Early in my career as a novelist, I received a critical review of my work complaining that I described, in too much detail, the garments worn by my characters. It may have been fair comment. I was in my twenties at the time, a debut crime novelist. My writing instinct was correct, though, if perhaps not my delivery, and twelve books later, I’d like to explain why:

Furnishing the reader with details of the appearance of characters, and perhaps especially their clothes, makes good storytelling sense. More even than the shape of a face, or a glint in the eye, the cut, quality and state of a character’s garments, their footwear, the state of a suit and the quality of a piece of jewellery reveal important details about the history, social class, financial position, personality and in some cases intent of a character. As a mid-century vintage nerd, occasional dressmaker and former fashion model I am well placed on the details of garments, with my interest being particularly focussed on the time period I am currently writing about—post-WWII—so it is entirely appropriate that I have given my new 1946 PI heroine Billie Walker a keen eye for seams and collars, brooches and brogues. But before you disregard this attention to detail as the skewed interest of a female writer, as that early reviewer did, I’d like to point out that this descriptive technique has form with one Raymond Chandler, creator of one that most enduring and observant character, Phillip Marlowe—not a fashion victim but a hardboiled PI. Chandler’s novels are filled with detailed descriptions of bouncers in pink suspenders, authors in white flannel suits and violet scarves, and even speculation on the fashion choices of a man who furnished an office: “The fellow who decorated that room was not a man to let colors scare him. He probably wore a pimento shirt, mulberry slacks, zebra shoes, and vermilion drawers with his initials on them in a nice Mandarin orange.”

Just feast your eyes on this sartorially splendid scene from The Long Goodbye:

“She was slim and quite tall in a white linen tailormade with a black and white polka-dotted scarf around her throat. Her hair was the pale gold of a fairy princess. There was a small hat on it into which the pale gold hair nestled like a bird in its nest. Her eyes were cornflower blue, a rare color, and the lashes were long and almost too pale. She reached the table across the way and was pulling off a white gauntleted glove and the old waiter had the table pulled out in a way no waiter ever will pull a table out for me…”

Marlowe (and his creator) notice the clothes, the hairstyle, the gloves and what they signal about the person wearing them. This is no mere description, not simply the delightful painting of an aesthetic picture, but a type of cheat sheet for every character Marlowe encounters. It’s true that in hard-boiled we are accustomed to descriptions of hard men and femme fatales with faces like angels, but the clothing takes us a necessary step further. Without nuance and purpose the whole exercise falls too quickly into cliché, but the sartorial observances of Marlowe are meaningful. They are the mental notes of a seasoned private investigator, a man well versed in human behavior, in social mores, in lies, coverups and the meanings imbedded in clothes. These details matter. Tailormade means something quite different to off-the-rack. White gauntleted gloves are code for wealth, and the untouched and untouchable. It’s not only the garments we must pay attention to, but also the condition. Well-cared-for clothes speak to hired help or fastidious personal grooming, or both. Anyone who studies crime as I have for two decades or has seen more than a few court rooms will note the threadbare clothes, or badly fitting suits borrowed for a court appearance. Marlowe knows this, too. In fact, despite famous lines like “I like smooth shiny girls, hardboiled and loaded with sin,” the details of menswear rate at least as much mention as womenswear in Marlowe’s world, as we see from this scene in Farewell, My Lovely:

“He was worth looking at. He wore a shaggy borsalino hat, a rough gray sports coat with white golf balls on it for buttons, a brown shirt, a yellow tie, pleated gray flannel slacks and alligator shoes with white explosions on the toes. From his outer breast pocket cascaded a show handkerchief of the same brilliant yellow as his tie. There were a couple of colored feathers tucked into the band of his hat, but he didn’t really need them. Even on Central Avenue, not the quietest dressed street in the world, he looked about as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel food.”

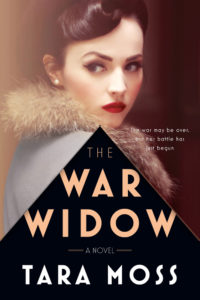

In The War Widow, my central protagonist is a Nazi-hunting war reporter returned home to Sydney to find she is not wanted by the local newsrooms, who are prioritising returned servicemen and encouraging women to ‘get back in the kitchen’. Determined not to rely on any man, she reopens her late father’s agency and sets up as a private inquiry agent. (Unlike the private dicks of the American-noir tradition, Australian PIs were prevented by law from using the term ‘detective’ regarding their trade.)

Like any good PI, Billie Walker uses clothes strategically, to hide a concealed weapon, to stand out or shrink back in a room, to slide convincingly into the glamourous, high end of town, or the usual rough dosshouses and dives. In a pinch, she’ll use a hat pin as a weapon, or a silk slip to wipe prints. Her clothes speak to the period, as does the fact she mends and sews them herself as rationing in the 1940s required, but that isn’t to say they always go unscathed, for instance when a visit to a classy but suspicious establishment ends in an unexpected skirmish on the street outside, an armed attacker grabbing her from behind:

“Seizing the man’s left leg, she wrenched it forcefully off the ground, pulling up and forward, cradling his foot to her chest. She heard a seam of her carefully sewn dress tear, followed by the more satisfying sound of her attacker falling backward with an awkward thrashing movement. She leaped out of the way, letting go and momentarily free before a second assailant grabbed at her leg and she went down on one knee, feeling a stocking tear irreparably. Now she was cross. Very cross indeed.”

Those stockings were expensive things in the 1940s. Darned expensive.

As in the richly detailed world of Phillip Marlowe, Billie Walker’s fine knowledge of dress reveals clues about the characters she encounters, like this introduction to her future client Mrs Brown:

“Billie took her appearance in quickly: she stood roughly five foot three and wore an impressive chocolate‐brown fur stole clasped at the bust, probably mink or musquash, and fine quality at that. Beneath that was a brown suit of a light summer weight, a little drab and conservative in its design. Probably tailor‐made, but not recently. Her Peter Pan hat was prewar in style, not the latest fashion… but her fur . . . now, that was special, almost out of place on a person like this.”

The pre-war hat, and indeed the shining fur stole speak to Mrs Brown’s material circumstances, employment and family influences, in much the same way Billie’s mother, Ella von Hooft’s fading Schiaparelli wardrobe—the couture of a 1920s aristocrat—speaks to her moneyed origins as well as her falling fortunes by the time the events of the novel unfold. Every dress, every suit, every object in The War Widow tells a story. As Billie Walker finds herself pulled into Sydney’s dark underworld on a case to find Mrs Brown’s missing son, taking her from glamorous night clubs and auction houses to seedy and violent back alleys, each character she encounters reveals themselves not only through action, but through the language of clothing.

In the world of the investigator, or indeed the novelist, disregarding dress is not something you can afford. We may use clothing to try to enhance or disguise our class, our bodies or our motives. We may use clothing to broadcast that we belong, or that we do not. Our clothes may betray us or propel us to success, but make no mistake, they never simply cover us. Clothing is never neutral.

In Marlowe’s world, clothes don’t so much maketh the man as reveal him.

He’s not wrong.

***