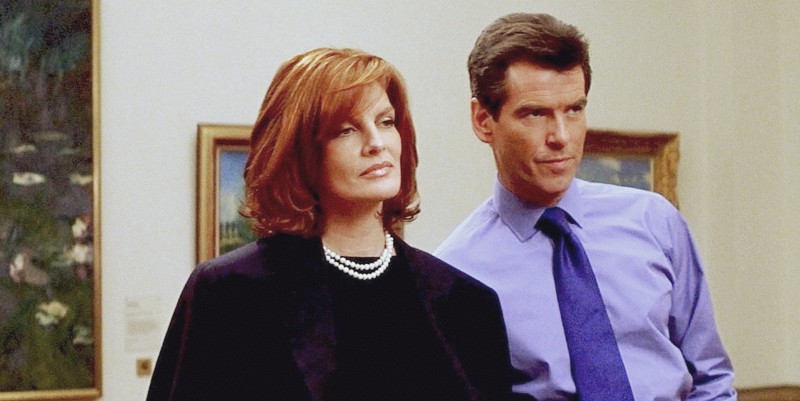

The 1999 version of The Thomas Crown Affair inspired a garden variety of art heist novels. Pierce Brosnan, cast as the billionaire, steals Monet’s San Giorgio Maggiore at Dusk from the Metropolitan Museum for the thrill of executing the theft. I sat on the edge of my chair as I watched Crown pull off this caper, get away with it and then return the now-disguised stolen painting to its very spot on the museum wall. The film was loosely based on Eric Ambler’s novel The Light of Day (1962) but screenwriters Leslie Dixon and Kurt Wimmer reimagined the narrative. Thomas Crown presents as an elegant, confident man. Not your typical art thief. Yet of the seven authors in this article, only Ian Rankin’s plot revolves around privileged men with a plan to steal art for the fun of it.

The other six writers portray art heists as serious business, often with dangerous consequences. Their villains are mostly greedy art collectors who crave certain paintings to make them feel important. Art collectors who hire others to steal art for them is not new. Back in 1664 Cardinal Scipione Borghese, nephew of Pope Paul V, lusted after every Caravaggio painting for his collection. He had his uncle accuse Caravaggio’s teacher, Cavalier d’Aprino, of owing exorbitant papal taxes so that Caravaggio’s early masterpiece, Boy with a Basket of Fruit, as well as 105 other paintings, could be confiscated and then delivered to Borghese’s palatial home.

Stolen art is a much bigger business than I imagined. Interpol and UNESCO list art theft as the fourth largest black market in the world, after drugs, money laundering and weapons. Interpol data from March of 2018 showed that the black market for art was worth between $4-$6 billion. While thefts of high profile paintings, such as Emil Nolde’s The Scream or Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, may garner international attention, it is the lesser-known masterpieces that disappear into the ether. Famous art is now almost impossible to sell. But there are almost 100,000 stolen pieces of art listed in the Art Loss Register and many of them are not well-known. That’s enough material to keep novelists occupied with stolen art shenanigans for years to come.

Ian Rankin, Doors Open

Ian Rankin, the Scottish mystery writer, may be most widely celebrated for his 25 dark novels featuring Inspector John Rebus, but his playful side erupts in his standalone novel Doors Open (published in 2008). The story begins in an Edinburgh art auction where three friends reconnect. Mike Mackenzie made a fortune with his software company and is retired and now bored. Robert Gissing is an art professor who is miffed by the fact that so many pieces of art are hidden away in private collections, unavailable to the general public. Alan Cruickshank is a successful banker with a taste for art that he can’t afford. Gissing suggests that it would be enormous fun to “liberate” a few priceless works of art from the National Gallery’s storage warehouse. Mackenzie’s old high school mate turned local crime boss is brought into the scheme and the game is on.

Daniel Silva, The Rembrandt Affair

Daniel Silva has taken the world of art theft novels to a new level with his endearing protagonist, a smart and daring art restorer named Gabriel Allon. As a reader I immediately connected with Allon’s adventurous spirit, following his travels all over the world to recapture stolen art while he helps to solve the murders associated with these thefts. Silva employs current events and does extensive research so that we readers are in the thick of it wherever Gabriel Allon may be.

So far Silva has published 20 novels in his New York Times bestselling series, writing one novel a year since 2000. His writing is notable for its crisp dialogue as well as its refreshing lack of extreme violence and foul language. In its place, Gabriel Allon, whose life has been blessed with love and dogged with family tragedy, suffers regrets and sleeps little during an operation.

The Rembrandt Affair (published in 2010; # 10 in the series) revolves around an “unknown” painting of Rembrandt’s mistress (Hendrickje Stoffels). Gabriel and his beautiful wife Chiarra are now retired and living in Cornwall when he learns through London art dealer Julian Isherwood of the murder of another restorer, Christopher Liddell, at Glastonbury, and the disappearance of the Rembrandt he was restoring. Armed with only a few photographs and notes from the art restorer, Gabriel sets out on a journey to trace the painting through its provenance, beginning in Amsterdam, where it was first sold to cover the artist’s debts, then acquired by a diamond merchant, and later seized by the Nazis and placed in safe keeping. When the trail shifts to Argentina, a shadowy organization moves in, and Gabriel and Chiara narrowly escape with their lives.

Iain Pears, The Bernini Bust

Iain Pears, an English novelist, journalist, and art historian, has a PhD in Philosophy from Oxford. He has written seven art mystery novels as well as other novels and books. His plots tend to be more intricate than most art heist novels, although his style is light-hearted and more colloquial than his other literary works. Pears is the only author on this list who wrote all but one of his art heist novels before the “The Thomas Crown Affair.”

The Bernini Bust (published in 1993) is the third in the Jonathan Argyll series. It includes tax fiddles, murder, fraud, adultery, theft, suspects framing each other for crimes, eavesdropping, and firing people. Most of the action takes place in Los Angeles where the bumbling Argyll tries to deliver a valuable Titian painting to a minor Californian museum for an inflated price while he hopes to receive a handsome $4M for his trouble. The art museum was founded by billionaire Arthur Moresby as a tax write-off. But nothing works out as planned as a lost Bernini bust of Pope Pius V shows up at the same museum. Moresby is murdered. The art connections mystify LAPD homicide detectives who are more used to drug gang killings. There is an Agatha Christie-style ending that is lots of fun.

Jeffrey Archer, False Impression

Jeffrey Archer, a British peer of the realm who was once a convicted perjurer, is good at creating characters you hate and also heroes whom you really want to win. He’s been enormously successful as a thriller writer and owns a villa in Majorca called Writer’s Block. False Impression is his only art heist novel (published in 2005). The novel revolves around Bryce Fenston, a villainous banker whose shady practices include robbing wealthy clients of their famous art. When they try to sell some of their paintings in order to pay their debts, he has them murdered and sacks their estates during the long probate process. Anna Petrescu, a former Sotheby’s art assessor, is hired as Fenton’s assistant without her knowing about his sinister schemes. Jack Delaney, an intrepid FBI agent, begins investigating the bank’s nefarious activities, including its connection to a cold-blooded knife killer. Archer is as skilled educating readers about the nuances of high-end art collectors as devising intricate plots.

Carson Morton, Stealing Mona Lisa

Multi-talented Carson Morton (writer, musician, children’s book author and illustrator) is a man obsessed with the thefts of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. He has written two art heist novels on the subject. The first one, Stealing Mona Lisa, was a big success. It was published in 2011, exactly one hundred years after the actual crime took place at the Louvre. The story follows Eduardo de Valfierno, a strangely likeable charlatan who makes his living selling forgeries of masterpieces to clients who believe they are receiving the original paintings. Valfierno begins his career in his birthplace of Buenos Aires, but he assembles his team of con artists in 1911 Paris for their final and most ambitious theft, one that he hopes will enable them to leave the game forever: Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. Morton’s descriptions of early twentieth century Paris are cinematic and his language is poetic at times. My favorite character, Valfierno’s partner-in-crime Julia, is a beautiful and savvy American pickpocket. She can be clever and funny, but I also took her seriously as Julia saves the other con artists more than once. Morton is a good storyteller and he kept me guessing until the end.

Jennifer S. Alderson, The Lover’s Portrait

Jennifer S. Alderson, an international backpacker and travel writer from Seattle, moved to Amsterdam as an adult, where she studied art history. Her art heist novel, The Lover’s Portrait: An Art Mystery, was published in 2004. I wondered if the story was semi-autobiographical as Alderson’s female protagonist Zelda Richardson is also a gutsy, resilient and ethical art history student. What’s clear is that Zelda’s in over her head when her search for truth entangles her in a 70-year old web of stolen paintings, blackmail and murder. A fictitious gallery near a small canal is the main scene for the novel where two separate people claim the same Nazi-stolen painting. One of the claimants is a fraud who will go to any lengths to get the painting. The mystery surrounding the painting, Irises, and its uncertain provenance is enhanced by present day Amsterdam’s charming atmosphere. I wanted Zelda and her likable sidekick Frederich to find a way for their legitimate client, Rita Brouwer to obtain her rightful inheritance.

Robert Brown Parker, Painted Ladies

Robert Brown Parker, the beloved New York Times best-selling author of 38 novels starring Spenser, the fictional Boston detective, sadly passed away in 2010. Parker’s 39th novel Painted Ladies was published posthumously. It was Parker’s first and last art heist novel, about a brilliant, but unknown, Dutch painter whose painting was stolen from the fictitious Hammond Museum. The witty and sophisticated Spenser accepts his latest case to provide protection during a ransom exchange for this stolen painting. I thought the charm of this novel is that it doesn’t try to be anything more than it is. As in Parker’s other Spenser novels I loved the banter between Spenser and the police. Spenser learns that his client, renowned art scholar Dr. Anton Prince, was once a married skirt-chaser who harbored secrets about his past, and that Nazi art thefts during WWII may be related to the Hammond Museum burglary. The Nazi angle is especially troubling because killers with replicas of concentration camp tattoos make numerous attempts on Spencer’s life. Parker’s cat and mouse games never disappoint.

***