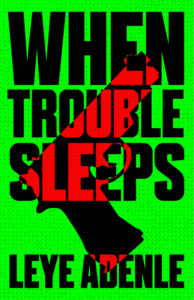

I first came across Leye Adenle’s debut, Easy Motion Tourist, back at the bookstore I worked at before moving up to New York, and, seduced by the stunning cover design, took it home and immediately sped through it. The fast-paced action sequences and badass heroines held me spell-bound, and the setting of Lagos fascinated to no end. When Leye Adenle’s second in the series came across my desk, I was happy to discover that When Trouble Sleeps is just a complex, action-packed, and good-hearted as the first, with plenty of wicked humor. Adenle is part of a new group of Lagosian crime writers putting Nigerian Noir on the map. I caught up with Leye Adenle via email to ask about the series, the characters, and of course, the city of Lagos.

Molly Odintz: This is the second work to feature the incredibly badass character of Amaka, who uses her many talents, as well as her position as part of the nation’s elite, to advocate for sex workers and extract her own revenge on those who abuse the women of Lagos. What was your inspiration for the character?

Leye Adenle: My mother. It took me three years, and an audience member in France asking where mum is in the book to realize it. The idea for the very first book in the series came to me in the middle of a conversation I was having with my mum and two of my brothers. More of a debate, actually. The four of us, when we get together, discuss and debate everything from polytheism and ancient religions of Asia minor, to irrigation solutions for the arid regions of Northern Nigeria (she had a brilliant idea decades ago and sent a paper to the government), to Nigerian movies and music stars. Somehow, that evening, we had segued to talking about murder victims dumped on an expressway in Nigeria notorious for dumped bodies. The victims were usually young women, always naked, and often missing body parts, a combination of clues that led people to two conclusions: they were sex workers, and they were victims of black magic rituals. It was while trying to solve this problem, which is what we do when we get together, that I thought of another potential explanation for the murders, got the idea to put it into a book, and Amaka was born.

Until I realized that Amaka is my mum, I’d answer the question, what inspired Amaka, by saying that she’s a composite character of the women in my life, and then I’d list my mum, my sisters, my ex partners, my friends, my colleagues, but once that question was posed to me: ‘Where is your mother in the story?’ it became clear. She is Amaka. They both spend their lives fighting for justice for women. They both get things done their own way. They both come up with ingenious solutions to problems. They are both incapable of ignoring injustice.

Once that question was posed to me: ‘Where is your mother in the story?’ it became clear. She is Amaka. They both spend their lives fighting for justice for women. They both get things done their own way. They both come up with ingenious solutions to problems. They are both incapable of ignoring injustice.Nigerian literature has a long history of embracing genre fiction—I’m thinking of all the action thrillers released by Macmillan in the 70s, specifically. What paved the way for a revival of genre fiction in Lagos, or has genre fiction always been popular?

I grew up reading everything from Famous Five, to The Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, the Macmillan Pacesetters novels, Mills & Boons (yes, I know), James Hadley Chase novels, Fredrick Forsyth, and the list goes on. And I didn’t have to go far to find these books, they were everywhere, we exchanged them at school. The appetite for genre fiction has never gone away; the supply of books by African authors is what has suffered. I dare not put forward a theory on why this was (still is?) the case.

Your action sequences are impeccably choreographed. What’s your craft advice for plotting, and running a tight ship? Are you an outliner or do you prefer to just start writing?

I just start writing. And I continue writing until the characters come alive and start doing what they want and how they want and when they want to. Then I become nothing more than their audience, witnessing their actions and being entertained by them.

I just start writing. And I continue writing until the characters come alive and start doing what they want and how they want and when they want to. Then I become nothing more than their audience, witnessing their actions and being entertained by them.

Easy Motion Tourist was a perfect example of the “ordinary man swept up in an extraordinary story” subgenera of crime fiction, and reminded me a bit of The Man Who Knew Too Much. When Trouble Sleeps, in contrast, felt like a more epic, cinematic take on the genre. What are some of your crime fiction influences in crafting the series?

Every book I’ve read, every movie I’ve seen, and every song I’ve listened to, all have and still influence everything I write. And comics. I think I write primarily in ‘comic mode.’ I see the scenes and I try to describe them without the benefit of dramatic graphics.

Your series treats sex worker characters with a rare respect. I admired your sensitive portrayal of sex workers, and especially, your willingness to allow them to be agents in their own fates, rather than buffeted by forces around them. Can you talk a bit more about the role sex workers play in your series, and in Lagosian life?

Sex workers in my opinion, suffer the worst form of violence against women, which is my primary concern. In the series, they serve as symbol of the larger problem: the violence of patriarchy.

Lagos is as much a character as any person in the story, and it seems there are many faces to the city of Lagos—can you tell us a bit about how the setting shaped the novel?

I love Lagos. I wanted readers to see the Lagos I love. I realized that to make Lagos come alive, I had to show not tell. I gave Lagos a voice through the foreigner narrator, Guy. Through his eyes and his experiences, we see Lagos, we hear Lagos, we get to know Lagos and we feel what she feels as we follow her on her arc.

Your work is part of a whole wave of Nigerian crime fiction, with Lagos as its epicenter (please correct me if I am wrong). What can crime fiction say about modern Lagos that other genres cannot? What makes Nigeria such a happening place for crime fiction?

Crime fiction is that one genre that serves as an indictment of society. You can tell a lot about the wellbeing of a society through the crimes committed. Crime begets crime. Corruption, police brutality, petty theft, murder, racketeering, fraud, all are linked. To solve certain types of crimes, they often say, follow the money—I say, follow the failure in society. Crime fiction says to society, ‘See. Look at yourself. See what you have become.’

Why Lagos? Lagos is the kind of character any writer would want in their story: larger than life, flawed, conflicted, dramatic, driven, consistent and yet unpredictable. A character with agency.

It’s a brutal, capitalist, man eats dog, dog eats man, everything eats everything life. Humor is the favorite drug to numb the soul.The novel ended in a way that left me begging for the next one—can you tell us a bit about the next book in the series?

I started what I thought was book three but Amaka is yet to make an appearance save for a phone call in which she declares, ‘I am back.’ It’s looking more like a Lagos story than another Amaka thriller, and I’m afraid that forcing Amaka into the storyline might come across as a contrivance. For deeply personal reasons, writing Amaka at the moment has become very painful for me. Maybe subconsciously avoiding this pain is what’s affecting me and keeping her out of the current book I’m working on.

When Trouble Sleeps is brutal, but preserves a cynical humor and a certain faith in humanity throughout. How did you balance the novel’s high body count with its witty banter, sendoffs of hypocrisy, and touches of humanity?

Lagos is exactly like that. A harmony of contrasts and contradictions. And Lagos is brutal—try telling the six-year-old who lives under the bridge otherwise. It’s a brutal, capitalist, man eats dog, dog eats man, everything eats everything life. Humor is the favorite drug to numb the soul.

You live in London, and grew up in Nigeria—could you have written the same novel if you were still living in Lagos, or did geographic distance aid in the writing process?

I think there’s something in looking in from outside. I was living the life of my characters and in their world when I lived in Lagos. Stepping out, I have the benefit of what I call the God’s eye view: I can see everything from above, unaffected by my own role in the evolving drama.