When you think ‘Boston Noir,’ you probably think of The Departed or The Town or, David Ortiz help us, Boondock Saints. The best of Boston noir is a different shade of darkness than the more traditional film noir. (And that’s pretty damn dark.) Add on extra layers of guilt and a strong religious presence, and you’ve got something unique.

While filming in Massachusetts has become more prevalent in recent years, for decades there wasn’t much of film production in the state. All the films listed below were made in these darker days, when seeing the streets of Boston on screen was a rarer occurrence. These roots of film noir run deep and include some early examples of on-location shooting. Filmmakers shot in Boston because absolutely no other place would do, and that insistence made the city the main character. If you’ve finished up one of the more recently made Boston-based crime films and thought, “I need more of that,” here are a few suggestions for going deeper. (And a few suggestions of potholes worth avoiding.)

Robert B Parker’s Spenser (‘with an ‘S,’ like the poet,) is legend in these parts. A former cop who always is trying his best to walk the fine line of doing what’s right ethically, regardless of what the law says. He was always ably accompanied on the page by Hawk, his right-hand man, and his faithful dog, Pearl. Unfortunately, no one has been able to get the Spenser from the books completely correct on the screen. The 1980s TV show with Robert Urich came the closest, even though they moved Spenser’s apartment to the same firehouse that would eventually be inhabited by the kids from MTV’s The Real World. The subsequent TV movies, some starring Urich and some with Joe Mantegna are good, but they were all shot in Canada and, let’s be honest, Spenser without Boston is not Spenser. (At least they feature Spenser’s long-time girlfriend Susan Silverman, who, for reasons that continue to boggle the mind, was reduced to a one-season bit player in the TV show.) The less we think about Mark Wahlberg’s Spenser Confidential, the better. Pearl the wonder dog is not a beagle.

The books of Dennis Lehane are practically a genre in and of themselves, but the one adaptation worth focusing on is the first; Ben Affleck’s Gone Baby Gone. Yes, they shot it in real locations and not fully dressed sets and yes, a lot of locals were used as extras, but the film also contains something that seems to run deep in all of noir, but in Boston Noir it’s a particular vein: sins. We’re all guilty of something and it’s just a matter of time before we need to pay for our sins. The film is an excellent adaptation of Lehane’s Kenzie & Gennaro series and makes you long for more stories featuring the pair, either on screen or on the page. Mystic River and Shutter Island are both well made films by great directors and the less said about Live By Night the better. (The nicest thing you could say is that it’s heart is in the right place.) Stick with the original. Stick with Gone Baby Gone.

Night School from 1981 is a by-the-numbers slasher film, with murders being committed all around the city. It’s shot in the dark alleys of South Boston, with a motorcycle ride through Charlestown, weaving in and out of the shadows cast by the streetlights. As a slasher film, it doesn’t necessarily belong on this list, but I include it because of one murder that makes this film something special in the world of Boston-made entertainment. The murder is committed at the New England aquarium and the victim’s severed head is DROPPED IN THE MAIN TANK and slowly sinks to the bottom. As someone who visited the aquarium on numerous school visits, I never got to see anything half as cool as this, and, yes, I’ve seen the sea lion show.

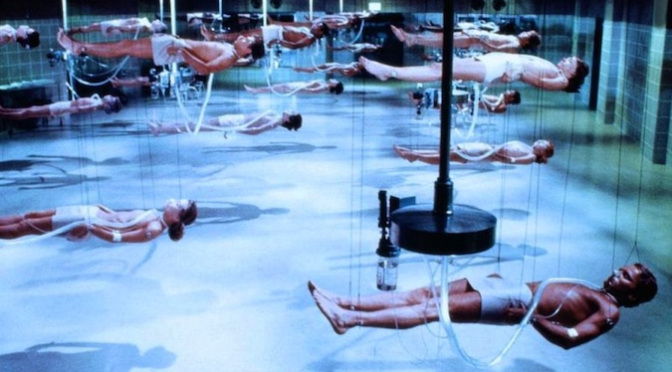

You usually don’t see Michael Crichton’s adaption of Robin Cook’s medical thriller Coma on these lists, but this needs to be remedied. Medicine-based crime is still crime. Set in the completely made up and, therefore non-litigious Boston Medical Hospital, a doctor played by Genevieve Bujold, this 1978 film is a great addition to the Boston noir list because it also includes a healthy handful of 1970s paranoia to the mix. The Jefferson Institute is actually an office building in Lexington and I hope one day to have a meeting there, if only to wander around to see if I can see bodies hanging by wires. For another Crichton-adjacent project, Dealing: Or the Berkeley-to-Boston Forty-Brick Lost-Bag Blues has a few nice shots of the city, but it’s not the main focus of the film. (And from looking at its IMDB page, you could be fooled into thinking a 1972 adaption of Crichton’s A Case of Need directed by Blake Edwards and starring James Coburn would be amazing, but sadly it is not. The Carey Treatment works better in theory than on screen.)

Fuzz is an interesting film on this list because it’s actually an adaptation of a novel in Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct series, which, are most definitely not set in Boston. The screenplay was written by Evan Hunter, who also wrote under the McBain penname. It’s the type of movie you could describe as a ‘romp,’ and a storyline that includes Burt Reynolds running around in a nun’s habit. But it also features some incredibly dark subplots, including one where someone is setting homeless people on fire. Even with that, the film does lighten up the genre, and include some great location shots which show the city as it was in 1972, including scenes set on Boston Common and in Copley Square which looks positively barren compared to today.

1950’s Mystery Street is an amazing noir film, directed by John Sturges (The Great Escape, Ice Station Zebra) and stars Ricardo Montalban (you know… Kahn) It has been said that this was the first studio film shot on location in Boston and also the first police procedural. It’s also good. Filmed at Harvard Medical School’s Legal Medicine Department, it tells the story of a girl murdered by her boyfriend who wants to cover up their relationship from his wife and kids. (The murder and the sinking of the car were shot on Cape Cod.) This film relies on the scientific side of detection more than most films but is still fascinating in spite of the fact that it’s not wall-to-wall car chases. AND it co-stars Elsa Lanchester, the Bride of Frankenstein herself.

Walk East on Beacon is a film which, in some versions has an exclamation point at the end of the title. This seems anti-climatic and a bit a of a disappointment since, if you followed those directions, you’d end up in Brookline. Made in 1952 and based on a Reader’s Digest article ‘written’ by J. Edgar Hoover, the film claims to be a true-life spy film, and, I guess it is, but now the anti-communist message comes on a little strong and overwhelms everything else. (The fact that one of the heroes in the movie is chemist Harry Gold, whose testimony in real life would be one of the main leads for the prosecution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg isn’t great either.) So why watch this? It’s early spy and Communist stuff with all the associated histrionics which can be enjoyable in the right frame of mind.

1991’s Lift is a great look at the life of a booster, better known to many as a shoplifter. Starring Kerry Washington in an early role, the film tells the story of Niecy, whose well-oiled system of stealing clothes and re-selling them is going great until, in an effort to re-build a relationship with her mother, she gets lured to pulling a much bigger job—a diamond heist. Nicey is walled in on all sides, unable to turn to anyone for help. It’s a bleak story, but an important addition to the genre. For a city with a well-documented and not great history with race, this film is a small step in the right direction. Also, being made in the 1990s, it captures in time the city when not a lot of other movies were, which is reason enough alone to check it out.

And I tell you all of that to tell you this: watch and/or read and/or re-read George V Higgins’ The Friends of Eddie Coyle. The legend of this movie has grown in each passing year and, truly, it deserves all the praise you can heap on it. Robert Mitchum is pitch perfect as a down-and-out Boston hoodlum, trying to do one right thing and, in classic noir tradition, just can’t seem to do it. The film also features a sequence shot in the old Boston Garden and a cameo by Bruins legend Bobby Orr. (This is the one and only time it is acceptable for anyone on any movie screen to yell, “Numbah fourah.”) Rife with guilt, faith, friendship and betrayal, it’s been great to see the appreciation of this film grow over the years. Higgins was an important writer in Boston-based crime, and crime writing in general. His dialogue was always superb and, like the best writers, he made it look easy. Even Boston crime legend Robert B Parker sang his praises. While his books never reached the heights of popularity of some of his followers, he is the foundation on which all the above is built.