Many who read this will have read Nightmare Alley. But it is to be hoped that others will be drawn to read this singular work for the first time. I envy the latter, and I don’t want to interfere with the experience that awaits them by delving into matters that would reveal its plot, which grows increasingly more powerful and bizarre from beginning to end. But, to paraphrase Ezra Pound, a little knowledge can do us no harm.

This book, first published in 1946, was born in the winter of late 1938 and early 1939, in a village near Valencia, where William Lindsay Gresham, one of the international volunteers who had come to defend the Republic in the lost cause of the Spanish Civil War, was awaiting repatriation. he waited and he drank with a man, Joseph Daniel Halliday, who told him of something that took him aback with a scare: a carny attraction called a geek, a drunkard driven so low that he would bite off the heads of chickens and snakes just to get the booze he needed. Bill Gresham was only twenty-nine then. as he would later tell it, “the story of the geek haunted me. Finally, to get rid of it, I had to write it out. The novel, of which it was the frame, seemed to horrify readers as much as the original story had horrified me.”

Upon his return from Spain, according to his own account, Gresham was not a well man. He became deeply involved in psychoanalysis, one of the many ways he sought throughout his life to banish his inner demons.

It was while writing Nightmare Alley that Gresham drifted away from psychoanalysis and became instead fascinated with the tarot, which he discovered while turning from Freud to, in the course of his research for Nightmare Alley, the Russian mystic P.D. Ouspensky (1878–1947).

Had only Gresham known of the paper Freud delivered at the Conference of the Central Committee of the International Psychoanalytical Association in September 1921. In it, Freud declared: “It no longer seems possible to brush aside the study of so-called occult facts; of things which seem to vouchsafe the real existence of psychic forces other than the known forces of the human and animal psyche, or which reveal mental faculties in which, until now, we did not believe.” Freud and Ouspensky then might have walked even more closely together down Gresham’s alley of nightmares.

Gresham used the tarot to structure his book. The tarot deck consists of twenty-two figured trump cards, of which twenty-one are numbered, and fifty-six cards divided into four suits of wands, cups, swords, and pentacles. The deck has been used for centuries for both gambling and fortune-telling. In the case of fortune-telling, it is the trump cards, also known as the major arcana, that are primarily employed, and these are the cards which give the titles to the chapters of Nightmare Alley. The first trump card is the Fool, which is the card that bears no number, and the final one is the world. Gresham begins his book with the Fool, but then shuffles the deck. his deck ends with the hanged man.

As piercing as the psychological probings of Nightmare Alley are, eerily the tarot alone is bestowed at times with a hint of ominous gravity and credence amid all the other spiritualist cons of the novel that are to Gresham and his characters nothing more than suckers’ rackets.

It is interesting, too, that while still undergoing psychotherapy, Gresham crafted in Nightmare Alley, in the somewhat heavy-handedly named character of Dr. Lilith Ritter, the most viciously evil psychologist in the history of literature.

He would later say of this time that six years of therapy had both saved him and failed him: “Even then I was not a well man, for neurosis had left an aftermath. during years of analysis, editorial work, and the strain of small children in small rooms, I had controlled anxieties by deadening them with alcohol.” He said, “I found that I could not stop drinking; I had become physically an alcoholic. And against alcoholism in this stage, Freud is powerless.”

Nothing worth reading was ever written by anyone who was drunk while writing it; but Nightmare Alley evinces every sign that its writing was binge-riddled. Booze is so strong an element in the novel that it can almost be said to be a character, an essential presence like Fates in ancient greek tragedy. The delirium tremens writhe and strike in this book like the snakes within. William Wordsworth’s dictum that poetry was “emotion recollected in tranquillity” here finds a counterpart in Gresham’s evocation in sobriety of what he calls in his novel “the horrors.”

Surely “the horrors” in this sense had been part of colloquial speech, at least among drunks and opiate addicts, before Robert Louis Stevenson used it in Treasure Island (1883), and it is still very much current today.

The matter of language is paramount here. Gresham’s cold blue steel prose is consummate, as is his use of slang in dialogue and interior monologue. never affected, always natural and effective.

As noted in a little profile of him published in The New York Times Book Review soon after the novel’s release: “Among the Gresham interests are confidence men, their wiles and argot, which he tosses off with a bland ease that, one executive at Rinehart was saying the other day, is enough to frighten an ordinary, law-abiding citizen.”

The word “geek” (derived from “geck,” a word for a fool, simpleton, or dupe, in use since from at least the early sixteenth through the nineteenth century) was generally unknown in its carnival sense of a “wild man” who bites the heads off live chickens or snakes, until Gresham introduced it to the general public in Nightmare Alley. In November 1947 the popular Nat “King” Cole Trio made a record called “The Geek.”

As an elaboration of “cinch,” the phrase “lead-pipe cinch,” to denote a sure thing, had been around since the nineteenth century, and it would stay around a good while more. It could be found in 1949 in Nelson Algren’s The Man with the Golden Arm and in 1974 in a New York Times financial report.

Some of the enchanting slang Gresham used seems to have appeared in print for the first time in Nightmare Alley. Geek, in its sideshow sense, may have been one of them. The earliest instance to be found thus far in Billboard’s carnival section occurs in a want ad of August 31, 1946, after the novel was ready for sale: “No geek or girl shows” stated a notice that Howard Bros. shows was seeking acts and concessions. (Want ads for geeks in the carnival section of Billboard continued until at least 1960. An advertisement placed by Johnny’s United Shows in the issue of June 17, 1957, was blunt: “Want outstanding geek for geek show. must know snakes.”)

The phrase “cold reading” almost certainly appeared in print for the first time here, as did the unforgettable “spook racket.” (We become aware of the meaning of these slang terms as we encounter them. Gresham never stoops to explication through forced dialogue.)

Both phrases next show up, almost immediately and in the same sentence, in Julien J. Proskauer’s 1946 The Dead Do Not Talk, which was received by the Library of Congress almost four months after Gresham’s novel and was assigned a later control number. After that, “cold reading” is found the following year in C.L. Boarde’s slim, selfprinted, spiral-bound guide to the spiritualist’s craft, Mainly Mental, then begins to appear more widely, while “spook racket” seems to vanish to its well-deserved solitary throne beyond the veil.

The passage in which “cold reading” first appears, in the fourth chapter, “The World,” also contains one of the novel’s turning points, when the tale’s central character, Stan, reading in the long-fallen mentalist Pete’s old notebook, comes upon the words “can control anybody by finding out what he’s afraid of” and “Fear is the key to human nature.”

Stan “looked past the pages to the garish wallpaper and through it into the world. The geek was made by fear. He was afraid of sobering up and getting the horrors. But what made him a drunk? Fear. Find out what they are afraid of and sell it back to them. That’s the key.”

Here too in “The world” is Stan’s, and Gresham’s, view of the language that enthralled. As stan enters the remote piney deep South, where the fortune-teller did a better trade in John the Conqueror root than in the horoscope cards she peddled at the close of her show:

“The speech fascinated him. His ear caught the rhythm of it and he noted their idioms and worked some of them into his patter. He had found the reason behind the peculiar, drawling language of the old carny hands—it was a composite of all the sprawling regions of the country. A language which sounded Southern to Southerners, Western to Westerners. It was the talk of the soil and its drawl covered the agility of the brains that poured it out. It was a soothing, illiterate, earthy language.”

This is the language of Nightmare Alley, and many urbane critics of the time found it shocking and brutal as well. Gresham’s wicked lyricism is unique: a gutter literacy that probes the stars, at times a celestial literacy that probes the gutter.

The nightmare alley into which William Lindsay Gresham leads us is not one of moral depravity, for the nicety of morality has nothing to do with it.

Gresham’s novel is a tale of many things: the folly of faith and the cunning of those who peddle it; alcoholism and the destructive terror of delirium tremens; the playing deck of fate, which allots its deathbound destines without rhyme and without reason. what it is not is a tale of crime and punishment, sin and retribution. to see it as such is to misread it. What we consider to be crime and sin pervade this alley, but the punishment and retribution here seem more the wages of life itself.

“It was the dark alley, all over again,” Stan tells himself in Nightmare Alley. “Ever since he was a kid Stan had had the dream. he was running down a dark alley, the buildings vacant and menacing on either side. Far down at the end of it a light burned, but there was something behind him, close behind him, getting closer until he woke up trembling and never reached the light.” Stan reflects of his marks, of everyone: “They have it too—a nightmare alley.” Yes, as stan—that is to say, Gresham—observes elsewhere, fear is the key to human nature.

And stan and gresham were indeed one. There is a bizarre letter, frayed and torn, preserved in the collection of the Wade Center of Wheaton College, written by Gresham in 1959, when the end was near. In it he wrote: “Stan is the author.”

Upon its publication, in September 1946, Nightmare Alley was an acclaimed and successful novel, and a damned and banned one. For thirty years after the first edition of 1946, every edition remained corrupt and censored. To use but one example, instead of “society dames with the clap, bankers that take it up the ass,” readers encountered “society dames with a dose, bankers that have fishy eyes.”

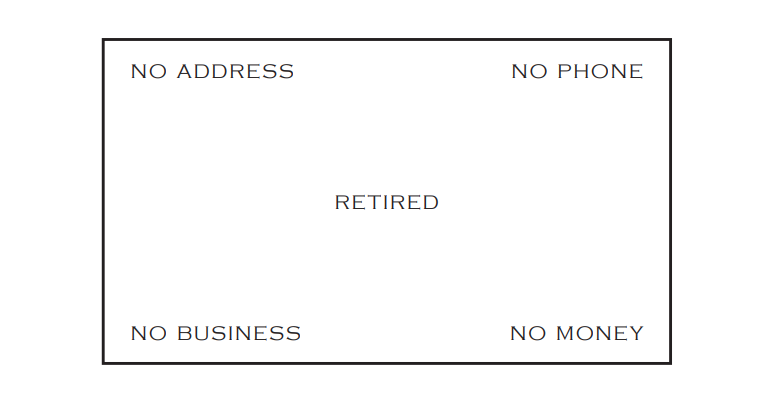

Within little more than a decade, it was all but forgotten. sixteen autumns later, in September 1962, Gresham’s body was found, selfkilled, in a hotel room off Times Square. He has just turned fifty-three a few weeks before. In his possession were business cards that read:

And so the alley, and the running, and the light beyond reach came to an end—for the man who wrote of that alley, if not for us who read of it.

___________________________________