These are exciting times for crime fiction enthusiasts, especially those in search of narratives that feature previously marginalized voices. An article by John Fram in the New York Times recently noted that diverse authors, including S.A. Cosby, Rachel Howzell Hall, Richie Narvaez, and Steph Cha, are writing outstanding novels that “depict the failures of the criminal justice system or center the experiences of nonwhite protagonists.” No Native American crime writers were mentioned in the article, but just two months after that op-ed appeared, another article was published in the New York Times describing how Native American authors are reshaping the genres of science fiction, fantasy, and horror. The piece, written by Alexandra Alter, noted that, “Their fiction often draws on Native American and First Nations mythology and narrative traditions in ways that upend stereotypes about Indigenous literature and cultures.” This deserved celebration of Native writers working in the genres of horror, fantasy, and speculative fiction raises the question of whether the genre of crime fiction might also be energized by indigenous authors, who are not only writing gripping narratives, but investigating questions of colonization and sovereignty in their works.

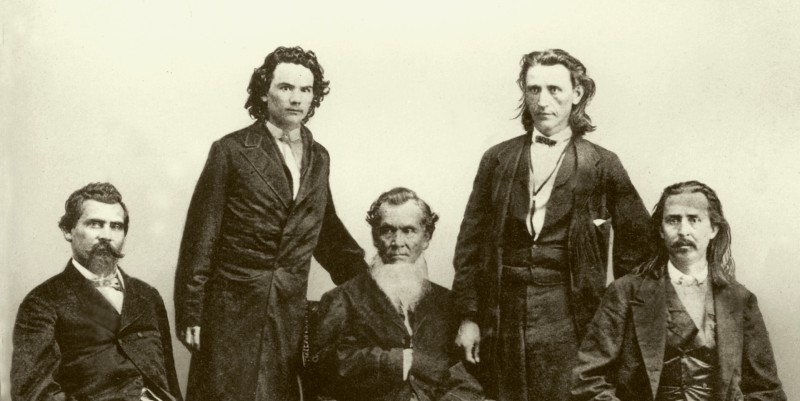

If asked about Native American mystery novels, the typical crime fiction fan will almost certainly mention non-Native writers such as Tony Hillerman, James Doss, Thomas Perry, and others. However, Native-authored crime fiction has a long history, if not always a great deal of visibility. The first novel ever written by an indigenous author is The Life and Adventures of Joaquín Murieta (1854), by the Cherokee writer John Rollin Ridge. In the 1930s, the Choctaw writer Todd Downing wrote a series of detective novels, although they didn’t take place on Native lands or feature indigenous characters. More recently, the Chickasaw author Linda Hogan published Mean Spirit (1990), the tale of the Osage murders in the 1920s and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. During the 1990s and early 2000s, some of the most important work in Native-authored crime fiction was published. Louis Owens (Choctaw-Cherokee), perhaps the most significant indigenous crime writer in the United States, wrote a series of award-winning novels, including Bone Game (1996) and Nightland (1996). Other Native writers, including Carole LaFavor (Ojibwe), Mardi Oakley Medawar (Cherokee), Sara Sue Hokklotubbe (Cherokee), and Stephen Graham Jones (Blackfeet) published notable mystery and suspense novels. In the 2010s, Linda Rodriguez (Cherokee), Tom Holm (Creek/Cherokee), Joseph Bruchac (Abenaki), and most notably Marcie Rendon (White Earth Nation) published important Native crime novels.

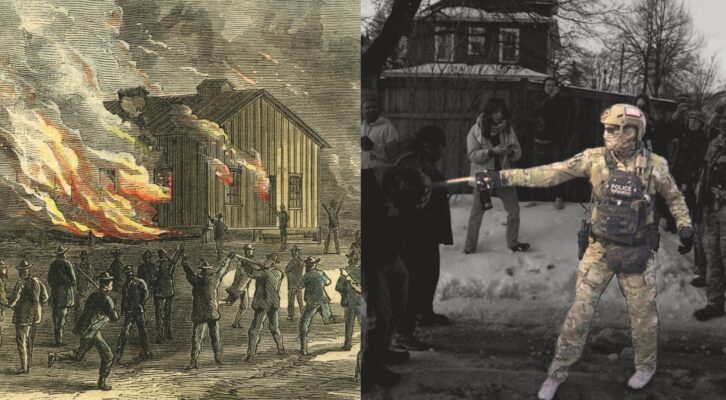

Despite these excellent books, it is undeniable that crime literature written by Native authors remains less well known among mystery and suspense fans. But I’ll argue that indigenous crime fiction matters—especially during these times of political and cultural upheaval. Native literature is especially needed now, as political and legal norms are being rapidly challenged. Indigenous crime fiction can serve to inform non-Native readers about little known inequities on reservations and in urban areas as well as serve as a commentary on the effects of colonization on Native peoples. Crime fiction is uniquely suited to serve as a call to action for examining structural inequalities affecting Native citizens in the American political system.

I teach Native American Studies at the college level, and I’ve discovered that the overwhelming majority of students are almost completely unaware of the history of Native Americans in the United States. They are astonished when they learn about the policies enacted by the government regarding Native people. For example, they are stunned to learn that Native spirituality was criminalized in the United States until 1978, despite the supposed guarantee of freedom of religion in the First Amendment. Most are unaware that, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an estimated forty percent of Native children were taken away from their parents without consent and educated at boarding schools, where they were stripped of their cultural identity and frequently abused. They are surprised to discover that Native Americans weren’t granted voting rights until 1924, and even after that date, many Western states prevented indigenous citizens from exercising their right to vote in state and federal elections.

My recently published novel, Winter Counts, examines the effects of the Major Crimes Act of 1885—which is still the law of the land—and how it prevents Native nations from prosecuting violent felony crimes that occur on their own territory. Instead, Native law enforcement officials must refer these felony cases to federal authorities, who decline to prosecute a large percentage of these cases, resulting in the offenders being released. My recent essay in the New York Times discusses this issue in more detail. Winter Counts also makes reference to the frequently substandard health care provided to Native Americans on reservations, the housing crisis there, and the problem of providing access to healthy and sustainable foods. All of these legal and political issues are the direct result of the effects of colonization of Native lands and people, and the failure of the U.S. government to adhere to the terms of the hundreds of treaties that were made and then broken, repeatedly.

But Native crime literature should not be viewed as simply a polemic against historical abuses and current inequalities. Indigenous authors are writing great literature that not only entertains, but provides a window into the Native worldview. For example, the works of Louis Owens, Louise Erdrich, and Marcie Rendon show us the resilience, joy, and humor of Native people without resorting to the stereotypes that are too often employed in some narratives.

Indigenous crime fiction matters. At its best, it informs and entertains, while also incorporating a transgressive style and content, creating awareness of political and structural inequalities. This is in contrast to the standard model of crime fiction, which often involves a detective investigating and solving a mystery: justice is served and equilibrium is returned to society. But Natives know all too well that wrongdoers are not always caught, and justice is not always restored. The best crime fiction today not only presents the alternative viewpoints of previously marginalized groups, it illustrates the problems inherent in the political and justice systems. This work can—hopefully—contribute to the dialogue about racial justice that’s now occurring across the nation.

—Featured image, Cherokee men negotiating treaty, author John Rollin Ridge far left.