When #MeToo hit, I watched the stream of posts from celebs and friends and former colleagues and student buddies and women I’d met once at a literary festival and the girls I’d grown up with and the other mums from school; I’d always known it wasn’t just me who’d been harassed and hurt, but now I thought, it’s everyone. I added my own little #MeToo to the list. Writing out those few words made my hands shake, my heart hammer; I messed up a day’s work with anxiety. These things aren’t easy to share. Even the headline fact, let alone the details.

It wasn’t everyone. Of course it wasn’t everyone. I do know women who haven’t been assaulted, harassed, raped or abused. A shrug, a smile: not me, thankfully. That’s a comfort; it gives me hope. But at that time, there were others conspicuous by their #MeToo absence; the ones I know who’ve had it worst. Friends who’d told me about the brutal, violent acts inflicted on them, about traumas that made my own seem to turn to paper scraps and blow away. They weren’t going to be giving all that light and air again, overturning whatever equilibrium they’d achieved, just so that some dude on Facebook could point out that not all men are like that, actually.

This is the weirdest thing about violence against women: it’s normal. Violence, and the threat of violence, is not something we encounter only in fiction, in books or film or on TV; for so many of us it’s real; it has already happened.This is the weirdest thing about violence against women: it’s normal. Violence, and the threat of violence, is not something we encounter only in fiction, in books or film or on TV; for so many of us it’s real; it has already happened. We’re just trying to get on with things, but we’re living in bodies that have been primed for fear. I think this is something most guys just don’t realize this when they’re chatting up or catcalling a woman. That rhetorical question yelled from building sites could really do with a frank and detailed answer: ‘smile, love; what’s the worst that could happen?’ Well since you ask…

I’m not suggesting that because it’s real for us, we should therefore be somehow protected from depictions of violence in books or on our screens. On the contrary; we need to talk, we need to write, we need to make some kind of sense of our experiences. It helps to see ourselves represented. It helps to see our experiences reflected in the fictions we encounter; but it’s profoundly troubling when the reflection is so distorted that it bears no resemblance to lived experience.

One of the biggest, weirdest distortions in the depiction of violence against women is the way that violence is eroticized. It’s a crowded field, including some books that take themselves very seriously indeed, but for me one of the most egregious examples of this is in the BBC TV drama The Fall. A veneer of respectability, a ‘quality drama’ sheen is conveyed by its BBC provenance, but underneath there’s something deeply unpleasant about this show. What troubles me is not that it’s about sexual violence, but the way that it just loves looking at it. To paraphrase Laura Mulvey in her seminal essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, there are three looks going on here: that of the camera as it records, that of the audience as it watches, and that of the characters as they engage with each other. And in The Fall, the camera is complicit with the rapist-murderer; its gaze lingers on women’s terror, on women’s bodies as they are subjected to violence, on a victim’s lingerie and sex toys (really, yes; they went there). With elaborately-planned heist-like attacks and the casting of Jamie Dornan in the role, The Fall clearly finds this rapist-murderer charismatic, sexy, cool. And it assumes we, the viewers, are his hangers-on too: it makes us look where he looks, linger where he lingers; unless, that is, we choose to look away.

***

It helps to see ourselves represented, but that’s only if it is as actual persons, rather than narrative devices. Too often the female presence is a puzzle within a male narrative, a problem to be solved. From the princess in the turret, to the femme fatale sashaying into some Dick’s office, a woman—or more specifically, a woman’s body—is an initiating incident. Especially when she turns up dead. Either found naked, or stripped for the autopsy, her body is pored over, made to give up secrets, while she herself doesn’t get to speak a word.

Too often the female presence is a puzzle within a male narrative, a problem to be solved.I do feel for those young story-of-the-week women actors, lying motionless as the male regulars crowd round and the camera catches a chilly nipple and someone lifts a limp limb and studies torn fingernails; but it’s not just a trope of TV: classy Booker-shortlisted novels such as Eoin McNamee’s The Blue Tango do much the same thing. Throughout this true-crime story, female beauty, sexuality and death form a kind of portmanteau of meaning; to be beautiful is to be promiscuous is to be abused is to be dead. Even a minor character’s hair is described as ‘sex-crime blonde;’ as though that’s a shade L’Oreal are doing; as though your hair color is the cause of your abuse. As a woman, a reader, as someone who’s experienced violence, this feels alien and uncomfortable and, well, frankly, lazy: can we just please agree that her murderer is never the most important thing about a woman?

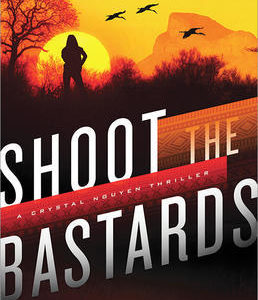

I do understand that what I’ve described above are simply ways of generating stories, and that as writers we are always looking for ways to generate stories. But it’s always a choice. The same subjects can be explored and stories can be told so differently; it just takes a slight shift of perspective, a different decision. In Julia Heaberlin’s Black-Eyed Susans, the protagonist Tessa, the lone survivor of a serial killer, digs her nails right into the Naked Dead Girl story and claims it as her own. Haunted and damaged by her experiences, she’s also the active narrative force in this story; the killer is a washed-out and faded presence in comparison with her. Hallie Rubenhold’s The Five, an account of the lives of the victims of Jack the Ripper, is an extraordinary piece of social history, and a necessary counter to a cultural obsession with the murderer. Her refusal to engage with the mythology of their killer has itself provoked misogynistic sputterings from ‘ripperologists’ on Twitter (check out #readthebookTrevor).

Jane Campion’s Top of the Lake, as opposed to The Fall, really does get Strong Female Lead right: a woman who is battling with her own profound trauma, as she seeks to unpick the corruption and complicity at the heart of her community, and save other young women from similar abuse. And since I began with pasting a BBC drama, I’ll end with celebrating one: Five Daughters, a dramatized account of the 2006 Ipswich serial murders in Suffolk, England. Written by Stephen Butchard, the series focuses not on the police hunt for the killer, but on the troubled lives his victims led; the trauma, addiction and destitution that made them, like the Ripper’s victims, vulnerable to the actions of just a really shitty man. The stories told here are heart-breaking, powerful, and necessary: a counter to the convention that the killer is the natural focus of the narrative; that he is charismatic, cool. Truth is, if you were casting to type, you wouldn’t be casting Jamie Dornan. As Jess Walker put it when speaking about the origins of his book Over Tumbled Graves, real serial killers aren’t fascinating; they are ‘the kind of broken, weak-minded loser who preys on women on the fringe of society; [they are] in some important and horrifying way, smaller than life.’

I was trying to pick my way through some of this with The Body Lies. I wanted to tell a story that engaged with these tropes, and the reality of lived experience, and the struggle to reconcile the two, particularly when you’re trying to get around in the world, as so many of us are, in a female body already freighted with hurt and fear.