“If you identify more with the city of Los Angeles than the movie industry, it’s hard not to resent the idea of Hollywood, the idea of the movies standing apart from, and above, the city.”

–Thom Anderson, Los Angeles Plays Itself

I moved to Downtown Los Angeles in late 2007. I’d lived in Southern California for a number of years, but most of my understanding of the City of Angels came almost exclusively from movies and television. My biggest problem in consuming an exclusively cultural diet was that I thought of Los Angeles as monolithic, that it existed as a single metropolis. It took me moving here, and riding the bus, to learn that it isn’t, and it doesn’t.

Los Angeles is a city in a large, sprawling, dense county of the same name. Often, when people say Los Angeles, they mean all of Los Angeles County. It’s shorthand. What they most often mean is everything: the city, sure, but Santa Monica, Beverly Hills, and Pasadena, too. But these are not neighborhoods; these are cities with independent tax bases, policing, fire departments, and school districts.

As it turns out, some areas are also left out of this wide-ranging definition. It isn’t completely inclusive. You see, when people say Los Angeles, they don’t tend to mean South Central. They rarely mean Compton, South Gate, or Lynwood. These, too, are separate cities, islands unto themselves, and veritable no-go areas for many county residents.

In fact, I was told not to visit South Central Los Angeles before researching my novel, All Involved. The message was implicitly clear: people who look like you don’t/can’t/shouldn’t go there. What’s worse, there seems to be an underlying mentality that nothing of value comes from, or exists, in these places, which is a dangerous notion, indeed, as it directly reflects on the residents of these areas. To visit such places is to go at one’s peril, for no good reason; this seemed, and seems—even now—to be the prevailing sentiment.

I went anyway. I spoke to former gang members, nurses, firefighters, and other citizens who lived through the 1992 LA riots. What I heard changed my view of Los Angeles, as well as my own understanding of my writing and work. I’ve kept in touch, too. A few years ago, one of these folks called me at five o’clock on a Sunday morning with a question: did I want to see a safe get cracked?

Yes. Yes, I did.

That day, I spent hours in a garage with two gentlemen who punch safes for a living. They’re freelance, hiring out to the DEA, FBI, and others. I was allowed to ask questions. Were they ever left alone? All the time. Did anyone come back? All the time. A gun had been pointed at one of them last week. How do you talk someone out of killing you? After exchanging a glance, the men gave some insight into their psychology of survival. Suffice to say, it was one of the most fascinating conversations I’ve ever heard.

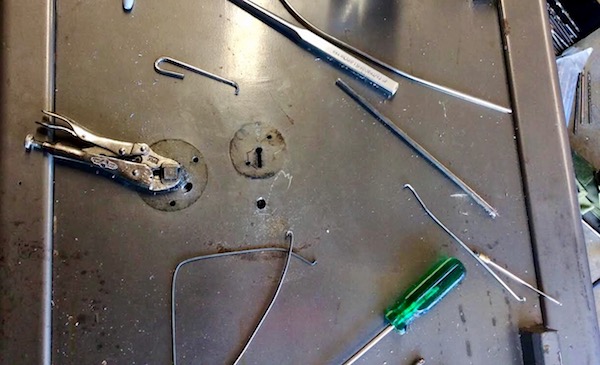

This is the only photo I was allowed to take that day.

Watching a safe get cracked is different to how it is fictionalized on-screen. In person, it involved drilling, not stethoscopes, which makes me think of what else Hollywood so often gets wrong about Los Angeles: the landscape. On film, geography is often cut, spliced, and re-imagined. A scene ostensibly taking place in LA County might actually be cut together with shots done on sound stages, or might actually be another city entirely.

This dislocation of space and place is what I try to counter with my novels. I aim for specificity and detail, making use of actual streets, buildings, and routes in my work, grounding arcs and plots in the physical world.

There’s a saying in Los Angeles: “Don’t go south of the ten.” It refers to the 10 Freeway, which bisects the county, ending in West LA, effectively separating north and south. Traditionally, North (Pasadena, The Valley) and West (Beverly Hills, Santa Monica) are considered desirable; South and East are not.

I live well south of the 10, and it’s where my stories almost exclusively take place, because I rarely see these places on-screen, and if they are, they’re scarcely respected. South Central, in Hollywood’s imagination, has always been a place for villains, and few heroes.

With my work, I seek to counter that notion, but not simply to present heroes instead, but to show why and how people do what they do in a criminal context. I think it necessary to explore the humanity of criminality (in its varied forms) as deeply as I can. I seek the details that only those who engage in it would know (that I myself would never know if not for some thoughtful words and advice), but maybe even more important, I seek how it feels to do such things and crystalize that in my fiction. I want to capture the emotions and thinking behind dangerous decision-making.

I know how lucky I am. I know few people get to discuss underground economies with folks who have actively participated in them. I’m not certain how many writers who write about murder, or murderers, have had the chance to meet with people who have actually committed such a crime. I have. I know what it feels like to sit down with them. To ask questions. And weigh body language. Which is why my goal, when it comes time to sit down and write, is to give my readers a solid sense of what that feels like to be there; I want to immerse you in that environment, to illustrate how it feels to sit across from someone capable of anything, and that means representing such places as faithfully as I can.

It’s not simply for verisimilitude. I’m also trying to push this sense of access, the feeling of what it’s like to be there, through to my fiction so that readers can feel for themselves—at a safe physical distance if not an emotional one—the power and atmosphere of this world.

I don’t know that it’s possible to capture that kind of environment without a setting strongly tied to the world as I know it, which is why I do my utmost to extend this realism to the geography of place as well. I choose real places, not simply because they inspire me, but because they anchor the story to place and to time, and also because certain places make certain actions not just possible, but probable, or even inevitable.

In Safe, the narrator known as Ghost starts his journey on 1st Street in Rancho San Pedro, just up from the old ferry terminal and the Port of Los Angeles:

When Ghost has breakfast in Rancho Dominguez, in the East Compton neighborhood where Venus and Serena Williams first learned to play tennis, he goes to Tamalería La Doña—a place where men shuck corn and women shape tamales:

When Ghost visits Compton’s Crystal Casino Hotel for an important drop, he goes to room 626, which overlooks the 91 Freeway:

When Ghost needs a place to meet that has two exits (one to the 405 Freeway), he chooses the South Bay Galleria’s parking structure:

When Ghost seeks an end-point for his journey, he returns to Korean Bell Park in San Pedro—the very same place he visited years ago with the love of his life, Rose:

My research process is simple. I travel my county. I drive the streets. I talk to real people who have done the things I explore in my novels. For Angelenos who know the area well, it’s a nod of respect. For those who don’t, it corresponds to an actual road map. If a character is ever giving directions in one of my books: it is how you actually get there, and it contains the same obstacles you might reasonably expect to find on the way—or could find, at the time the piece is set, whether in 1992, or 2008.

I do this because I want my work not to stand above the city, but to stand in the city, at eye-level—where it’s fused to the same streets I drive when I’m in Lynwood, San Pedro, or Hawthorne—because I believe anchoring my stories in real places, on real streets, not only enhances the believability of the story and honors the folks who aid me in my research and background, but better immerses unfamiliar readers in a place worth knowing.