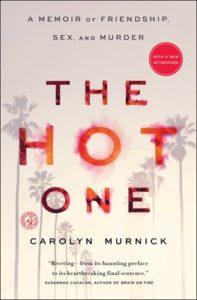

The true crime renaissance has been in full effect for several years now. Just look at the popularity of Netflix series like Making a Murderer and The Keepers, podcasts Serial and My Favorite Murder, and nonfiction such as I’ll Be Gone in the Dark by the late Michelle McNamara and The Hot One: a Memoir of Friendship, Sex & Murder by Carolyn Murnick (MFM hosts Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark have also just published a new book, titled after their signature sign-off phrase, Stay Sexy & Don’t Get Murdered).

What do all of these pop cultural products have in common? They are each by, about, and (for the most part) for women, the primary audience for the true crime genre.

The gender breakdown for listeners of true crime podcasts routinely hovers around 80% women, while Richard A. Marini reports at the San Antonio Express-News that 60% of new podcast hosts on the Murder.ly network are women. Though Netflix doesn’t divulge its ratings or audience gender ratio, Statistica offers that 75% of female respondents to a February 2017 survey have a subscription to the streaming platform. And we know women read more books than men, so it only makes sense that the true crime audio and visual boom would infiltrate the literature world.

What do all of these pop cultural products have in common? They are each by, about, and (for the most part) for women, the primary audience for the true crime genre.This is nothing new, of course. Women have been writing about crime for a least a century. Hardstark, one half of the podcast–author team behind the abovementioned My Favorite Murder and its companion compendium Stay Sexy & Don’t Get Murdered, writes about her obsession with true crime from a young age, namechecking Ann Rule’s 1980 memoir about having known Ted Bundy as pivotal in her journey to becoming a “Murderino” (fan of the podcast and true crime more broadly).

Hardstark and co-author/host Kilgariff follow in Rule’s footsteps by injecting their personal experiences into their true crime chronicles. Their informal and friendly tone as they write about tools that readers can use to keep themselves safe, such as “fuck politeness,” “get a job,” and “buy your own stuff” (no doubt inspired by the fuck off fund), which in turn make up their chapter titles, mirror the spirit of the podcast. The title, then, is a bit misleading but it takes its name from their sign-off catchphrase so it only seems fitting.

My Favorite Murder hosts Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark

My Favorite Murder hosts Karen Kilgariff and Georgia Hardstark

Anyone familiar with the podcast will recall criticism that the hosts, with their background in comedy not victims advocacy or investigation, were insensitive and, at times, victim-blamey. Kilgariff and Hardstark acknowledge this and write how their own experiences with lecherous men and, you know, living in a patriarchal world may have colored their initial reactions to female victims of homicide.

Another true crime-memoir hybrid that paints an at-times-ugly portrait of the author’s biases as she reckons with the 2001 murder of her childhood friend is The Hot One by The Cut reporter Carolyn Murnick. Published in 2017, The Hot One will likely ring a bell as the trial of Ashley Ellerin’s murderer, known as the Hollywood Ripper, is underway with Ashton Kutcher—who was dating Ellerin at the time of her death at the age of 22—as a star witness.

Throughout the almost two-decade ordeal, Murnick reckons with the long-held “stereotype of the good girl gone bad, the ingenue eaten up by the great big seductive, manipulative, unforgiving city of Los Angeles.” (Coincidentally—or perhaps not given our culture’s obsession with murders from the underbelly of L.A., from The Black Dahlia to the Manson murders to Nicole Brown Simpson—all three books discussed here are set in or around the City of Angels.) Murnick peppers her manuscript with sometimes brutal honesty – she acknowledges how feelings of anger, judgement, and resentment fractured her friendship with the eponymous Hot One prior to her murder. Over the course of the memoir, Murnick’s jealousy at the constant male attention her friend receives evolves into empathy for the exhaustion Ellerin likely felt at having to always be “on” for men, from admirers in the club to those with whom she engaged in sex work. Murnick writes with a growing disdain about the men who chewed up and spat out Ellerin and, by extension, all women, as she attempts to makes sense of her former friend’s murder.

“[A]fter ten years of researching my friend’s murder, and almost 20 since her death, I can definitively say that her killer is the least compelling thing about her story. Her killer is simply a man. A boring, attention-hungry, deeply misogynistic cipher,” Murnick writes in a recent The Cut article about the serial killer renaissance. Far more interesting, both to Murnick and her readers, is the complex friendship between Murnick and Ellerin.

By the end of the memoir, Murnick is able to recognize Ellerin’s status as “The Hot One” as just another of the many arbitrary designations (the hot one, the smart one, the good girl) that inform how men treat us. The authors of Stay Sexy and Don’t Get Murdered make a similar acknowledgment—“We run around making ourselves miserable and insane trying to be the Best One, when we should really be aiming to become Our True Selves,” Kilgariff writes. This is from a part of the book that’s more self-helpy, (in fact Kilgariff confesses that this line comes from her therapist) and represents, in a nutshell, Hardstark and Kilgariff’s signature blend of true crime mixed with self-advocacy. Living a lie won’t make you happy—and no amount of appealing to the aforementioned categories will prevent violent crime. Murderers gonna murder.

Though the late Michelle McNamara, in I’ll Be Gone in the Dark, does not have as intimate a connection to the subject of her investigation as the other authors discussed here, there is an undeniable personal connection and narrative running through the author’s quest to identify the Golden State Killer, captured soon after the book’s publication in the wake of McNamara’s untimely death in 2016. Like the MFM women, McNamara writes of her childhood interest in true crime, having grown up in in the shadow of a young woman’s unsolved murder in the suburbs of Chicago.

“I love reading true crime, but I’ve always been aware of the fact that, as a reader, I am actively choosing to be a consumer of someone else’s tragedy,” she writes. “So like any responsible consumer, I try to be careful in the choices I make. I read only the best: writers who are dogged, insightful, and humane.” One could surmise that McNamara’s own writing could be described using these words.

By bearing witness to these women’s murders, we in turn bear witness to their lives before they were tragically cut short.One could also posit that the way these authors position the murders they write about as integral to the formation of their personalities and lives is a key audience driver. Regardless of whether it’s someone known to the author, as with Murnick, or an overarching true crime obsession stemming from childhood, like McNamara and Hardstark, these crimes are inextricable from women’s experiences because gendered violence is inextricable from women’s experiences. Conversely, McNamara’s meticulous and clinical narration of the Golden State Killer’s crimes proves that women don’t have to spill our proverbial guts to be successful crime writers. (And, notably, it proves that we can solve crimes.)

Previously victims of gendered violence suffered alone. If we were infamous enough to become a Nicole Brown Simpson, a Sharon Tate or, indeed, an Ashley Ellerin—notably all white and from well-off backgrounds—it was the men we were connected to; the male detectives and lawyers who narrated our trauma; and patriarchal news cycle and white man-fronted true crime genre telling our stories. Without Ellerin’s connection to Kutcher, it’s likely her murder would have been forgotten, like so many others, by virtue of her history in sex work. The accessibility of podcasts allows us to be able to tell our own stories; the expanding of the genre into Netflix and publishing means people are consuming these stories to a profitable level. And most of these people are women.

Murnick repeatedly uses the phrase “the bear witness” throughout The Hot One. “Somehow I still felt it was my obligation to properly bear witness to it all,” she writes. That’s in effect what Murnick, McNamara, Hardstark, Kilgariff and all of these books, podcasts, docos and, by extension, women’s obsession with true crime at large are doing. By bearing witness to these women’s murders, we in turn bear witness to their lives before they were tragically cut short.