“To say little and convey much”—that was how, in a 1949 letter to his publisher, Raymond Chandler began his defense of the aesthetic he and other crime writers were using to put their stamp on American letters. Chandler called it the “objective method” and said that if you know how to use it, “you can tell more in a paragraph than the probing writers can tell in a chapter.”

Now that’s not to say that the annals of crime literature haven’t included many fine and probing writers or its share of door stopping classics from the likes of Dostoevsky and Ellroy. Still, crime and mystery writers have long excelled at (and taken pride in) telling stories within tight confines. These books come in all varieties and inclinations. Some rely on dense atmospherics; others lean on taut dialogue and swift action; then there are the effervescent tales where the prose lacks all spareness and lights up like a roman candle, then quickly snuffs out the flame. Whatever the modus operandi, fine crime writing can hit you hard and quick and leave a mark.

To celebrate the art of brevity, we’ve rounded up a list of 25 compact crime and mystery reads—noirs you can (and mostly likely will) read in the course of an afternoon (or an evening, or even a morning, whatever time suits you). Don’t let the page count belie the ambition or the achievement. These are books of impact, import, and verve. Happy reading.

James M. Cain, The Postman Always Rings Twice

Banned in Boston! Cain’s masterpiece was a sensation on first publication and has more or less stayed current to the culture ever since. A drifter breezes into a sleepy California town, takes a job at a diner, and begins a torrid affair with the joint’s mistress. Their passion goes dark and you probably already know the rest, or soon will. Cain’s noir is pitch-perfect and an absolute classic, a must read for anyone interested in suspense, 20th century literature or good books.

(Further reading: Laura Lippman on James M. Cain’s transgressive noir.)

Dorothy B. Hughes, In a Lonely Place

Allow Megan Abbott, modern-day master, to sum up the effects of reading this one: “After reading In a Lonely Place, you find yourself looking, with a newly gimlet eye, at every purported femme fatale, every claim of female malignancy and the burning need of noir heroes to snuff that malignancy out.” (From Sarah Weinman’s anthology, Women Crime Writers of the 1940s & 50s.)

Dolores Hitchens, Fools’ Gold

(Another selection from Weinman’s Women Crime Writers of the 1940s & 50s—probably best to just make your way through the whole collection.) Heedless teenagers wade into a sinister plot in Hitchens’ 1958 noir, a dark portrait of midcentury American restlessness. Hitchens’ deserves an even grander reputation, but this story did find a level of fame when Godard adapted it as Bande à part.

Raymond Chandler, Playback

The last novel written by the crime master, and the last investigation of the iconic Marlowe. In Playback, Marlowe is hired to track down a woman on the run, but as usual, nothing is quite so simple. Many consider Playback to be lesser Chandler, but the story has an undeniable momentum, and the unusual (for Chandler) coastal small-town setting allows the author to flex a few surprise muscles. (Although, to be perfectly frank, if you only have one afternoon to spare for Chandler—blaspheme, I say—go ahead and spend the extra hour on The Long Goodbye.)

Georges Simenon, The Widow

Simenon, the king of the after-dinner Franco-mystery and among the most prolific storytellers who ever lived, was capable of some truly dark and disturbing literature, too. In The Widow, a hired hand moves into a rugged farmhouse and disrupts the terrible tension already filling the air. It’s another classic tale of ill-fated drifters, a psychological thriller that won’t soon leave you be.

Jim Thompson, The Getaway

A seminal bank heist / fugitive story, Thompson’s crime-gone-wrong novel masquerades as a taut page-turner but eventually reveals itself as something much stranger and more haunting. A pardoned man puts together a team (including, yes, a librarian) for a bank job, which of course goes wrong and sets them off on a hallucinatory road trip where reality comes untethered.

Margaret Millar, Beast in View

The opening chapter of Millar’s Beast in View stands against any in the modern annals of literature. A woman receives a mysterious phone call; the caller is persistent and menacing and soon draws her into a spiral of compromise and vice. Millar’s popularity is back on the rise of late, as current-day readers see the origins of their beloved psychological thrillers in her work.

(Further reading: you can check out that famous first chapter right here on CrimeReads.)

Jean-Patrick Manchette, The Prone Gunman

Quite possibly the crowning achievement of the godfather of French neo-polars (the socially cynical, hard boiled movement that swept through French literature in the 1970s), The Prone Gunman is a bold aesthetic statement and a story of brutality, violence, and regret. Manchette can accomplish in a page what other writers might do in a novel, and the effect is electrifying.

Graham Greene, The Quiet American

Greene’s 1955 novel proved prescient on the doomed Western involvement in Southeast Asia and posed a sharp critique of the US’ growing imperial ambitions (later landing the author on the FBI’s radar for potential subversives/persona non grata). This is one of the sharpest and most deeply felt thrillers of Greene’s long and storied career.

Gabriel García Márquez, Chronicle of a Death Foretold

“On the day they were going to kill him, Santiago Nasar got up at five-thirty in the morning to wait for the boat the bishop was coming on.” Thus begins (in the English translation from Gregory Rabassa) one of Garcia-Marquez’s great achievements, a compact and agonizing portrait of a village wedding and the cruel momentum of fate.

George V. Higgins, The Friends of Eddie Coyle

A master class in what dialogue can accomplish, and one of the best-paced, most entertaining crime novels ever published. Eddie Coyle is a woebegone Boston gun dealer between a rock and a hard place, facing serious jail time or the prospect of finding a crime ring to give up. Higgins’ novel ushered in the 70s era of gritty, cynical crime stories and made for one hell of a movie.

Chester Himes, Cotton Comes to Harlem

Himes is enjoying something of a renaissance thanks to Lawrence P. Jackson’s new biography (not to mention the efforts of contemporary authors like James Sallis). Cotton Comes to Harlem, probably his best known work, is packed tight with style, verve, and a macabre wit, unfolding the story of an investigation into a string of murders and a shadowy cotton operation based out of Harlem and purporting to send young black men back into fields in the South. (The investigation is conducted by Himes’ standbys, “Grave Digger” Jones and “Coffin Ed” Johnson.)

Ross Macdonald, The Galton Case

This is Ross Macdonald at his finest: a vanished heir, a family fortune, a gaggle of hustlers hiding their craven plots beneath a thin veneer of society. A non plus ultra Lew Archer story.

Roberto Bolaño, Distant Star

Bolaño’s underappreciated masterpiece begins with a poetry seminar and a grisly murder, then spins out into a wild story of right-wing militarism, the LatAm diaspora, and cold case investigation via literary journals. All that in about the time you’ll need to read the first section of 2666.

Fuminori Nakamura, The Thief

Nakamura’s anonymous pickpocket navigates the streets of Tokyo dressed to the nines and lifting what he pleases off unassuming marks, until his old partner shows up with a proposition. Nakamura has few equals for style, and in The Thief, he teases out a sense of dread to match the literary flare.

Ruth Rendell, The Thief

Haven’t had enough The Thief in your day? Good, because there’s more. Rendell’s taut psychological study looks at a compulsive ‘thief’–a woman whose instincts guide her always to taking what isn’t hers. A chance encounter shakes the woman to her core, with chilling consequences.

Patrick Modiano, Honeymoon

The French Nobel laureate’s novels, compact as a rule, rely on atmospherics and tend to leave you with the unsettling feeling that the truth is just out of reach. Honeymoon takes Modiano’s preferred perspective–a man looks back on a strange adventure from his youth. This time, the adventure unfolds on the Riviera; a young man falls in league with a glamorous couple on the run from occupied Paris. The plot is riveting, but the nature of time and memory are Modiano’s true subjects.

Walter Mosley, Gone Fishin’

Mosley’s standalone tells the backstory for the dark deed that bonded Easy Rawlins and Mouse Alexander. It’s among Mosley’s most compact works, but with the usual pathos and poignancy.

Megan Abbott, Queenpin

Abbott pumps new life into a classic setup–the aging mobster teach a young acolyte the secrets of the underworld–with an aging mobster queen, Gloria Denton, who takes her young student on a tour of tracks, casinos and cons. This is a deft and wildly compelling story of bonds and betrayal from a contemporary suspense master.

Jo Nesbo, Blood on Snow

Nesbo’s Olav is part Luca Brasi, part Michael Corleone, and a hell of a storyteller. Nesbo is most famous for his Harry Hole novels, but he knows how to write a taut, compelling standalone, too. This one is the story of a conflicted mob enforcer on the mean streets of Oslo.

Laura Lippman, The Girl in the Green Raincoat

(Originally published in serial form over 2008-2009 in The New York Times.) Lippman’s longstanding sleuth, Tess Monaghan, is pregnant, restless, and worried about her prospects. When a mysterious young woman comes into the neighborhood and promptly disappears, Tess finds her new cause, with more than a few echoes of Rear Window and Hitchcockian suspense.

Eileen Chang, Lust, Caution

The tension runs thick in Chang’s swift tale (sometimes classified as a story or novella but which we’ll call a novel for the sake of argument). A young actress takes on the job of assassinating a collaborating official in Japanese-occupied Shanghai. Chang’s prose is at once sumptuous and restrained, and the atmosphere is one you won’t soon forget after reading.

Daniel Woodrell, Under the Bright Lights

Woodrell’s debut proved an early mastery of the form and a penchant for atmospherics. In a ramshackle bayou town, Rene Shade navigates the pool halls, hustler hangouts and cajun-controlled rackets in the hopes of solving a racially charged murder. Woodrell would go onto fame for his Ozark novels, but his version of Mississippi River swamp crime will haunt you for a long while.

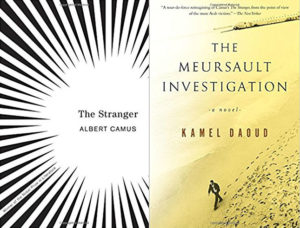

Albert Camus, The Stranger / Kamel Daoud, The Meursault Affair

Read these two in tandem and you won’t be sorry. Camus’ noir classic serves as the jumping off point for Daoud’s modern reimagining, the latter told from the perspective of Harun, the brother of the anonymous “Arab” killed by Meursault on the beach in Algiers. While Camus’ work stands as a testament to the chiseled down noir style and existentialist philosophies, Daoud’s is a worthy rejoinder exploring the perils of colonial identity and the traumas of the unseen.