We live in age of “genre-bending” books. Every other novel of the shelf seems to offer up some new combination: coming-of-age zombie novel, Western space opera, postmodern horror, Gothic fantasy. And that’s just as it should be. Literature stays vital through the constant recombining, reconfiguring, and reinvention of styles and forms. But out of all these different mixtures, there’s one pair that seems especially potent: science fiction and noir.

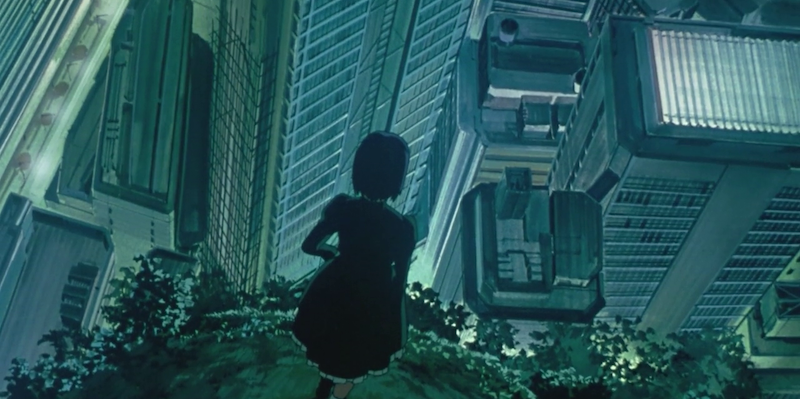

The mixing of SF with noir and hardboiled fiction dates back to at least Philip K. Dick’s classic 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (the basis for the film Blade Runner, which leans even more heavily into the noir tradition) and runs up through, well, the recent sequel film Blade Runner 2049. Between those are a host of fantastic science fiction works that draw upon noir themes and hardboiled language. William Gibson’s 1984 cyberpunk masterpiece Neuromancer. Masamune Shirow’s 1989 manga Ghost in the Shell. Kathryn Bigelow’s 1995 film Strange Days. Lauren Beukes’s 2010 novel Zoo City. The list goes on and on.

My own novel, The Body Scout, which was published on September 21st by Orbit, follows in this tradition. It features an out-of-date and underemployed cyborg baseball scout for a future sports league run by biotech and pharmaceutical corporations. There’s a murder mystery, of course, as well as fun and weird elements like philosophical Neanderthals, genetically edited CEOs, and cybernetic loan sharks. When I was writing the novel, I was just following my interests as someone who grew up reading Raymond Chandler alongside Ursula K. Le Guin. But having finished the book I’ve been wondering, why do the two genres fit so well together? Why is it a match you see made year after year, decade after decade?

I think the answer lies first in the fact that both genres have an inherent critique of the social order. They question the state of the world, refusing to just accept the corruption, inequality, and destruction as “the way things are.” Or at least saying, sure, it’s the way things are, but it’s still screwed up.

While other crime genres are often fundamentally a defense of the status quo—police procedurals focus on petty criminals and heroic cops, spy thrillers defeat threats to the established global order—noir presents the established order as crime. It is the rich and the powerful, and the institutions that serve them, that are the true villains. (Of course this isn’t true of every single noir work, but it is of the ones that influenced SF subgenres like cyberpunk.) Take Dashiell Hammett’s masterpiece Red Harvest, in which a rich man and a corrupt police force collaborate with gangs to crush poor workers. Or Chinatown, in which a business tycoon controls government institutions to choke off water supplies. This critique of the social order is why the prototypical hardboiled (anti)hero exists outside of the official law enforcement structure. They’re not a police officer, FBI agent, or government spy. They’re a private investigator, and sometimes even unlicensed as in the case of Walter Mosley’s Easy Rawlins, and realize that the legal system is as corrupt as the organized crime it is fighting…and often in bed with.

Science fiction too offers a critique of the established order by its very nature. Whether it’s set decades or thousands of years in the future, science fiction is necessarily a commentary on the way things are now. Orwell was writing of the corrupt governments of his time in 1984. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness comments on gender roles in our world. Science fiction’s dystopias imply problems in our current way of life, and its utopias offer possibilities of different ways of living.

This blending of science fiction with noir and hardboiled tropes is often reduced to “cyberpunk,” although it’s quite possible to blend the two without the “cyber” focus of hackers, AI, and virtual reality. Take Jonathan Lethem’s 1994 excellent debut novel Gun, With Occasional Music, that marries a Chandleresque private eye in a future filled with “evolved” talking animals and cryogenic prison sentences. (My novel, The Body Scout, is an attempt to replace the “cyber” in cyberpunk with flesh and look at what happens when the human body becomes the major realm of technological innovation and corporate control.)

Noir and its hybrids seem to flourish in times when we realize the problems we face infect society from top to bottom. Hardboiled fiction was born in the Great Depression and flourished (along with film noir) during the next decades of corruption and global war. Cyberpunk was born in the 70s and 80s when the threat of nuclear annihilation hung over a society that fought alienation with empty corporate consumerism.

Today, I think we’re seeing the start of a resurgence as climate change threatens every aspect of human life even, political alienation is heightened, and billionaires horde more and more wealth so they can see who can first colonize space for profit. These days, the greatest dystopian novel might be the evening news. And so noir and science fiction remain a match made in heaven or, perhaps more accurately, a match made in our current hellscape.

But perhaps to stave off my own fear of what seems to be our hopelessly apocalyptic future, I’d like to think there is another reason science fiction and noir pair well. And that’s, I suppose, hope.

In 2014 when Ursula K. Le Guin won a National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, she said, “We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.” This was a call, I think, especially to science fiction writers. What better art is there to give us a vision of a future way of living than the one genre dedicated to the future?

What science fiction can add to noir is a vision of another way of life. Noir provides the critique, and science fiction the possibility of change. Perhaps this vision only occurs as glimpses, especially when we’re talking SF noir. (A noir can never be truly utopian.) But a SF noir can give us hope in glimpses. In streaks, like UFOs speeding across the night sky. But it’s there. A little bit of light in the dark.

***