As a boy growing-up in the 1960s and ‘70s, my idea of science fiction usually revolved around alien invaders, fire breathing monsters destroying major cities or friendly Earth men exploring the galaxy before losing contact with home and crash-landing on some strange planet. My imagination was fueled by doses of DC comics, reruns of Flash Gordon/Buck Rogers serials on PBS and Godzilla Week on the 4:30 Movie. While I was an avid reader, my sci-fi/fantasy foundation was the many TV programs and films I devoured years before discovering the fictions of Robert A. Heinlein or Ray Bradbury.

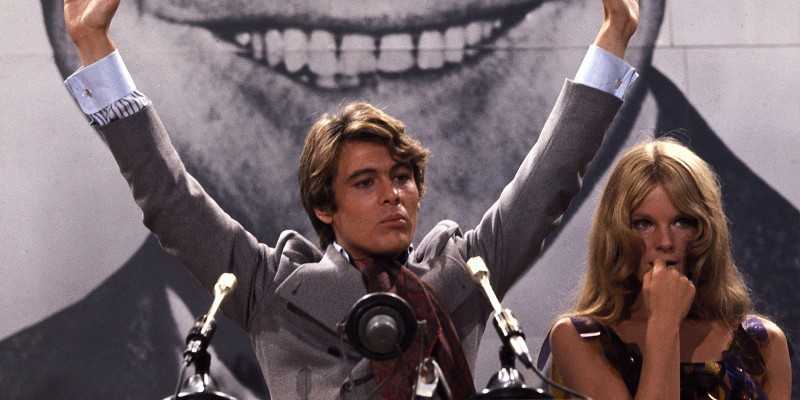

It was during one of my Saturday night movie marathons that I first saw the politically charged sci-fi satire Wild in the Streets (1968), a flick about a bugged-out alternative America guided by an insane pop star named Max Frost, his band mates The Troops and the millions of fans. Twenty-two-year-old Max despised anyone over 30, and throughout the film worked hard to get rid of mature adults who were “stiff with age.” Played with crazed charisma by method actor Christopher Jones, a southern mumbler who critics compared to James Dean, Max Frost began his mission by partnering with a youngish (thirty-seven years old) congressman who helped him by getting the voting age lowered to fourteen.

With the impressionable youth of the country already in Frost’s fat pockets (it’s established from the beginning that he’s a multi-millionaire who first made loot making and selling acid), he soon went power mad and preached that American kids “never trust anyone over 30.” Though Frost had zero experience as politician, his wealth and fame made him believable to the masses.

Using the powerful medium of television that had become a political tool a few years before when pretty boy John F. Kennedy debated ugly Richard Nixon in 1960, Frost’s message was basically “the younger, the better,” reasoning that older elected officials had lost touch with the real needs of the country. Without irony he declared, “I have nothing against our current President…that’s like running against my own grandfather. I mean, what do you ask a 60-year-old man? You ask him if he wants his wheelchair FACING the sun, or facing AWAY from the sun. But running the country? FORGET IT, babies!”

Later, he and the Troops spiked the water supply with LSD, held mass demonstrations on Sunset Boulevard, and encouraged his followers to storm the White House. Police fired on civilians, which created martyrs for Max’s corrupt cause. He’s helped by his acid head girlfriend Sally LeRoy (Diane Varsi), who believes Frost’s far-out philosophies. “America’s greatest contribution has been to teach the world that getting old is such a drag,” she says. “Youth is America’s secret weapon.”

At twenty-four she was elected to congress, worked to amend the laws of the land and paved the way for Frost to become president. Eventually, Max, who gave a few passionate speeches, but spent most of his time lounging in his mansion, became the youngest president ever elected.

Released in 1968, Wild in the Streets was directed by the underrated Barry Shear, who four years later made the neo-noir classic Across 110th Street. Wild didn’t take place in the past or future, but in crazed present day of the election year of 1968, mere months after the so-called “Summer of Love.” That same year America dealt with Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy’s assassinations, civil unrest in major cities, Nixon winning the Presidential election and a raging war in Vietnam that drove many young men mad and sent them home damaged.

“When I saw this movie, it changed my societal perspective completely,” recalled writer Bonz Malone. “Wild in the Streets is one of a kind. It’s even out of its own mind, but in a very smart way.”

A few years after its initial release, Wild in the Streets was shown on the ABC Saturday night movie which aired weekly at 11:30 pm. As a ten year old lying on the Banana Splits bed sheets staring at a black and white television set, I was completely fascinated by the film as I watched a once nice little boy (played with sweet innocence by pre-Brady Bunch Barry Williams) whose last name was Flatow, grew into a teen terror drug dealer, ran away from a shrill mother (played with annoying pizzazz by Shelly Winters) and a passive poppa who had no control over his family, changed his last name to Frost and became a pop star (he bought his first guitar from selling acid) before taking over the country.

Co-star Hal Holbrook played Congressman Johnny Fergus, who is running for the Senate with a campaign based on the promise of giving the vote to 18-year-olds. It was after inviting Frost to perform at a rally that the rock star decided to try politics. His lust for power, that included lowering the voting age to 14, opened the door for Frost’s ageist extremism that led to putting people over thirty-five into concentration camps and dosing them daily with LSD.

From the beginning, the real enemy was age; there was no such concept as “too young.” As Max proudly stated, “I don’t want to live to be 30…30 is death, baby.”

***

Actor Christopher Jones, who played the wealthy pop president, was born into poverty in 1941. A native of Jackson, Tennessee he’d had his share of hard times since childhood. His mother was institutionalized when Jones was a boy, and he spent time living at Boy’s Town with his younger brother. He ran away and enlisted in the Army when he was 16, went A.W.O.L. days later and soon fell in with an artsy crowd that guided him towards New York City and acting.

World Cinema Paradise contributor Peter Winkler wrote a brilliant essay on Jones in 2014 and cited a Quentin Tarantino interview from a 1999 episode of E! True Hollywood Story where the director said, “He (Jones) had excitement. He was a movie star. He looked like James Dean, but Chris Jones didn’t take himself seriously like James Dean. He had the same exact sensuality and appeal as Jim Morrison. He was a big comer at that point, as big as anybody!” The actor as Max Frost channeled a charming, yet disturbing persona that became scarier as the film progressed.

During my first viewing, the only actor I recognized was the boyish Richard Pryor in his first film role playing Stanley X. Despite the militant name and credentials (twenty-one, Black Muslim, anthropologist, drummer, author of Aborigine Cookbook), Stanley was just another cog in machine of Frost’s fame factory that led to eventual takeover of the country. For a Black Muslim, he doesn’t talk much, and, one of the few times he does, he encourages Frost to become a Republican and run on their ticket. No self-respecting Black Power rebel would’ve done that, which made me think Stanley X might’ve been a former Jack and Jill kid from the Midwest.

Late comedian Paul Mooney, who was Pryor’s best friend (he also wrote material with and for him) and hung out with him on set, claimed the comic got the role with help from Shelly Winters. In Mooney’s autobiography Black is the New White (2009) he wrote that Winters was allegedly, “one of the most cock hungry actresses in Hollywood… Richard is happy to pay the price of admission…they get wild in the sheets.” Co-star Larry Bishop (The Hook) told an interviewer that Pryor once appeared on set naked and freaked Winters out. Pryor also met his second wife Shelley R. Bonus, who was an extra in the movie.

Winters was also a friend of Christopher Jones’ and helped him with his career. Their closeness began with their association with the famed Actors Studio, where they both studied. Winters also, against her better judgment, introduced Jones to his first wife Susan Strasberg, daughter of their famed acting coach Lee Strasberg. She was also an actress and they were married for three years (1965–1968); their daughter Jennifer Robin was born in 1966.

Although Winters won an Oscar three years before, Wild in the Streets was the beginning of her long relationship with B-movie makers American International Pictures (AIP). The B-movie studio specialized in grindhouse/drive-in beach party, horror, science fiction and teen-exploitation flicks. Wild in the Streets fit in nicely beside their other crazed youth movies including The Wild Angels and Riot on Sunset Strip. Her later films with the company included Bloody Mama, Who Slew Auntie Roo and Cleopatra Jones.

In Wild, she played Daphne Flatow, the worst mother and wife on the planet. Though the character never wanted a baby and scolded Max often when he was a boy, she did become overly excited after seeing her him on television years after he deserted the family. “I’m somebody. I’m the mother of a famous man. I’m a celebrity!” she screamed. So desperate was she to be in her son’s limelight, after their reunion, it’s as though she’d forgotten that her precious baby boy had killed the dog and blown-up his father’s car before leaving home.

Daphne too started wilding out and even ran over an innocent kid while speeding in Max’s car. Of course, there were no repercussions and her behavior only became worse. “Ever since the accident, I’ve been under care of an LSD therapist and I understand my son now. I understand him completely.” None of this stops the age police from coming for her too. “No, no, no, I’m young! I’m young! I’m VERY young! I’m VERY YOUNG!” she screamed as they dragged her away.

***

Wild in the Streets was based on the Esquire short story “The Day It All Happened, Baby!” by Robert Thom, who also wrote the script. “Cool was on its way out,” the story began, swiftly moving on to Max’s “doomed parents” and the havoc he caused as a youngster. Thom, like Max, once had the surname Flatow, which he changed in college. Published in 1966, “The Day It All Happened, Baby!” was released at the beginning of the “new wave science fiction” movement when some younger authors began writing tales that featured issues that took place on Earth.

As noted in the award-winning Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950-1985, “This shift in focus was as much aesthetic as political. Influenced by modernist prose and poetry, William S. Burroughs and the Beats, New Journalism, psychedelics, and the quest for consciousness expansion became modes of expression more disjointed and experimental and topics shifted to the state of inner rather than outer space.”

Yale graduate, poet, playwright (The Minotaur, Bicycle Ride to Nevada) and screenwriter Robert Thom wasn’t as prolific in the short fiction department as J.G. Ballard, Barry Malzberg, Michael Moorcock or Harlan Ellison (who was a friend). Style wise, Thom was no match for those literary word slingers. “The Day It All Happened, Baby!”reads like a cross between a news piece for an underground newspaper and a movie treatment, but dude’s prophetic ideas in that single speculative story, as well as his screenplay for Death Race 2000 (1975), should be enough to gain him admission into the canon.

While Esquire didn’t publish much science fiction, editor Robert Brown, himself an alumnus of Yale, took a chance on Thom’s story. “We weren’t locked into any structure,” Brown recalled It Wasn’t Pretty, Folks, but Didn’t We Have Fun?: Esquire in the Sixties by Carol Polsgrove. “Mostly any magazine then and now, if you came up with some great idea, the editor would say, ‘That’s an interesting idea, but it’s not the sort of thing we do.’ At Esquire, there was no sort of thing we do.”

“The Day It All Happened, Baby!” was featured in the December, 1966 issue and predicted the soon come youth riots (1968 Democratic National Convention), musical mayhem (Altamont) and end of decade discord. Optioned a few months later by (AIP), Thom, who had written screenplays previously for young adult angst films All the Fine Young Cannibals and The Subterraneans (both released in 1960), was hired to do the script.

According to The History of Hollywood by Stephen Tropiano, the film was budgeted at $700,000, which for the penny pinching AIP was a kingly sum, and shot in 20 days. Apparently the studio had had another feature in production called Wild in the Streets that was shelved, so they changed the name of “The Day It All Happened, Baby!” so they could use the marketing artwork they’d already commissioned.

Originally the studio wanted to cast folk singer Phil Ochs to portray Max Frost, but the singer’s manager turned it down. “Arthur Gorson had disapproved of the movie’s right-wing message, and had discouraged Phil from accepting the part,” Michael Schumacher reported in There But for Fortune: The Life of Phil Ochs. “Twenty-five years after the fact, Michael Ochs still stewed about his brother’s rejecting the opportunity to star in the film.”

The role instead went to relative newcomer Jones, who had done theater in New York City and starred in the ABC western series The Legend of Jesse James (1965-1966), produced by Don Siegel. When the show was cancelled after one year, Jones made a smooth transition to the big screen. Jones’ evolution from funky folklore outlaw to smooth criminal rock star was seamless, with a few scenes highlighting the persuasive power of pop with the folksy “Fourteen Or Fight” and the more psychedelic “The Shape of Things to Come.” The lyrics for the latter were the perfect theme for a revolution: “There are changes lyin’ ahead in every road/And there are new thoughts ready and waitin’ to explode.”

Both songs, as well as others on the soundtrack, were written by Brill Building pioneers (wife & husband songwriting team) Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann, who had penned tracks for many artists including The Animals (“We Gotta Get Out of This Place”) and The Righteous Brothers (“You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin'”). Though the work of Weil and Mann was later used in many movies including An American Tale and A.I., Wild in the Streets was their first.

“The Shape of Things to Come” was released on Tower Records (not to be confused with the record store chain, the label was a subsidiary of Capitol Records) and credited to the 13th Floor aka Max Frost & The Troopers. Former Tower Records executive Mike Curb said in a 2010 interview with Forgotten Hits, “The reason we changed the name of The 13th Power to Max Frost & The Troopers was because the lead actor Christopher Jones played the role of Max Frost and we felt that we would have a better chance of breaking the record under the name of Max Frost & The Troopers. The record was a big hit and actually reached the 20s of the Billboard Hot 100 chart.”

Jones’ first three films-Chubasco, Wild in the Streets, and Three in the Attic—were all released in 1968. He later became known as a troubled actor who allegedly beat-up his first wife, raped his actress girlfriend Olivia Hussey and claimed to be having an affair with her friend Sharon Tate when she was murdered in 1969. That same year, he went overseas to make three European projects, with starring roles in Una breve stagione (1969), The Looking Glass War (1970), based on a John le Carré novel, and director David Lean’s film Ryan’s Daughter (1970). On the set of Ryan’s Daughter, Jones got a rep for being difficult to work with and was bad mouthed by the director and his co-stars, including Robert Mitchum and Sarah Miles.

Jones stepped away from acting and disappeared from the screen for thirty-six years. Some speculated that he had a nervous breakdown and became a drug addict after Sharon Tate’s brutal murder. Mental issues did run in his Jones’ family, with his mother being institutionalized when he was a boy. Quentin Tarantino wanted to cast him in Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994), but Jones never replied to his queries.

“I didn’t return Quentin’s calls because I didn’t know who he was,” Jones told the Chicago Tribune in the 2000 article Life After Fame, “and I wasn’t interested. When he did find me with the ‘Pulp Fiction’ script, I had no interest in acting or in the part he was offering.” “My girlfriend at the time read it and said: ‘You’re not doing this––it’s disgusting,’” he told another interviewer. Tarantino wanted him to play Zed. “So I didn’t.”

Jones later appeared in Mad Dog Time (1996) directed by Larry Bishop, a Wild in the Streets co-star who played one-handed horn player The Hook. The film opened to terrible reviews including Roger Ebert’s brilliant bombing: “’Mad Dog Time’ is the first movie I have seen that does not improve on the sight of a blank screen viewed for the same length of time. Oh, I’ve seen bad movies before. But they usually made me care about how bad they were. Watching ‘Mad Dog Time’ is like waiting for the bus in a city where you’re not sure they have a bus line.”

Granted, Ebert didn’t much care much for Wild in the Streets either, giving it two stars, but in that case he was in the minority.

As a contrast, New York Times reviewer Renata Adler wrote, “By far the best American film of the year so far––and this has been the worst year in a long time for, among other things, movies––is ‘Wild in the Streets.’ It is a very blunt, bitter, head-on but live and funny attack on the problem of the generations. And it is more straight and thorough about the times than any science fiction or horror movie in a while…It is a brutally witty and intelligent film.” Meanwhile, Pauline Kael liked it more than she did 2001: A Space Odyssey, which came out the same year. She called Wild in the Streets, “smart in a lot of ways that better made pictures aren’t.” Those sorts of reviews were rare for a studio like AIP as was the “blockbuster” status the film eventually achieved.

Decades later, critic John Greco from “Twenty Four Frames: Notes on Film” compared Max Frost, minus the ageism, to Donald Trump. In a 2016 essay, Greco wrote, “Wild in the Streets and its egotistical rock star are like our egotistical reality star of today, a frightening horror show all being played out with the potential to turn the country from the greatest democracy in the world into a totalitarian state filled with hate and fear.”

***

While some might view Wild in the Streets as silly, for others it was as powerful as It Can’t Happen Here, 1984 or Animal Farm. Though written as a cautionary tale, the ultimate message of Wild in the Streets wasn’t that “power corrupts,” but a democracy built on lies and bullshit shoveled to the gullible masses, whose blind faith keeps them from questioning The Truth, will eventually collapse into chaos. Thinking back to my ten year old self watching Wild in the Streets, I was riveted by the sheer daring of the entire film’s premise that, while being absurd, felt as though it could really happen.

In 1969, a sequel starring Christopher Jones and written by Robert Thom was supposed to go into production at AIP bearing the name The Day of the Micro-Boppers, which changed to “The Day It All Happened, Baby,” the title of the original Esquire story, and finally “We Outnumber You.” Unfortunately, the project never happened.

Thom later wrote a 15,800 word novella “Son of Wild in the Streets,” that was originally to be included in the infamous Harlan Ellison science fiction collection The Last Dangerous Visions. Though announced in the 1979, but the anthology was never published. J. Michael Straczynski, executor of the Harlan Ellison estate has taken over the project, but “Son of Wild in the Streets” is no longer included.

However, considering the film’s actual climax, it wasn’t too difficult to figure out where Thom was taking the story. Wild in the Streets ended ambiguously when, high on authority, Max Frost pisses off a group of kids after purposely killing their crawdad. One morally wounded kid looked into the camera and said, “We’re going to put everyone over ten out of business.”