It’s Halloween season, which, for many, means one thing: horror movies. Luckily, for year-round devotees of crime and noir, getting into the holiday spirit doesn’t require them to put aside their favorite obsession. As is the case with literature, horror movies and film noir go together like Nick and Nora. Or Freddy and Jason, if you will.

The connection is obvious: both genres, as we’ve come to know them, were spawned from German expressionist movements of the 1920s and have gone on to encompass a diverse array of subgenres within themselves. Both use suspense and mystery to play upon our emotions, even if their end goals are ultimately different. Both often (though not always) revolve around some form of violent transgression and lead down a path to doom.

While it’s true that a sharp distinction can be made between horror and noir, there is a long list of movies with one foot placed firmly planted on either side of that line. Here are 20 essential crime/horror films that either straddle said line, or else blur it so much that it becomes impossible to make any such distinction.

The Invisible Man (1933)

James Whale’s gleefully sinister adaptation of H.G. Wells’ The Invisible Man arguably shares more in common with silent-era serials about archvillains like Dr. Mabuse or Judex than it does fellow pre-code Universal monsters Dracula or Frankenstein, but the film still plays up the uncanny terror of a being in the malign presence of one you can’t see. Noir staple Claude Rains provides the voice of the phantom fiend, who embarks upon a “reign of terror” after a science experiment turns him invisible and drives him to madness, imbuing him with a seductive intelligence that would go on to influence any number of erudite monsters across future horror films.

The Leopard Man (1943)

Much like Universal in the 1930s, writer-producer Val Lewton is synonymous with the horror cinema of the following decade. The head of RKO Studios horror unit during that time, Lewton was given carte blanche when it came to the films he oversaw (so long as his films came in under budget and ran no longer than 75 minutes). In emphasizing mood and psychology over expensive makeup or costuming, he ended up producing some of the most artful and intelligent films from that period, in any genre.

Of those films, this bleak, but riveting mystery (directed by Lewton’s greatest collaborator, Jacques Tourneur) about a string of grisly murders in a small New Mexico village, is most revelatory when watched today. Not only does the first act contain one horror’s most tragic set pieces—in which a young girl is stalked by and falls prey to an unseen predator (which may or may not be an escaped leopard)—the film is also credited as one of the earliest explorations into the psychology of serial killers, long before this entered the public consciousness.

Dementia (1955)

A nameless young woman (Adrienne Barrett), who may have just committed a murder, wakes up in a strange hotel room and traverses a nameless city haunted by a variety of ghouls and phantoms while struggling to hold on to what’s left of her sanity. The depiction of violence (much of it overtly sexual) in this independent feature from director John Parker plays as shockingly ahead of its time; combined with a heavy layer of expressionist surrealism and Freudian symbolism, Dementia (released as Daughter of Horror) makes for a relentlessly frightening, often nauseating, utterly unforgettable depiction of the cyclical nature of trauma and abuse. The film’s influence can be seen in early American cult classics from the next decade, such as Night Tide and Carnival Souls, as well as later midnight movie staples Night of the Living Dead and Eraserhead.

Les Diaboliques (1955)

This classic French thriller from Henri-Georges Clouzot starts out as hardboiled noir in the vein of James M. Cain—the long-suffering wife and mistress of an abusive, despotic boarding school headmaster team up to murder him—before veering into full-fledged psychological horror, culminating in one of the most terrifying and influential scenes of all time. Les Diaboliques’ legacy extends beyond the finished film: it is believed that Alfred Hitchcock, who tried to option the original novel but was beaten to the punch by Clouzot, was attempting to one-up it when he made the next film on this list…

Psycho (1960)

And one up it he did. An adaptation of Robert Bloch’s novel from the previous year, Psycho’s abrupt shift from straight forward crime thriller to slow-burn horror roughly 1/3 of the way through stands as Hitchcock’s most devious and clever trick. The twist cemented it as the most iconic film in Hitch’s oeuvre—arguably the most iconic film in all of horror. If anything about the movie can be said to be underrated, it’s how solid and riveting a crime film that first third is, and we all should envy the original audience lucky enough to have been caught off guard when film suddenly shifted gears.

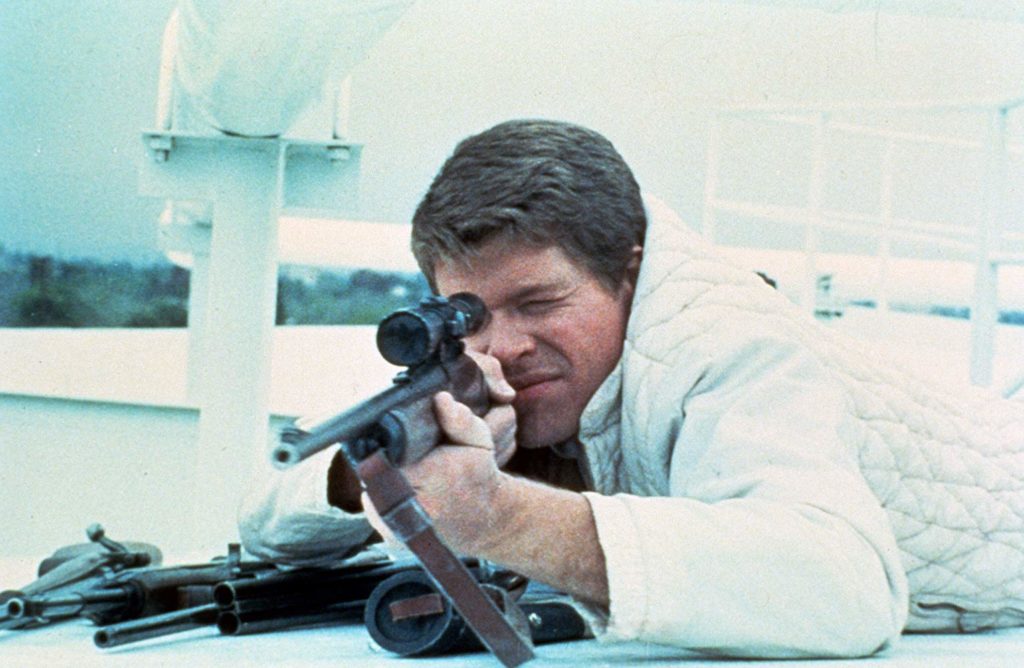

Targets (1968)

In his debut feature (made for Roger Corman’s American International Pictures), Peter Bogdanovich brilliantly cast Boris Karloff (who owed Corman two days of shooting from a previous project) as a worn-out horror film icon only a few steps removed from his real life persona. He then split the narrative with a seemingly unrelated story about a clean-cut young man (inspired by real life mass murderer Charles Whitman) who randomly embarks upon a mass shooting spree. Eventually, the dual narratives do intersect, resulting in a profoundly disturbing statement about the nature of idealized horror versus the banality of the real thing. In the decades since, Targets has grown even more prescient and unnerving.

The Wicker Man (1973)

The recent resurgence of folk horror has firmly re-established The Wicker Man as a foundational work beyond just its iconic twist ending. But the film—which sees a stodgy, conservative English police sergeant travel to the secluded island of Summerisle in search of a missing girl he fears the pagan inhabitants intend to use as a human sacrifice—is also a riveting police procedural, sticking to the tropes of that genre even as it subverts them. It’s that same subversion that ultimately lends the apocalyptic finale its full transgressive force.

The Beast Must Die (1974)

An eccentric and wealthy big game hunter invites a handful of guests—all of whom have some connection to a series of unsolved murders—to a weekend retreat at his heavily fortified English estate. But this is no ordinary drawing room murder mystery: the host suspects that one of the guests is not only a killer, but a werewolf.

This funky and all but forgotten Amicus production recently found its way onto horror and mystery aficionados radar thanks to a Syfy interview a with director Rian Johnson in which it got a shout-out. As noted in the interview, the film never quite lives up to its promise, but it still makes for a fun and spin on whodunits and werewolves alike.

The Eyes of Laura Mars (1978)

This late-Seventies thriller, which stars Faye Dunaway as a glamorous fashion photographer with a psychic link to a serial killer, is a fascinating American spin on the Italian giallo genre, as well as an immediate predecessor to the wave of slasher flicks that would soon flood the market. This makes sense, given that the screenplay was adapted from a spec script written by none other than John Carpenter, whose breakout hit Halloween (which shares much of this film’s DNA, including roving POV shots from the killer’s perspective) would come out only a few months later. Meanwhile, the film’s seedy Time’s Square setting makes it as perfect a companion piece to gritty New York crime classics like The Taking of Pelham 123 and Looking for Mr. Goodbar as it is to Halloween or Friday the Thirteenth.

Fascination (1979)

French filmmaker Jean Rollin was known for his erotic, phantasmagoric spins on the vampire mythos (as well as other horror staples), and among his most well-regarded work is Fascination, a story about a thief on the run from his double-crossing gang, who seeks refuge in an ancient castle in the French countryside. There, he runs across two gorgeous sisters and takes them hostage, only to discover they harbor a strange and dangerous secret. The criminal plot line is eventually dropped as the film unfurls headlong into gothic romance, but the setup lends a modern edge to the film’s baroque trappings, while also leading to the its most iconic scene, in which French bombshell Briggitte Lahane dispatches several gang members with a scythe.

Tenebrae (1982)

The Italian giallo genre sits at the perfect nexus between crime and horror, incorporating essential elements from grand guignol theater, detective mysteries, gothic romance, Hitchcockian thrillers and slasher films. And when one thinks of giallo, they likely think of Dario Argento. Although Tenebrae marked Argento’s return to the genre after a run of supernatural horror films, its meta-textual framework (the series of brutal murders at its center revolve around a commercially successful mystery novelist) allows him to comment upon his own body of work, making this perhaps his most personal film and the ultimate statement on the giallo genre.

Wolfen (1981)

This early ‘80s genre mashup—part dank urban police procedural, part supernatural monster movie, part shadowy sci-fi technothriller—is a strange beast indeed. A series of animalistic killings across the city leads a dogged detective and skeptical criminal psychologist to uncover a vast conspiracy involving private security firms, New York City’s Native American underground, and an ancient race of wolf gods. You’d think that a film with so convoluted and bug nuts a plot would be a psychedelic romp, but Wolfen plays everything 100% straight. This makes for a heady, hypnotic—but sometimes tedious—cult oddity. It’s not a classic by any means, but it’s definitely worth a watch if you like weird hybrid films.

Q—The Winged Serpent (1982)

A doomsday cult summons an ancient Aztec God—the dread flying serpent Quetzalcoatl—to modern day New York, where it begins devouring people at random, leading to a mass panic and a city-wide police manhunt. At the same time, a down on his luck jazz pianist and professional getaway drive named Jimmy Quin (Michael Moriarty), fresh off a botched bank job, stumbles upon the beasts’ lair hidden high atop the Chrysler building. Suddenly, Jimmy’s the most important man in all of New York, and he attempts to leverage his information with the city for a clean jacket and nifty little fortune, all while the beast continues to prey upon the city.

Director Larry Cohen was a master at imbuing ultra-pulpy material with a sharp, cynical intelligence and fiery social conscience. Never did this particular alchemy coalesce better than in Q—The Winged Serpent, which might best be described as Godzilla meets Dog Day Afternoon.

Angel Heart (1987)

Private investigator Harry Angel (Mickey Rourke) is hired by the malevolent, mysterious businessman Louis Cypher (Robert De Niro) to track down a missing amnesiac named Jonny Favorite. His search leads him to New Orleans, where he soon finds himself lost in a nightmare world of voodoo, Satanic worship and ritual murder, all of it leading to a shocking revelation that is at once entirely obvious (just look again at those character names) and effectively devastating.

Thanks to its troubled production, mostly negative critical reception, and the controversy surrounding co-star Lisa Bonet’s explicit sex scenes (which initially earned it an X-rating), Angel Heart has remained a somewhat notorious film, although over time it’s come to be rightly regarded as one of the artful and intriguing horror-mystery films of its decade.

Maniac Cop 2 (1990)

Written by Larry Cohen and directed by exploitation maestro William Lustig, the Maniac Cop films are the ultimate in modern pulp horror, mixing the gritty police procedural with the zombie and slasher genres to create one of the most underrated slasher franchises of the late ‘80s/early ‘90s.

The premise of an unkillable zombie cop who helps criminals and slays innocent civilians is as brilliant a hook as it is a trenchant commentary on America’s police culture. In this era of heightened tensions between police and the public, it’s no wonder the franchise is being rebooted for HBO (showrunner Nicolas Winding Refn promises “an unadulterated, action-packed horror odyssey…[and] a strong commentary on the decline of civilization.”).

I recommend getting a jump on the new series by diving in to the original trilogy. While each of the films in the franchise is worth a watch, part two gets the edge thanks to a handful of bonkers set pieces and stunt work.

The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

Although horror movies have remained popular since the advent of cinema, the genre has never been able to shake a certain air of disrepute. Never was this more prevalent than in the critical reception to Jonathan Demme’s massively successful adaptation of Thomas Harris’s bestseller, during which many an observer attempted to classify it as a straight thriller, despite the various stretches of the film that operate on pure horror logic, because God forbid a horror movie win Best Picture. Petty as such distinctions seemed at the time, they look even more ridiculous now, as the character of Hannibal Lector has gone on to become as iconic a boogeyman as Dracula or Michael Meyes.

Given how ensconced the film is within the popular culture, I don’t have much to add, so I’ll use this spot to also recommend Manhunter, Michael Mann’s artful, dreamy adaptation of Harris’s earlier Lector novel Red Dragon from 5 years prior. While by no means an obscure film, Manhunter isn’t nearly as well-known as Silence (or, for that matter, Brett Ratner’s later and much inferior Red Dragon adaptation), even though it’s just as good. Consider this spot a twofer.

Seven (1995)

After Silence of the Lambs, there’s probably no modern serial killer drama more influential that David Fincher’s Seven. Like its predecessor, Seven encompasses both noir and horror; in fact, it reaches further down into both in order to present a truly nightmarish universe, what noir novelist Megan Abbott perfectly describes as “an Ellroy story set in a David Lynch world.” Even accounting for the film’s not altogether welcome influence—to this day, many a bad serial killer or torture porn movie has attempted to ape its grimy aesthetic and stylized violence, without bothering with to come up with a good story first—its nihilistic power remains nearly unmatched.

Tales from the Hood (1995)

Of the explosion of ‘90’s Hood movies—politically charged crime dramas centered around the plight of black (or, less frequently, Hispanic) inner city communities—one of the most underrated is this darkly comic, righteously angry anthology film, which used a horror framework to examine a number of political and social issues, including police brutality, domestic abuse, the legacy of slavery and gang violence. Tales from the Hood was largely dismissed at the time by white audiences and mainstream critics, although it quickly cemented itself as a cult favorite of the era. Recent cultural and historical evaluations of black horror cinema has led to a much-deserved critical reassessment.

From Dusk till Dawn (1996)

This collaboration between screenwriter Quentin Tarantino and director Robert Rodriguez, made at the height of their somewhat annoying wunderkind statuses, starts out as a straightforward crime road movie before suddenly introducing Mexican vampires about halfway through. While this shift makes it an obvious choice for this list, I was initially hesitant to give it a spot, rather than Katheryn Bigelow’s similar Near Dark, which is widely heralded as the far superior neo-wester-noir vampire flick (consider this sport another another twofer).

Ultimately, I decided to go with From Dusk till Dawn for one reason: throughout the film, characters continually refer to El Rey, the mythic Mexican city of outlaws described in the notorious final chapter of Jim Thompson’s classic 1958 crime novel The Getaway. Although none of the horror in From Dusk till Dawn comes close to matching Thompson’s description of El Rey (think Kafka’s The Castle meets Cannibal Holocaust), the homage no doubt led some viewers to discover the hardboiled god of postwar noir (I speak from personal experience).

Lost Highway (1997)

A large part of what makes the films of David Lynch so singular is their inability to be categorized or put into genre boxes. Still, his dreamlike visions are steeped in the language of horror and noir. I could have placed almost any his films—Eraserhead, Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, Mulholland Drive, Inland Empire—in this spot, but I choose Lost Highway because A) I feel that it is the most overt in its use of film noir tropes, (what with its use of the doppelgänger and femme fatale archetype, gangland intrigue, and anachronistic 50’s costuming and décor), B) its abrupt and disorienting narrative shifts make it a good companion piece to several of the other films on this list, and C) no horror movie ghoul or fiend is nearly as terrifying as The Mystery Man.