This Sunday will mark 100 years since the end of World War I on November 11, 1918, an occasion still celebrated (in France, Britain, and elsewhere) as Armistice Day. Almost four years of battle across Europe had cost the lives of more than 8 million soldiers, with another 21 million of them wounded, and tens of thousands left with “shell shock”—what is known today as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The map of the continent was drastically altered by that catastrophic clash of powers, with whole empires vanishing and the war’s economic fallout being felt long after the bombing had quit and front line trenches were filled in. Staggered by what was originally called the Great War, politicians, authors, and other idealists declared it “the war to end all wars”—a promise broken two decades later by the onset of World War II.

The war changed writers’ approaches to horror fiction, but even more profoundly affected mystery fiction, ushering in its so-called Golden Age. Still, years passed before many mystery-makers felt emotionally prepared to revisit the war years. Yes, Hercule Poirot’s sidekick, Captain Arthur Hastings, had been invalided home from the Western Front, and Lord Peter Wimsey was left with PTSD after being virtually buried alive by a shell blast. But it wasn’t until 1928’s The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club that Dorothy L. Sayers made wartime remembrance crucial to her plot, and only in 1937 did war hero Henry Wade (aka Henry Lancelot Aubrey-Fletcher) employ an episode of battle-born shame as a central ingredient in The High Sheriff. Thankfully, time’s passage has made it easier for authors to incorporate the events and ramifications of World War I in their fiction.To commemorate this weekend’s centenary, I’ve compiled a variety of crime and espionage stories whose action occurs within the first half-decade of the war’s finish.

The Ways of the World by Robert Goddard (2013)

It’s the spring of 1919, and 27-year-old James “Max” Maxted, previously of the Royal Flying Corps, is finally back in England following two years of service on the front and another 18 months spent in a German POW camp. Together with Sam Twentyman, his friend and erstwhile airplane engineer, he hopes to launch a flying school on his family’s ancestral estate. However, news that his diplomat father, Sir Henry Maxted, has tumbled to his death in Paris amid deliberations over what will become the Treaty of Versailles, obliges Max to delay those plans. He and his scandal-wary elder brother travel to France to retrieve their sire’s remains, but in the course of it, Max grows doubtful of police speculation that Sir Henry’s demise was a “bizarre and undignified accident” suffered while he was covertly observing his “très jolie” mistress. Despite Max’s dearth of intelligence-gathering savvy, he’s “cool-headed and courageous,” and manages (with Sam’s aid) to unearth a panoply of unsavory players—including an amoral American dealer in secrets, a seductive Russian bookshop employee, a scheming official with Britain’s Foreign Office, and a German spymaster—who might help answer questions surrounding Sir Henry’s fate. Could the diplomat’s death have had to do with the explosive contents of his safe deposit box? Dubious allegiances, the intervention of an elusive Arab boy, and a hired assassin all figure into this dramatic and atmospheric yarn—the opening installment in a trilogy.

The Second Rider by Alex Beer, translated by Tim Mohr (2018)

Like the city he serves—Vienna, former capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire—Inspector August Emmerich has been brought low by the Great War. He has a wounded leg that’s left him ingesting pain meds such as heroin, and that he fears will curtail his dream of joining an elite major-crimes unit. His lover has just learned her husband didn’t die in battle after all, and she’s decided to return to his side. And Emmerich has been saddled with a naïve partner, Ferdinand Winter, who he fears will spoil his opportunities for recognition as a crime solver. Actually, the inspector’s inclination toward disobedience and obstinacy might be equal handicaps in that regard. He and Winter are tasked with crushing a smuggling ring that operates partly out of the city’s sewers and is run by one of Emmerich’s boyhood pals, Veit Kolja…but the inspector is more interested in pursuing a seemingly unconnected sequence of deaths, which have been passed off as suicides or the consequence of mishaps. He’s sure those men were murdered, but can’t ascertain how they knew each other, or why their mouths were stained yellow. Emmerich’s resolve to prove his conclusions will result in his becoming a wanted man, and ultimately his turning for assistance to Winter and Kolja. Beer’s character development and portrayal of postwar Vienna’s economic divisions may push her English-language debut onto many best-of-the-year book lists.

River of Darkness by Rennie Airth (1999)

Set in South East England in the summer of 1921, this persistently surprising whodunit introduces Scotland Yard inspector John Madden, who’d left the force “some years before” after losing both his spouse and infant daughter to influenza, and then taking up arms on the bloody battlefields of Europe. He’s since returned to the Yard, but is a changed man—taciturn and wearily pragmatic, yet oddly hopeful. In River of Darkness, Madden investigates the slaughter of a well-respected family in their Surrey mansion. An unidentified bladed instrument did the damage, but nobody can identify the motive. Not even the 5-year-old girl who witnessed that butchery and now lives in traumatized silence, compelled to draw, over and over again, the same crude image: what looks like a balloon with a string and two eyes. After reasoning that the perpetrator is an ex-soldier, who stalks his prey from military-style dugouts, Madden links the Surrey slayings to prior unsolved atrocities. His success, though, is threatened by an arrogant, preening Yard superintendent who contrives to take over the case. The decision by South Africa-born journalist/author Airth to parallel Madden’s assiduous probe with long, affecting looks into the quotidian lives of the gunman and his next set of victims prepares us for what savagery is to come, while exacerbating the horror of its impact when it arrives.

A Test of Wills by Charles Todd (1996)

This is one of the books that made me a follower of historical mysteries. Its protagonist is Scotland Yard Inspector Ian Rutledge, who survived being buried alive during the disastrous Battle of the Somme, but came home shell shocked, his head occupied by the omnipresent, mocking voice of Hamish MacLeod, a young Scottish soldier he’d had executed at the front for refusing to fight. Now, every fictional detective needs somebody with whom to discuss his or her cases, but it’s rare to find that conversational comrade trapped inside the sleuth’s own psyche. A Test of Wills—the initial installment in a long-running series composed by a mother-son writing team—sends Rutledge, in 1919, to the county of Warwickshire, where he’s to apprehend whoever fatally shot retired Colonel Charles Harris from his horse while he was out for his morning ride. Locals believe chronic troublemaker Bert Mavers committed this deed, but talk of a recent quarrel between the squire and Captain Mark Wilton, the well-connected fiancé of Harris’ ward, places him under a dark cloud, too. The case is full of minefields and hints of conspiracy, and unfortunately for Rutledge, an important witness is another shell-shock survivor, whose mental decline makes him unreliable—and perhaps an ill omen of what the inspector’s own future may bring. While the puzzle elements and character depictions are engaging, it’s Rutledge’s adversarial but ultimately useful relationship with his personal ghost, Hamish, that makes this and subsequent novels in the series most intriguing.

A Gentleman’s Murder by Christopher Huang (2018)

Echoing the style of Golden Age mysteries, this debut novel takes place in 1924, primarily within the confines of the Britannia, a posh London gentlemen’s club with a membership of war heroes—or at least men who lived through their battlefront experiences. Among those is Eric Peterkin, an English-Chinese lieutenant who served with the British Army in Flanders and now evaluates manuscripts for a publisher of detective novels. Men from Peterkin’s lineage have long cherished the peace and respectful camaraderie of the Britannia. But both of those qualities are upset when a new member, a conscientious objector named Albert Benson, is slain after having bet that one of his fellow Britannia habitués, Captain Mortimer Wolfe, couldn’t break into the club’s vault and remove the contents of his safe deposit box—articles that Benson told Peterkin could be used to “right a great wrong from the past.” The next day, Wolfe smugly displays a pair of surgical scissors Peterkin knows were in Benson’s box, but he denies the presence there of other curious items. An inspection of the vault finds Benson stabbed with a letter opener belonging to the Britannia’s president, and Peterkin promptly assumes responsibility for solving Benson’s murder as well as continuing the deceased’s pursuit of justice. Huang deftly exposes the histories and weaknesses of his stiff-lipped suspects, while his man Peterkin confronts their opposition not only because of his intrusive questions, but as a result of his mixed-race heritage.

The Three Hostages by John Buchan (1924)

Anyone remotely familiar with Scottish politician/author John Buchan knows he penned The Thirty-Nine Steps. However, that 1915 “shocker,” in which adventurer Richard Hannay foils a German plot on the eve of World War I, was followed by a quartet of sequels; The Three Hostages is the fourth Hannay tale, but the first to be set post-armistice. It’s the early 1920s, and Hannay is freshly knighted and living on a country estate with his wife and son. Still, he keeps his hand in as a “fixer” for the British authorities. So when Dominick Medina, a charismatic scholar but “utterly and consumedly wicked” mastermind, contrives to kidnap children from prominent families as part of a scheme to unleash economic chaos on an already weakened Europe, it’s Hannay who’s summoned to save the day. He has no clue where to start, save for a bit of baffling verse sent by the kidnappers. If there’s less derring-do here than in The Thirty-Nine Steps, it’s compensated for by eerie twists involving hypnotism, portrayals of London’s postwar decay, and a suspenseful showdown in the craggy Scottish Highlands.

The Dark Clouds Shining by David Downing (2018)

When we initially met him (in 2013’s Jack of Spies), Jack McColl was a peripatetic Scottish automobile salesman proficient in languages, who, in 1913, took on minor missions for Britain’s fledgling intelligence service. Eight years on, after eluding jeopardy in China, India, and revolution-era Russia—and becoming enamored of a clever, determined young American journalist, Caitlin Hanley—this now former espionage agent has finally been brought down, not by some enemy spy, but instead by a London judge committing him to prison for having belted an insolent constable. As the action picks up in The Dark Clouds Shining—the final entry in Downing’s McColl tetralogy—our hero is offered a deal by his ex-boss: a full pardon in exchange for McColl going to Moscow and figuring out why a perfidious “Irish-American firebrand” named Aidan Brady has been dispatched there on behalf of a rival UK security agency. Predictably, McColl’s assignment reunites him with Caitlin, who’s busy promoting women’s rights in Soviet Russia and has wed a sailor, Sergei Piatakov. Piatakov was a true believer in Lenin’s revolution, but by 1921, he’s lost faith that the ideals behind the czar’s overthrow can be realized. This makes him a perfect accomplice for Brady, as the pair set off for India—with McColl, Caitlin, and a Soviet secret policeman hot on their heels—to execute a plot meant to destroy that British colony’s hopes for independence. A sensational and satisfying finale to Downing’s series, rich with period detail and multidimensional characters.

Mark of the Lion by Suzanne Arruda (2006)

Bouncing across the muddy, dead-horse-littered front lines of northern France in the spring of 1918, American volunteer ambulance driver Jade del Cameron dreams of a future with David Worthy, the British ace pilot who’s asked her to marry him. That, though, is before she watches Worthy’s Sopwith Camel crash during combat, and before he expires in her arms, a final, desperate appeal on his lips: “Find my brother.” Jade dearly wants to honor his request, but everyone, including Worthy’s widowed mother, insists David was an only child. Unconvinced, and speculating that this misplaced sibling might have been born to a different woman while Worthy’s late father was away in British East Africa seeking his fortune, Jade secures a travel-writing assignment and heads for Nairobi. There, she’s welcomed into the occasionally cutthroat society of white colonials, demonstrates her mettle with a rifle (skills she’d learned while growing up on a New Mexico ranch), comes to appreciate the indigenous African culture, and—not incidentally—must defend herself against a putative witch. This laibon, as the natives call him, is said to exercise extraordinary power over animals, and to have terrorized local villages with a hyena—the same sort of cackling creature that killed Worthy’s father in his hotel room years ago. Now, it appears, he’s targeting his wrath on the comely, resourceful Jade as she sets off on her first safari. A feisty heroine, an exotic landscape, and a Hound of the Baskervilles air all enhance Arruda’s mystery-adventure plot.

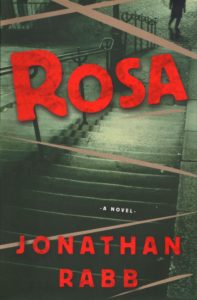

Rosa by Jonathan Rabb (2005)

In the immediate wake of the war’s end and Kaiser Wilhelm II’s abdication, Germany is riven by power struggles pitting radical communists against the new Weimar government. Amidst those troubles, a brooding old-school cop, Detective Inspector Nikolai Hoffner, is detailed—along with his more youthful and ambitious partner, Hans Fichte—to scrutinize the killings of middle-aged women in Berlin, all of whom have been found with cryptic carvings in their backs. These crimes suggest a serial marauder’s handiwork. Yet after the discovery of another dead woman, found in an abandoned subway station, Hoffner is shown one more corpse at the morgue—that of Rosa Luxemburg, a Polish Marxist linked to the recently crushed rebellion. Although she bears scars similar to the recent pattern, Hoffner isn’t convinced her demise belongs among the succession of “chisel murders.” His suspicions are further heightened by sudden interest in this case from the Polpo, Germany’s political police (“Hoffner had never figured out whether they had been created to combat or augment domestic espionage”). Might there be machinations afoot to lay off blame for Luxemburg’s homicide on a madman? Hoffner’s inquiries lead him to lace artists and Albert Einstein, and into the supple embrace of a teenage flower seller who also happens to be Fichte’s girlfriend. Rabb’s nimble blending of historical events into Rosa—the first of three Hoffner outings—lends depth to this noirish, evocative thriller.