As my dad tells it, he was a third-year graduate student in Lubbock, Texas (my birthplace) interviewing a candidate for a faculty position. The candidate: a woman from Pennsylvania. The setting: not Pennsylvania—with Lubbock’s two-dimensional landscape, a blue sky stretched out until it is cellophane thin, and a deep deep dark come a moonless night. Not long into the interview, the woman paused before asking my dad: How are you not afraid to live out here? You can see everything.

She’s right—you can see everything in west Texas, just like you can see everything if you stand in the middle of some stark open plain across much of the West. And while I can’t know the source of that woman’s fear, I understand how such an environment diminishes and denudes you with its sheer vastness, its over-exposure. That emptiness (of body and geography) equates to fear—a raw fear that burrows into your mind, your heart, where the unknown and the to-come are surely violent and visceral ends.

Out of this emptiness, the Western was born. And then that genre was filled with gunfights and party raids, bear attacks and buffalo stampedes, murder, rape, theft, insanity, etc.

Writers have long painted the West (particularly the Old West) with a blood-stained brush. The violence takes different forms—physical (No Country for Old Men), mental (The Homesman), environmental (The Revenant: A Novel of Revenge), cultural (“Brokeback Mountain”)—and often a mix of them. Regardless of form, each of these narratives offers a big-blue-sky lesson: Bad shit happens out here.

In No Country for Old Men, the Texas-Mexican border is a hard-baked, lawless space where modernity and history collide, and then each of them subsequently bleed to death. The novel’s setting and events are less mythical than in many of McCarthy’s other texts, which sharpens the violence by making it more literal. Basically, men of different ilk find different ways to shoot or be shot at, all over a briefcase full of money. In The Revenant: A Novel of Revenge, a party of fur trappers navigate Native Americans and the environment until their commerce dissolves with a bear attack, after which human indifference/cruelty reduces men to their baser instincts. The Homesman is a sad but crucial look at the psychological and physical trauma of isolation and abuse—particularly on women—among the frontier. And then there’s the cultural reckoning of the West (hypermasculinity, whiteness, poverty, straightness), of which “Brokeback Mountain” explores and for which violence, in both fiction and fact, is the arbiter of existence.

Established writers such as Cormac McCarthy, Annie Proulx and Larry McMurtry have spent decades teaching us that in that wide-yawning space, there exists a singular degradation of our humanity. And then there are the newer writers, such as Tom Lin and C Pam Zhang. They carry the Western genre into a new era of diversity and story, but violence remains a core feature, even a transformative one.

Both The Thousand Crimes of Ming Tsu and How Much of These Hills Is Gold use violence to expand notions of identity in the Western. They illuminate the ways historic invisibility—the persistent conflation of Ming (our protagonist assassin) with other Chinese characters by white characters, Sam’s transgender identity—is both the result of violence and a weapon in itself. “How can the Western do more, see more, be more?” is perhaps a more recent question posed by contemporary literary Westerns such as these—and an essential one. But the tools for that question’s construction are the same: blood and guns and death and self-searching and more blood.

In fact, as hard as I try, I can’t think of a Western (past or contemporary) without violence. (Reader, please let me know if I’m wrong about that.) All of which suggests that violence is as integral to the genre as the landscape. So much so that you casually mention to someone that you’re writing a Western and you’ll see the gun flash in their eyes. Which ultimately leads me to wonder: Could someone write a Western without violence?

Sure, but they shouldn’t.

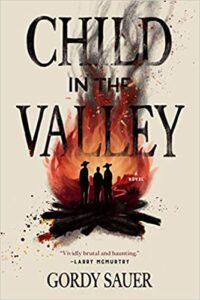

When I began writing my novel, Child in the Valley, I knew two things: 1) I wanted to reimagine the Western, and 2) I wanted to focus on an “anti-hero” main character. Violence was a major factor driving both objectives. While my main character, Joshua Gaines, is someone readers are sympathetic to early in the book (he’s born into poverty, he’s orphaned twice in the span of 17 years, he endures deep discrimination given his sexuality), his journey—or rather, his descent—into a murdering, marauding, thieving young man poses an existential question: What does it mean for someone to belong in this country?

Joshua doesn’t feel like he belongs. Not in his St. Louis home with his adopted father; not in his impoverished life; not among the society and culture in which he was born. His whole, tragic journey is a journey of belonging. It’s a journey I felt I could only undertake in a Western narrative. Because unlike other genres such as the noir or the thriller—where violence is often siphoned through an individual killer (or killers) and given a certain face with certain traits—violence in the Western is viral. It hangs in the air, capable of infecting anyone (hence, Joshua), all the while revealing how fragile our sense of humanity and community can become when the threat of unbelonging is as broad as the land.

So no, someone shouldn’t write a Western without violence. Seeding the genre with violence means our stories haven’t stopped interrogating what it means to belong. It means we’re not blind to the very real violence of the West that is the consequence of (or the retribution for) unbelonging: the forced removal of Indigenous peoples, the erasure of historical context, the unbridled expansion into sensitive environments. With that violence on the page, we don’t have to be afraid of a depthless landscape—precisely because we can see everything.

***