“It is easy to take liberty for granted when you have never had it taken from you.”

Lou’s last meal at Jackson was on the night of the first debate between Cheney and the Jewish guy. He’d barely scarfed down the food, shoved through the port, when the guard came back and yanked it away. He was being fed in his cell to avoid last minute altercations, standard Jackson protocol for cons who were short-time.

The guards herded the most docile prisoners into a common room where the monitors were tuned to the debate.

“Can’t we watch the poker channel instead?” someone joked, getting his head clipped in response.

“Porn, porn!”

It didn’t have to be a good joke to evoke laughter, and the noise level rose.

“Shut the fuck up,” a kid said. “I’m trying to hear the old dudes.” This brought another round of guffaws.

“Not that any of you can vote, but you might learn somethin’,” a guard said. “Be a test when it’s over—for the ones of youse who can write.” It was the guards chortling now.

Lou returned to his cell later, impressed with the two candidates. All the—whadya call them—commentators—agreed. Grandfatherly types, they called ’em. Kind of man he should become if he didn’t want to end things with a backdoor parole—the way he’d always expected to leave here. He was gonna change his ways, make his girl proud. Take his grandson, Jason, outside and toss some balls. He looked at his tank, remembering there’d be none of that. Did kids still play Uno?

He’d put a lot of mileage between himself and the past. Shove a stick up his ass and be upright. Be a Cheney and Joe What’s His Name kind of guy.

“Except for the occasional heart attack, I’ve never been better.”

The parole came through once he went on oxygen twenty-four seven—a special handling case, pain in the butt. Prison croaker put in the word after he got the cords to his tank tangled in a geezer’s wheelchair for the umpteenth time. Cons spending most of their lives in prisons usually ran out of housing options. Relatives died, drifted, got displaced. But he had his daughter, Marcie.

Marcie set him up in the back room—the one used for sewing projects, storing junk, laundry. Air smelled of spray starch, fabric, moth balls. Her iron board and sewing machine loomed over him. When he woke and saw the shadow of the plank on the wall, he thought someone was coming to shive him. He’d learned to sleep on his back watching the door a long time ago.

Jason was sixteen now, too old for Uno. Looked at his grandfather like he carried a filthy disease. His son-in-law, Stuart, watched the machine sucking air out of the room like his own lungs provided it, like the tank was debiting money directly from his bank account. Winced every time Lou’s cords tripped someone, when he had to use his inhaler, when he didn’t stay out of the way, when he did his old-man business in the toilet, when he ate too much.

“I had other priorities in the sixties than military service.”

Lou’s life had been ruined in Nam—that’s where he’d learned to smoke, drink, take dope, kill, steal. Men like Cheney sent him there. Grandfathers, lethal ones, sitting on his draft board like a panel of executioners.

Time passed. A lot of time. He was watching TV most of the day, following the news on CNN.

“Not even a beer when I get out of here?” he’d asked the croaker.

“You gotta stay on your toes,” the guy had said, patting his shoulder. For what, he wanted to ask?

Terrorists, Halliburton, friends getting shot in the face, boys spending years in places he couldn’t find on a map. WMD—that was the term Cheney liked to throw around. Old Dick didn’t look so grandfatherly anymore—spent most of his time in some unnamed bunker watching George’s back. Using that phrase over and over. WMD.

Lou’s life had been ruined in Nam—that’s where he’d learned to smoke, drink, take dope, kill, steal. Men like Cheney sent him there. Grandfathers, lethal ones, sitting on his draft board like a panel of executioners.

Soon Jason might be in a war too.

“Go f*** yourself.”

One day the call came. Marcie’d bought him his own cell phone, probably so he didn’t have to vacate his roost. Bought a second TV, had it installed on his wall. His situation was like the prison break room, but smaller and more humid. She’d begun bringing his dinner in on a tray. He’d love to live on his own—even Jackson looked kinda good. He and Cheney had that much in common—holed up in a goddamned bunker.

He’d no idea how Willie Sandy got his number.

“So they sprung you?” Willie said. Eleven years since they’d pulled the job—the one that got Lou thrown in the slammer. A jewelry store where Sandy’s niece once worked. She’d told them about a slim skylight over the backroom, and a few weeks later they were removing the glass, sliding in around two a.m.

“No one knows about it,” she’d insisted, thinking of her part of the take. “Hidden by a chimney and crappy tarp.”

Inside, they smashed through the glass cases with a hammer. Then it happened. Lou cut his finger. Left a fuckin’ bloody print behind. Cops picked him up within hours. Recovered the jewels in the trunk of his car. He swore he’d done the job alone. Since he’d mostly worked alone in the past, they bought it.

“Sharky still has the diamonds from that other job—the month before,” Sandy told Lou on the cell. “Been sitting on those rocks all these years. Just fenced the gold.”

“That don’t seem right,” Lou said. But why would Sandy lie?

Lou’d never been convinced the two men weren’t in cahoots back then—that they weren’t living it up while he festered in Jackson. Maybe they’d even engineered the bloody print on the counter after the alarm went off. These were the paranoid fantasies that years beyond bars put in your head. Fixating on revenge can make you nuts.

“Are you kiddin’ me?” he said now. “You’ve had the last five years to run him down. Why you calling me after all this time?”

“Diabetes,” Willie Sandy said. “Lost my feet a few years back. Some of that money sure would help me out.”

And me too, Lou thought, but didn’t say it. “How the hell can I track him down?” he said, looking at his tank. He couldn’t bring himself to tell Willie about it. Seemed too pathetic—even to a man with no feet.

“I know right where he is.”

“My belief is we will, in fact, be regarded as liberators.”

Sharky Black got rinsed at the Dearborn Dialysis Center. “Takes till three. Follow him home or wait in his car—nineties Cutlass. Blue.” Sandy told him.

“How’s it you know where he’s doing dialysis and the make of his car, but not where he lives?”

“Had that car forever. And I know a guy who knows a guy.”

Lou sighed. “I’ll have to follow him home, see where he lives, and get him next time. I’m not movin’ too fast nowadays. Look, there’s no guarantee there’s anything left. Eleven years is a long time.”

“Local fences claim none of the big stuff ever turned up.” Sandy knew his fences—that’d always been his thing.

Lou borrowed Marcie’s car for an alleged doctor’s appointment and found the facility.

It was a good ten minutes before Sharky exited, got the car started, and pulled out of the lot. Lou followed him home Wednesday and was waiting for him on Friday.

“Bet you’re weren’t expecting me,” Lou said, sitting in what was clearly Sharky’s favorite chair, his mini oxygen tank in his lap, a gun in his hand.

“Geez, Lou, you scared me. Isn’t that kind of dangerous?” he said, nodding at the gun. “With your tank and all.”

Lou didn’t answer.

“When you get out?” Sharky sank onto the sofa, tossing his car keys on the table.

“Few years back. Guess you know why I’m here.”

Sharky nodded. “Too late, Lou. Sold the stuff.”

“Sandy says he checked with every fence in the state. None of it ever turned up.”

“Didn’t fence it exactly.”

“What then?”

“Heard about the emphysema, Lou,” Sharky said, looking at the tank again. “Not much they can do for it, is there?”

Lou shook his head.

“And no way Sandy can get himself new feet. Good chair’s about it.”

“He can live better with some dough. So can I.”

“I thought about that. But when it came down to it, the money can help me best. Can’t buy you new lungs or Sandy new feet. So I bought myself a new kidney. Just got the call—some kid who died in a car crash. Surgery’s tomorrow. You can kill me, Lou, but you still won’t get the dough and you’ll probably go back to Jackson. Do you see my point? That money moved me up to the top of the list, bought me a few more years. Maybe more.”

“Or maybe less.” Lou pulled the trigger and watched Sharky slip onto the floor. If he’d known where kidneys were, he’d have plugged the bastard there.

He’d always figured on a backdoor parole, and fuck if it wasn’t pretty much the same as the backroom one he had now. He turned the air back on and walked out.

“We must be prepared to face our responsibilities and be willing to use force if necessary.”

__________________________________

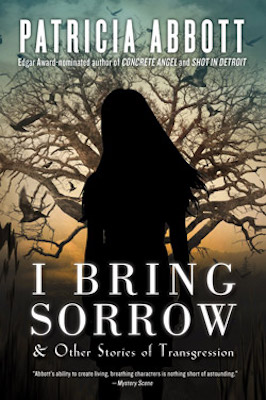

From I Bring Sorrow: And Other Stories of Transgression. Used with the permission of the publisher, Polis Books. Copyright © 2018 by Patricia Abbott.