Scanning the face-out selection of crime and thriller novels in a modern American bookshop, one can’t help but recognize homogeneity in cover designs. There are certainly exceptions. However, parsimonious publishing budgets, the rise of stock photography enterprises, marketing-driven fears of offending readers, and what now seems to be an annually escalating number of new books requiring wrapper embellishment have conspired to leave us with too many novel façades that lack much novelty at all.

This wasn’t always the case. During the mid-20th century, when the spread of low-cost paperbacks revolutionized the book-publishing industry, newsstands and drugstore spinner racks were packed with tales of criminality boasting commissioned cover paintings intended to titillate, shock, and thereby separate customers (primarily men at the time) from portions of their paychecks. That sensationalistic artwork routinely traded in lust and violence, sadism and imminent disaster; and though sententious critics howled, readers couldn’t grab up such pocket editions fast enough.

Myriad people deserve credit for those frequently gorgeous cover paintings, which were standard elements of paperbacks until at least the late 1960s, when they began to be replaced by more easily acquired and ostensibly more “modern” photographs. But the dozen artists cited below were responsible for some of the most captivating and memorable examples of the breed.

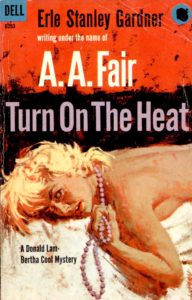

- Turn on the Heat, 1958. Illus. Robert Abbett

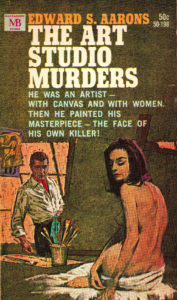

- The Art Studio Murders, 1964, Illus. Robert Abbett

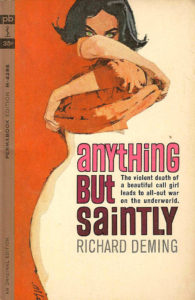

- Anything But Saintly, 1963. Illus. Robert Abbett

Robert K. Abbett (1926–2015)

Born in Hammond, Indiana, the son of a paint salesman, Abbett early on imagined spending his professional life behind a camera. Yet after serving with the U.S. Navy Air Corps in World War II, he earned a Fine Arts degree from the University of Missouri and undertook jobs as a commercial artist in Chicago before moving to Connecticut. Proximity to New York City helped him win assignments to paint covers for Permabooks, Ballantine, Pyramid, and other publishing houses. His efforts graced works by crime novelists ranging from Robert Kyle and Richard Deming to A.A. Fair (aka Erle Stanley Gardner), John Creasey, and William Campbell Gault. As he grew older, Abbett specialized in fine-art paintings of dogs and less-cosseted wildlife.

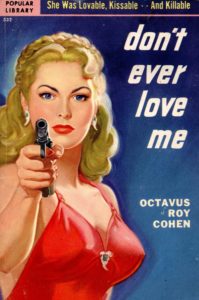

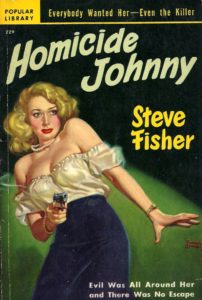

- Don’t Ever Love Me – illus Rudolph Belarski

- Homicide Johnny – illus Rudolph Belarski.2

- The Death Wish – illus Rudolph Belarski

Rudolph Belarski (1900-1983)

A child of Central European immigrants, Belarski grew up in an eastern Pennsylvania coal-mining town and quit school at age 12 to toil in those mines. But he also enrolled in mail-order art courses, and in 1922 went to study art at New York’s Pratt Institute for four years. His first post-graduate commissions were for Dell Publishing, devising covers and interior illustrations for adventure pulp magazines, and for Thrilling Publications, which tasked him with painting covers for Popular Detective, Black Book Detective, Thrilling Detective, and similar journals. Too old for military duty, Belarski spent the 1940s war years with the USO, drawing portraits of hospitalized servicemen. That helped further sharpen his skills, and by 1951 he’d become a leading artist for New York-based Popular Library, delivering lively, often riveting artwork for novels by Elisabeth Sanxay Holding, Rufus King, Steve Fisher, Patricia Wentworth, and their like. Those fronts typically showed women being menaced by men, but on occasion it was the women who were most dangerous.

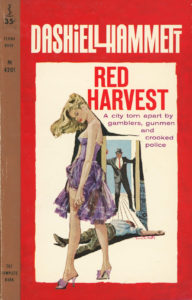

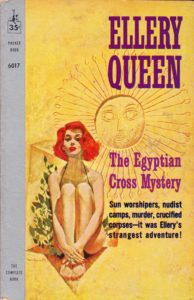

- Red Harvest, 1961 – illus Harry Bennett.3

- The Egyptian Cross Mystery, 1965 – illus Harry Bennett.2

- The Man with the Getaway Face, 1963 – illus Harry Bennett.3

Harry Bennett (1919–2012)

During a more than three decades-long freelance career, Bennett developed the anterior imagery for everything from detective novels and Gothic romances to Hitchcockian thrillers and yarns about amorous young nurses. Trained at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and the American Academy of Art in that same city, he spent most of his long life (before dying at age 93) in Ridgefield, Connecticut. It was there, according to an obituary, that Bennett “would use his family [including his five children] and neighbors as models for over 1,000 book covers and illustrations …” His stylistically diverse illustrations adorned works by Agatha Christie, Ellery Queen, and Dolores Hitchens, but it’s the uniform series of paintings he did for such writers as Chester Himes, Frank Kane, Richard Stark (aka Donald E. Westlake), and Dashiell Hammett that draw the most attention from vintage book buyers.

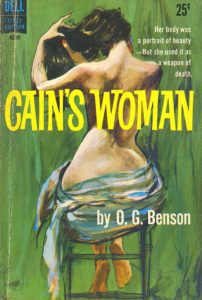

- Cain’s Woman, Dell 1960 – illus Ernest ‘Darcy’ Chiriacka

- The Best from Manhunt, Permabooks, 1st printing March 1958 – illus Darcy

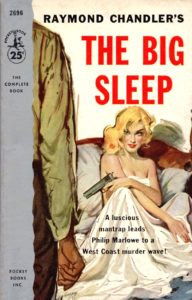

- The Big Sleep – illus Darcy

Ernest Chiriacka (1913–2010)

The son of Greek immigrants, Chiriacka was born in New York City as Anastassios Kyriakakos, but he went on to sign many of his cover paintings as “Darcy.” He started out as a teenager crafting business signs in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, but by the late 1930s had moved up to illustrating stories for pulp magazines on the order of Argosy and Dime Detective. Because he was ineligible for military service (due to a “pre-diabetic health condition”), Chiriacka was able to enhance his style and gather more customers for his work during the Second World War. By the ’50s, he was submitting illustrations to slick magazines, and gained a large following with his pin-up calendars for Esquire. Not until the 1960s did Chiriacka begin his paperback efforts in earnest, but he rapidly established himself with canvases rich in color, bold in line, and sexually suggestive.

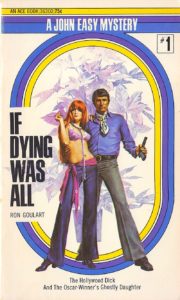

- If Dying Was All, 1971 – illus Elaine Duillo.2

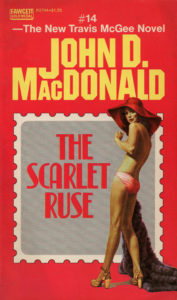

- The Scarlet Ruse – illus Elaine Duillo

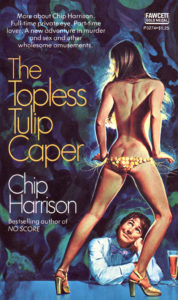

- The Topless Tulip Caper – illus Elaine Duillo

Elaine Duillo (1928– )

Duillo was a rare woman infiltrating the boys’ club of mid-20th century paperback illustrators. Rare enough, in fact, that she felt compelled to sign her early submissions with male monikers. A child of Brooklyn, she attended New York City’s High School of Music & Art, where she met her future husband, John Duillo (who also grew up to be a prominent artist), and then the Pratt Institute. Around 1960, she began doing magazine and book-cover work. Duillo may be most familiar for the realistic and luminescent portraits she painted for romance novels (she’s said to have created “hundreds of Gothics,” and was instrumental in introducing Fabio Lanzoni as a cover model for the genre). Yet her talents are also seen on Edward S. Aarons thrillers, Ron Goulart’s John Easy private-eye stories, and the erotic mysteries attributed to “Chip Harrison” (aka Lawrence Block). Elaine Duillo retired around 2003.

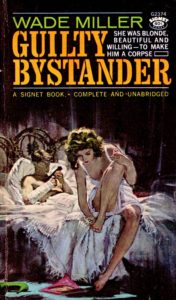

- Guilty Bystander, 1963 – illus Mitchell Hooks.3

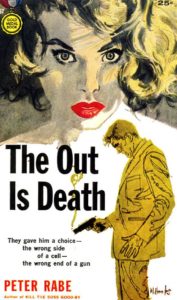

- The Out Is Death – illus Mitchell Hooks

- The Way Some People Die, June 1977 – cover art by Mitchell Hooks.2

Mitchell Hooks (1923–2013)

Hooks said that as an aspiring artist he was influenced by newspaper cartoon strips, especially Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon: “I’ve always had an affinity for anatomical drawing, and, in retrospect, I can attribute my abilities to the long hours spent studying Raymond’s beautiful drawings.” Reared in Detroit, Michigan, Hooks later took employment with General Motors, converting two-dimensional blueprints into three-dimensional drawings, before hieing off to Europe with the U.S. Army during World War II. He subsequently settled in New York City, where he found opportunities in commercial art before scoring magazine-illustrating gigs and embarking on a career painting fronts for mass-market paperbacks. Hooks developed covers for a plethora of prominent crime and espionage fictionists, among them John D. MacDonald, Margaret Millar, Eric Ambler, Wade Miller, and Peter Rabe. He’s also fondly remembered for the covers he conceived for Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer series in the 1970s.

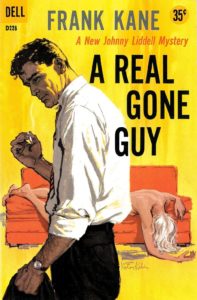

- A Real Gone Guy, 1958 – illus Victor Kalin

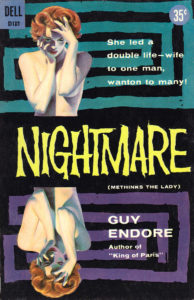

- Nightmare – illus Victor Kalin

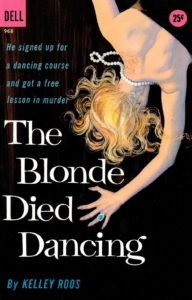

- The Blonde Died Dancing – illus Victor Kalin.4

Victor Kalin (1919–1991)

Belleville, Kansas, native Kalin became a mainstay supplier of art to Berkley, Dell, and other softcover publishers during the 1950s and ’60s. His work—incorporating visual clues from the book’s story, or conveying its sinister or mysterious tenor—might have been simple in content, but it was sharply and dramatically presented. Kalin’s illustrations for a late-’50s line of Frank Kane’s Johnny Liddell private-eye tales make those editions eminently collectible, and the still-lifes he produced for reprints of John Creasey’s mysteries lend them particular distinction. Mary Roberts Rinehart, Thomas B. Dewey, John Dickson Carr, and Harold Q. Masur also benefited from Kalin’s creative acumen. As demand for original paperback art declined, Kalin—a lifelong music lover—brought his artistic vision to record-album covers. It’s said he painted more than 100 such cardboard casings.

- The Damned Lovely, Signet 1955 – illus Robert Maguire.3

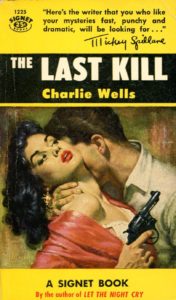

- The Last Kill, 1955 – illus Robert Maguire

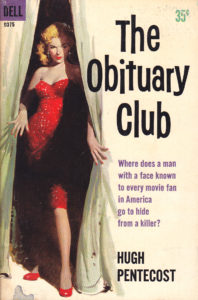

- The Obituary Club – illus Robert Maguire

Robert Maguire (1921–2005)

Growing up in New Jersey, the son of an architect, Maguire decided his path to prosperity was to become a chemist. That’s the field he planned to major in when he enrolled at North Carolina’s Duke University. But World War II military service interrupted his college stint, and by the time he returned to the States he had switched his interest to art, using his GI Bill benefits to enroll at New York’s Art Students League. His first professional projects were for a purveyor of pocket pulps including Hollywood Detective Magazine. Maguire soon moved up to painting book fronts, the art directors at publishers Ace, Pyramid, Signet, Avon, and others appreciating the fact that he could not only bring action and drama to his work, but was proficient at depicting beautiful women—required elements of paperback fronts in the wake of the war. Over the years, “Maguire painted dangerous dames, pagans, romantics, wantons, harlots, and more than a few victims of bad men,” according to his biographer, Jim Silke.

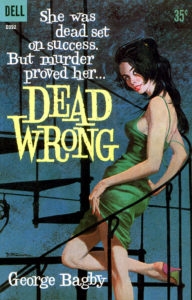

- Dead Wrong, 1960 – illus Robert McGinnis

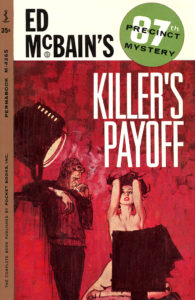

- Killer’s Payoff – illus Robert McGinnis

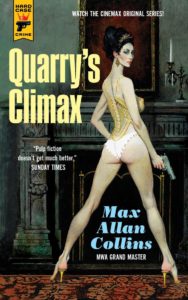

- QUARRY’S CLIMAX – Cover art by Robert McGinnis

Robert McGinnis (1926– )

If this were an endurance contest, the 92-year-old McGinnis would win it hands down. He premiered as a paperback artist in 1958, and today—six decades on—his signature species of lissome, lovely, and flirtatious/commanding women continue to appear regularly on Hard Case Crime paperbacks. As a youth in Ohio, McGinnis was encouraged by his mother to take classes at the Cincinnati Art Museum, and after high school he became an apprentice animator for Walt Disney Studios. He went on to study at Ohio State University, and in 1953 moved to the New York City area, where he exploited a contact with Mitchell Hooks to secure his earliest assignments painting crime-novel fronts. Now a Connecticut resident, McGinnis has turned out well over 1,000 covers, including many for books by John D. MacDonald, Carter Brown, Edward S. Aarons, Erle Stanley Gardner, Brett Halliday, Ed McBain, and Max Allan Collins. However, he’s also illustrated dozens of movie posters, promoting everything from the James Bond films to Dean Martin’s Matt Helm flicks.

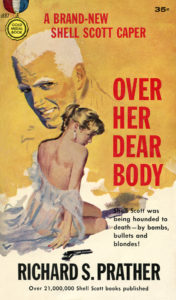

- Over Her Dead Body – illus Barye Phillips

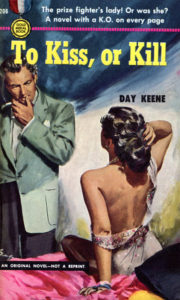

- To Kiss, or Kill – 1951, illus Barye Phillips

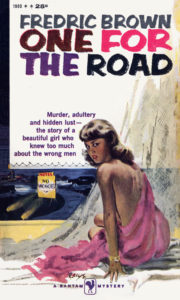

- One for the Road, 1959 – illus Barye Phillips

Barye Phillips (1924–1969)

For a guy who perished so young, in his mid-40s, Phillips left behind a remarkable profusion of softcover images. That’s because he was a publishers’ favorite, working quickly (reportedly completing as many as four high-quality paintings a week) and meeting his deadlines. Phillips is said to have initially demonstrated his talents with the Columbia Pictures advertising department, and to have gone from there to illustrating U.S. Army training manuals. He commenced taking on paperback chores in the early ’40s; and while he eventually brought his imaginative expertise to books released by Bantam, Avon, and Pocket, he was unusually prolific in churning out covers for Fawcett Gold Medal. Phillips’ eye-catching façades for Richard S. Prather’s Shell Scott gumshoe novels helped make them mammoth bestsellers, and he’s also warmly recalled for his labors on behalf of Fredric Brown, Jonathan Craig, Carter Brown, and Day Keene.

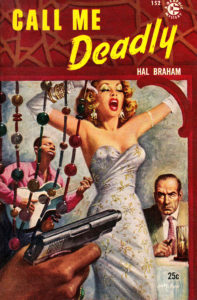

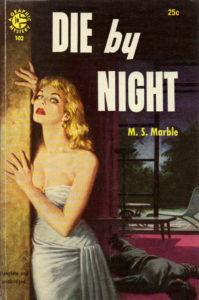

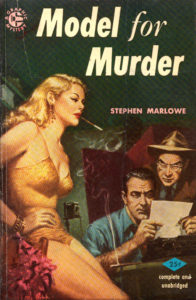

- Call Me Deadly, 1957 – illus Walter Popp.5

- Die by Night, 1955 – illus Walter Popp.3

- Model for Murder, 1955 – illus Walter Popp.2

Walter Popp (1920–2002)

It seemed only natural that Popp should’ve gone into art: his German-born father, Gustave Gutgemon, had become a successful New York City painter, who also taught architectural detail, while his mother worked in Gutgemon’s decorative-design studio. Following his 1940s U.S. Army service in war-torn Europe, Popp studied art and architecture in England before returning to America. He made his start as a freelancer painting covers and interior story illustrations for pulp magazines, and in fact kept up his work with periodicals well into the 1960s. Popp began soliciting jobs from paperback houses in the ’50s, proving that he could create fronts for hard-boiled crime yarns as proficiently as he could for Westerns and science-fiction adventures. During his more mature years, Popp and his wife, Marie (a trained fashion illustrator), collaborated on covers for Gothic romance novels and produced a limited series of romantic-fantasy scenes for art galleries.

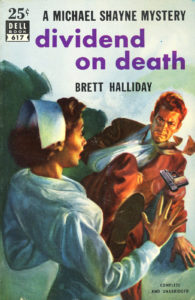

- Dividend on Death, 1952 – illus Robert Stanley

- The Groom Lay Dead, 1951 – illus Robert Stanley.4

- The Red Tassel, 1952 – illus Robert Stanley.2

Robert Stanley (1918–1996)

As was the case with so many of the folks profiled here, Stanley had to escape his roots if he was to make a name for himself. After leaving his Wichita, Kansas, birthplace and attending the Kansas City Art Institute, he labored briefly as a newspaper staff artist before making the leap to Manhattan in 1938. Stanley struggled to peddle his work to the pulps, but by the 1950s he had cracked the paperback illustration market. His big break came in 1951 when Dell, one of his principal clients, relocated its art department from Wisconsin to New York, and tapped Stanley—the company’s leading realist painter, known for his action-packed images and seductive woman—to give its line a fresh, handsome new look. Reports are that between 1949 and 1962, Stanley executed 242 covers for Dell, in many of which he featured versions of his redheaded wife, Rhoda.