“It is not good that the man should be alone.”

This line, from a well‑known Bible story, introduces into the narrative of our Judeo‑Christian heritage the most important element in story‑telling: trouble. From the fiction writer’s point-of-view, trouble is always the most interesting element in any story.

A writer looking at Genesis will notice something else, too—there are no concrete details of Adam’s blissful life in the Garden of Eden. The earth is created, Adam is placed in the garden, the beasts of the earth and the fowls of the air are created, and Adam names them. Then God perceives that his main character, his protagonist, is lonely, so God causes a deep sleep to fall upon Adam and extracts a woman from Adam’s rib. That’s when the Big Trouble starts. We all know the plot: there’s a snake, a tree, an apple, and some disagreement about what to eat under what circumstances. The trouble gets bigger. Adam and Eve are tossed out of the blissful garden into a world of toil and travail.

Two of their children are named Cain and Abel, and theirs is the first murder story. The two boys are specialists. Abel herds sheep and Cain tills the soil. They offer the Lord the products of their labor—a goat and some produce. The Lord, being, apparently, a carnivore, prefers Abel’s offering, and so begins the trouble between the brothers. “Cain was very wroth and his countenance fell.” Out in the field one day, Cain kills his brother. “And the Lord said unto Cain, `Where is Abel thy brother?'” Abel says he doesn’t know. “Am I my brother’s keeper?” A writer notices the word keeper. It is a word associated with livestock. A person doesn’t keep the fruit of the earth but does keep animals. Cain the farmer kills Abel the keeper of sheep. When Cain uses the word keeper, is he enjoying some sarcasm about the dead man’s occupation? An interesting footnote to this story appears in Genesis, chapter 4. Cain, the first murderer, is also the first man to build a city. He inaugurates social existence. Maybe it is Cain’s experience of trouble, of that most unspeakable of all forms of alienation, murder, that makes him able to understand the necessity for human community.

Trouble, conflict, lie at the heart of every good story. Bliss is boring.

Florida, where my own eight novels about trouble are set, is marketed as a state of bliss, but when you are in the state of bliss, your guard is down and trouble is not far off. Let me quote Gainesville writer, Al Burt, on the subject of Florida’s trouble: “Across [the state] there resonates a diminutive chord of unease, vibrations of the imbalance that occurs in the wake of answered dreams . . . Great swamps neighbor dune deserts, homes open up and bring the outdoors inside, extraordinarily benign winters flank peppery summers filled with rains and powerful thunderstorms, a population of strangers seeks home in exotic surroundings, and minority natives feel spiritually exiled in their birthplace . . . Condos worth $100 million and more go up within sight of tumbled‑down docks and rusting tin roofs.” When you live in a state of bliss, trouble can move in next door.

Trouble comes into fiction in the shape of a bad man or woman, a Cain looking for his Abel. A villain is the embodiment of evil. Perhaps paradoxically, it is easier to write villains than to write heroes. That is not to say that writers are looking for what is easy, but imagine yourself with this choice: You are an actor. You are offered the opportunity to play Hannibal Lector in The Silence of the Lambs or Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird. Which do you choose?

In an interview, the great actor Gregory Peck said that he had spent almost fifty years on stage and screen, playing good, decent, honorable men, and that it was a lot more difficult to do than most people supposed it was. He confessed to having experienced in the middle part of his career, a certain amount of boredom with goodness and decency. And then Peck was invited to play Captain Ahab. As mad, obsessed Ahab, Peck rides the back of the white whale, plunging a harpoon into the animal again and again. It was the turning point in Peck’s career. The moment when he broadened his repertoire of characters to include—a villain.

But what impressed me more than Peck as the complicatedly evil Ahab is the anger Peck brought to the screen when he played good, decent men. Watch Peck as Atticus Finch giving his courtroom summation in To Kill a Mockingbird and as Captain Keith Mallory in The Guns of Navarone. What the two performances have in common is Peck’s anger. Watching them, I realized that what we respond to in the hero who must face and defeat the villain is the hero’s potentiality for explosive anger. We wait for the moment when the good man is pushed too far. When his equanimity, his reserve are shattered and he breathes fire. This is not evil, it’s not villainy, but it is trouble, and seeing the second face of a decent man troubles the viewer. The good character walks in calm, believes in calm, but carries with him or her the possibility of the storm—of righteous violence. I believe it was Peck’s ability to project this potentiality that gave his calm and righteous characters a strange, edgy quality.

Writing a good villain is a way of shouting, a way of being heard over the babble of voices that is contemporary fiction.Writers, like actors, want to portray villains. We want to crawl into the skins of bad people, even though those skins may be slimy and infectious. Even though we fear we may become infected. Even though it may be difficult at times to climb back out again. The great Southern writer, Flannery O’Connor was asked why there was so much violence and grotesquery in her stories, she answered, “If you want to be heard, you have to shout.” Writing a good villain is a way of shouting, a way of being heard over the babble of voices that is contemporary fiction. I doubt that any of Thomas Harris’s decent and honorable characters would have gotten him noticed, much less have made his name a household word. The cannibal, Hannibal Lector, made Thomas Harris famous.

Places, too, are more interesting as villains. The Florida Dream is the deranged grandchild of that older dream, the one we call the American Dream: Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Florida dreams are about romantic escape, about a climate so mild that dreamers never awaken to sleet, rain, thunder, or flood. They are about a retirement that is long and prosperous and full of golf and early bird specials and saunas. The official slogan of the Florida tourist council in the 1980’s was, “The rules are different here.” But as we all know, dreamers are either asleep or daydreaming. In either case, they are half‑witted and vulnerable. Too often, in Florida, they wake up to some nightmare named Ted Bundy or Henry Lee Lucas or Eileen Wuornos.

Florida has often been called a Garden. (Cypress Gardens, Palm Beach Gardens, Busch Gardens come to mind.) It has been called Eden and Paradise and has been marketed as bliss, but when the newspapers are full of stories such as this one: “German tourist killed. Attackers shoot the cautious driver of a rented car on an expressway in Miami . . .” it isn’t long before somebody comes up with this headline: Florida: Paradise Lost. I would argue that Florida was never paradise. Not when Ponce de Leon came looking for the fountain of youth and named the place after the flowers he saw, not when General Gaines came to make war on Chief Osceola, not when Teddy Roosevelt stopped on his way to San Juan Hill, and not when William “Pig Iron” Kelly, a 19th century promoter, had this to say about the place: “We live on sweet potatoes and consumptive Yankees, but mostly we sell atmosphere.” Tuberculosis and a diet of sweet potatoes: Is it any wonder that the Florida writer’s story is the story of trouble in paradise and that writers needs villains to get the job done.

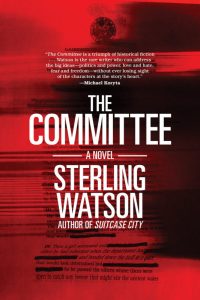

In my novel, The Committee, the serpent in the Florida garden is not an individual person but a group of men, The Johns Committee, who terrorize those they consider undesirable—homosexuals, communists, and the NAACP. They do their work with the imprimatur of the law and the government and in the name of their own definition of paradise. They were Florida’s bliss destroyers of their day. The man whose righteous anger comes awake will fight them. Will he gain or lose the Garden?