dip my toe into a subdued version of adulthood. A purgatory-like temporary middle ground where I lived with friends and made decisions for myself with limited guidelines or supervision. It was a time to start exploring who you are when there’s no one there to tell you what to do or who to be.

The extreme Christian colleges in my research, however, operated differently. Liberty University—the largest Christian University in the world— was my most prominent researched example, with Oral Roberts University and Bob Jones University coming in a close second. These schools had rules. Strict ones. About dress codes and visitors; friendships and relationships. They established curfews and mandatory rituals. I wanted to explore what happens when a person seeking freedom—thinking college was their means to get it—instead had it restricted. I wondered what it would be like to seek freedom elsewhere—what kind of trouble would someone get into when every decision they make is regulated. It made me think of the restriction to binge pipeline I’d become familiar with in regards to eating disorders. If you restrict, restrict, restrict… eventually, it’s common to binge. If you’re controlled, controlled, controlled… eventually, do you rebel?

I had that question in the back of my mind while thinking about the theme of the book—what message did I want to send, what point did I want to make?

That’s when I started thinking about Chanel Miller. In 2015 she was sexually assaulted on Stanford University’s campus by Brock Turner. Turner was convicted of three counts of sexual assault, sentenced to six months in jail, and served three before being released on good behavior. A discussion that came out of the case was about privilege and the handling of college sexual assault.

If schools are generally underreporting sexual assault—one study proports “the actual rate of sexual assault is at least an estimated 44% higher than the numbers that universities submit in compliance with the Clery Act”—what would happen in a school that also has extremely strict abstinence policies? A school like Liberty University, or Oral Roberts University, or Bob Jones University.

In July 2021, a dozen anonymous former students from Liberty University sued the school and came forward alleging a pattern of school officials “discouraging, dismissing, and even blaming female students who have tried to come forward with claims of sexual assault.” The lawsuit claimed, “the school failed to help victims of sexual assault and that the school’s student honor code made assault more likely by making it ‘difficult or impossible’ for students to report sexual violence.”

For me, the key to writing about this—to exploring how privilege and age-old rules aid in the mishandling of sexual assault reports on college campuses—was to not write it at all. The Social Climber does not feature a graphic assault scene. Instead, it features Eliza Bennet, reeling from her past, determined to make it right. It features a character who feels angry and betrayed, who needs to overcome this in order to move on. She needs to feel in control because so much of her past was defined by a lack of autonomy, a lack of self. A lack of liberty.

As an adult, Eliza has meticulously climbed the social ladder from religious cult upbringing to Upper East Side elite. She has the gorgeous old-money fiancé, the upper-crust penthouse apartment, the glossy job. She’s made it in a city that never would have accepted the old her. In fact, the old her never would have tried. It’s through her sharp observations of the privileged world of the one-percenters she’s surrounded herself with that we’re able to begin to understand how people like Brock Turner or any of the dozen men who assaulted the women of the Liberty University lawsuit can be protected.

They say show, don’t tell, and I think that especially applies to fictionalizing true crime. Don’t preach the point you’re trying to make or list the crime elements you’re trying to highlight. Write a compelling character that readers will invest in, and experience everything through her eyes. Let your character’s actions, reactions, behaviors, and emotions start the conversation about what you’re trying to say.

***