It’s an adolescent rite of passage: wait until well after dark, then load up the car with a few friends (and maybe a six-pack or two) and go visit a local haunted spot. Frequently, the spot was the site of a horrific tragedy—or at least it was alleged to be. The term used by anthropologists and folklorists for this activity is “legend tripping,” and it happens all over the country.

Growing up in York, Pennsylvania, the premium haunted spot to visit was Rehmeyer’s Hollow. This was the site of a notorious witchcraft murder in 1928. Not only was the crime well-documented, it also led to a spectacular trial that attracted newspaper reporters from all over the world. As far as the teenagers of York County were concerned, Rehmeyer’s Hollow was the pinnacle of local fright sites.

I distinctly remember my first visit to Rehmeyer’s Hollow. It was a night in early spring, and I was with my buddy Dan in his tricked-out VW Bug. There was a legend that if you threw a rock or a stick at the Rehmeyer House, the house would throw it back. We intended to put that legend to the test. As we got deeper into Rehmeyer’s Hollow and closer to the house, I could feel the nervous excitement rising in the pit of my stomach. I knew intellectually that there was no such things as ghosts, but still . . .

I was contemplating this when Dan jerked in the driver’s seat and yelled, “What the hell is that?!”

“What?” I said. At first, I thought he was just messing with me, but he seemed genuinely startled.

“Up there in the trees!” He pointed out the windshield. Then I saw it, too: a light flashing through the still-naked tree branches overhead. A jolt of adrenaline hit my system, and I could feel all of my muscles tense.

“What the hell is it?” I asked.

“I think somebody’s just messing with us,” said Dan. “Probably just a couple of rednecks out jacklighting deer.”

Somehow, the thought of rednecks messing with our heads was almost as scary as ghosts. I think Dan was nearly as spooked as I was. When we got to the Rehmeyer House, there was no talk of throwing anything at it. We just did a slow drive-by, and then we were on our way back to town.

The Rehmeyer house and the area around it are still largely unchanged from when the murder happened almost a century ago. Part of the reason for this preservation is its remoteness; it just wasn’t easy to get to there. Even though Rehmeyer’s Hollow can be seen from Interstate 83, driving there involves navigating a lot of poorly-marked country roads through dense woodland, and it’s easy to get lost.

The trip must have been even more difficult back in 1928. On November 27 of that year, just before Thanksgiving, John Blymire and his companions John Curry and Wilbert Hess went to the house of Nelson Rehmeyer in Rehmeyer’s Hollow. Their goal was to retrieve Rehmeyer’s copy of a book called Long Lost Friend or a lock of his hair, then burn the book or bury the hair six feet under. The three men were convinced that Rehmeyer had put a hex on them and their families, and forcing him to surrender “the book or the lock” was the only way to lift the hex. They knew that Rehmeyer was a “witch,” because Blymire was also a witch, and that yet another witch had told Blymire that Nelson was the source of the hex that was causing them such misery.

For this abundance of witches to make sense, one needs to understand a little-known tradition that settlers of central Pennsylvania brought with them from the Palatinate region of Germany. The practice is called “powwowing,” or sometimes braucherei or hexerei.

Much about powwowing is benign. It is essentially folk medicine combined with faith healing. The “gift” of powwowing is inherited from a family member, and powwowers nominally use this gift to aid others in their community.

Much of the ritual involved with powwowing has Christian trappings. Powwowers frequently invoke the Trinity in their spells and incantations, and use accoutrements such as crucifixes and the Bible as part of their practices.

The Bible was also supplemented with other books. The most popular was called Powwows; or, Long Lost Friend. Written in 1820 by Johann Georg Hohman, this book was an indispensable powwowing tool. Not only was Long Lost Friend an amazing collection of information, the book itself was considered to be a source of power and protection for its owner. The book contains recipes and home remedies, prayers and spells. Most of these were benign, such as a recipe for beer, or a way to cure warts by rubbing them with roasted chicken feet.

Hexes and hexing are a large part powwowing, and the Pennsylvania German culture in general. Barns throughout German-settled area of Pennsylvania frequently sport colorful round decorations known as hex signs. These are intended to promote health for the crops and livestock, and keep away evil spirits.

Basically, a hex is an expressed wish that something bad happens to someone else. Most every powwower worth their salt would have to have some skill at removing hexes. Few, however, would admit to casting a hex, as doing so would be trafficking with Satan. And yet, in Pennsylvania in 1928, it seemed as though the hexes were flying fast and furious.

in Pennsylvania in 1928, it seemed as though the hexes were flying fast and furious.John Blymire’s grandfather and his father were known as powerful powwowers who were capable of effecting miraculous cures. His grandfather, Andrew, was especially esteemed for his abilities, and was said to have had a pet owl that could talk. As a child, John also showed a talent for powwowing—only natural for the progeny of a family of gifted powwowers.

John Blymire was raised on a farmstead in Hallam, a farming community east of the city of York. As a child, he was sickly and thin. He struggled in his efforts at school, when he managed to attend. At age 14, he dropped out of school and went to work in a cigar factory in York.

He seemed to have made a decent life for himself. In addition to making cigars, Blymire also powwowed for his friends and coworkers. It was not necessarily a lucrative avocation. Powwowers were supposed to accept only a “free will offering” in return for their ministrations, which often amounted to little more than thanks. Of course, many of the less-reputable powwowers made sure to let their customers know that there was a minimum price for “free will,” but Blymire was not one of these.

Blymire made a name for himself at the cigar factory one afternoon when he cured a rabid dog. As the day shift was leaving, someone cried “Mad dog!” A collie with foam dripping from its mouth rushed the crowd of workers at the front door. Blymire pushed his way to the front of the crowd, and stood between his co-workers and the collie, which was still howling and frothing at the mouth. He looked the dog in the eye and muttered the proper incantation from Long Lost Friend: “Dog, hold thy nose to the ground; God made both me and thee, hound.” He then made the sign of the cross over the collie’s head.

The results were immediate and amazing. According to eyewitness Amos King, “What happened next we couldn’t believe our eyes. This here big dog stops frothin’ at the mouth. Before we know it, John’s pattin’ his head and the dog’s lickin’ his hand. Then Blymire walks down the street and the dog follows, waggin’ his tail like he belonged to him. I tell you, the next day we all of us knew who John H. Blymire was.”

While Blymire’s stock as a powwower skyrocketed, it was not necessarily to his advantage. The cigar factory paid by piece work, and as Blymire spent more time tending to the needs of his coworkers, he had less time to roll cigars. His meager income suffered accordingly.

Blymire was also suffering in other aspects of his life. His health—never all that good to begin with—began to decline. He lost weight, and his clothes began to hang off of his already-skinny frame. There were dark circles under his eyes from the constant headaches and lack of sleep. As these problems worsened, Blymire became convinced that he was the victim of a hex.

His father and grandfather were unable to help him, so John Blymire began a years-long quest to determine the identity of his tormenter and lift the hex. He patronized powwowers near and far in an attempt to find out who had hexed him. This endeavor consumed what little money he had and most of his free time. He sometimes hitchhiked 80 miles to visit a powwower whom he thought could help him. None could, and his health continued to suffer.

For the next eight years, John Blymire continued his lonely existence, moving from boarding house to boarding house and job to job. What little cash he was able to acquire was promptly handed over to any powwower who claimed they could identify the source of Blymire’s hex. It was a lonely life—until he met John Curry.

Curry had had a difficult upbringing. His father died when he was six, and his mother remarried to an alcoholic lout named Maclean. Maclean was almost always at home, drunk, and abusive, and he made his stepson’s life miserable. At age thirteen, Curry’s large farm-boy frame allowed him to finagle his way into the Army. However, his true age was soon exposed, and he was discharged. In the summer of 1928, he returned to York and found work in a cigar factory.

Curry sat next to Blymire at work, and the two soon struck up a friendship despite the disparity in age (Curry was thirteen; Blymire was thirty-two). Each found the relationship beneficial. Curry had found the father-figure he craved, and Blymire had someone who listened to and respected him.

Around that time, Blymire finally got the answer for which he had been looking for so long. He engaged the services of a woman named Nellie Noll, who was known as the “River Witch of Marietta.” Noll was known to be one of the most powerful powwowers in central Pennsylvania.

Noll lived up to her reputation, and was able to come through where all of the other powwowers had failed. After a number of five-dollar consultation sessions, the River Witch gave Blymire the name of the person who had hexed him: Nelson Rehmeyer.

Blymire was surprised. He had known Rehmeyer his entire life. In fact, Nelson Rehmeyer had powwowed for Blymire when he was five years old, effecting a cure when his father and grandfather could not. Blymire had also worked at Rehmeyer’s farm when he was ten, picking potatoes for twenty-five cents a day.

Blymire was initially skeptical of Nellie Noll’s revelation. She told him that she could prove it, and asked Blymire to take a dollar from his pocket and hold it face down in his left hand. She then instructed him to hold it face up in his right hand, and look at the picture. Blymire was astonished to see the face of Nelson Rehmeyer looking up at him.

He was convinced, and asked the River Witch what he could do to lift Rehmeyer’s hex. She told him that he could either retrieve Rehmeyer’s copy of Long Lost Friend and burn it, or obtain a lock of Rehmeyer’s hair and bury it six feet under.

The problem then became one of transportation. Rehmeyer’s Hollow was difficult to reach from York, and neither Blymire or his protégé Curry had access to a vehicle. Fortunately, Blymire had recently made the acquaintance of a young man who was both sympathetic to his plight, and could get an automobile.

Wilbert Hess was seventeen when he met John Blymire. Hess had been raised on a once-prosperous farm outside of York. Around the middle of 1926, things began to go wrong on the Hess farm: the crops failed, the chickens quit laying and the cows ceased giving milk. The Hess family immediately knew what the problem was: they had been hexed. Like Blymire, they struggled in vain to identify the source. By the middle of 1928, Wilbert’s father, Milton, had been forced to sell of most of his land. To make ends meet, father and son went to work driving trucks for the Pennsylvania Tool Company in downtown York.

The garage of the company was located directly across the alley from the rooming house where John Blymire lived. Blymire and Wilbert Hess struck up a relationship. Before long, young Hess had confided in Blymire about his family’s troubles. Ever generous, Blymire offered to apply his powwowing talents to identify the Hess family’s nemesis. Unfortunately, his skills were not up to the task.

He paid another five-dollar visit to the River Witch, who revealed that the identity of the Hess malefactor was, by astounding coincidence, also Nelson Rehmeyer. The Hesses were surprised; they had never even heard of Rehmeyer. However, when informed that this was the pronouncement of the venerable River Witch of Marietta, they accepted it as gospel. All that remained now was to confront Rehmeyer and obtain the book or the lock.

This would be no mean feat. Rehmeyer was considered a potent powwower in his own right. He was also somewhat of an eccentric, and his odd behavior had caused his wife to leave him, taking their two daughters to live on her parents’ farm several miles away. He was a physically imposing man, powerfully built and well over six feet tall. Nelson Rehmeyer was not going to be an easy man to overcome.

As far as John Blymire was concerned, he did not have any other options. On the night of November 27, Blymire, Curry and Hess climbed into a car owned by Hess’s brother, Clayton. Clayton dropped them off about a mile away from Rehmeyer’s house. The three hiked through the thick woods in the late November darkness.

They arrived at Nelson Rehmeyer’s house shortly before midnight and pounded on the door. Rehmeyer was probably not surprised to see them; Blymire and Curry had actually visited him the night before, but had gotten cold feet and left without confrontation. Perhaps they wanted to wait until they had the husky Wilbert Hess with them to tip the scales.

Rehmeyer admitted the three into his house. Tonight, there was going to be no beating around the bush—Blymire immediately demanded that Rehmeyer surrender “the book.” Rehmeyer apparently decided to play dumb. “What book?” he replied. Blymire was having none of it. With a cry he jumped on Rehmeyer, and Curry and Hess helped hold him down.

The big man struggled mightily. Curry had brought along a number of lengths of pre-cut rope to tie up Rehmeyer. They attempted to restrain him, but Rehmeyer—perhaps realizing that he was in more danger than originally anticipated—put up a ferocious fight.

Blymire took one of the lengths of rope and cinched it around Rehmeyer’s neck. Even with a constricted airway, Rehmeyer continued to fight back against his attackers. John Curry ran outside to the woodpile and returned with a chunk of wood. With this, he battered the struggling Rehmeyer, pounding the length of wood on his head and face repeatedly, as Blymire and Hess continued to strangle and kick the struggling powwower.

At last, Rehmeyer succumbed to the assault. His battered, bloody body, face almost unrecognizable, was motionless on the floor of his parlor. John Blymire looked on his handiwork and cried, “Thank God! The witch is dead!”

Blymire and his accomplices had given practically no thought as to what was to happen afterwards. With Rehmeyer dead, there was no longer any reason to retrieve the book or the lock—the hex died with the witch who cast it. A quick search of the house turned up a small tin box full of pennies, which they split. In a half-hearted attempt to conceal the crime, they sloshed a couple of dippers of water on the floor to wash away fingerprints. They also propped couch cushions on top of Rehmeyer’s corpse, doused them with lantern oil, and set them alight.

Then they just went home.

It was two days before Rehmeyer’s remains were discovered. (The attempt at arson failed; the cushions had burned briefly and then went out.) On the morning of November 30, a nearby farmer named Oscar Glatfelter heard the anguished braying of Rehmeyer’s unfed mule and went to investigate. He discovered Rehmeyer’s battered and singed body and alerted the authorities.

Blymire, Curry and Hess were apprehended so quickly that the news of their arrest was in the same edition of the paper as the news of Rehmeyer’s murder. Blymire had made no secret of his intention to confront Rehmeyer, and had actually stopped at Mrs. Rehmeyer’s house the night before the murder to ask about his whereabouts. All three were in custody by sundown. The men readily confessed to the murder during interrogation sessions that lasted all night. Blymire seemed more relieved at having the hex lifted than he was concerned about legal repercussions.

News of the murder—and especially its motive—quickly began to spread. Out-of-state newspapers began to sensationalize the story of the modern-day “witchcraft murder” in rural Pennsylvania. To the consternation of the civic and business leaders of York County, reporters and photographers poured into York and began filing unflattering stories about the backwards beliefs of the “dumb Dutchmen” of the area.

The press worldwide seemed appalled that in those modern times American citizens could still believe in such medieval notions as witchcraft, and even be willing to commit murder for these beliefs.The late 1920’s was regarded as a technological miracle age, with electricity, telephones, radio and powered flight becoming widespread. The press worldwide seemed appalled that in those modern times American citizens could still believe in such medieval notions as witchcraft, and even be willing to commit murder for these beliefs. New York World columnist William Bothio was particularly aghast that “. . . only an hour as the motor runs from Philadelphia . . . genuine witches are killing each other at midnight with incantations ‘round infernal fires.”

This sort of coverage was not uncommon, but it was entirely unwelcome. In York, the citizens wanted to get the legal process over with quickly so the “furrin press” would go back home and stop painting the locals as superstitious hicks. This communal desire for speedy resolution had an adverse effect on the trials of John Blymire, John Curry, and Wilbert Hess.

Blymire’s case went to trial first. As a pauper, he was assigned an inexperienced public defender named Herbert Cohen. The lawyer’s job was made much more difficult by the District Attorney, Amos Herrmann, and the judge, Roy Sherwood. Herrmann and Sherwood represented the Old Guard of York, and did not want any further besmirchment of the town in the worldwide press.

To that end, Herrmann and Sherwood labored to preclude any mention of witchcraft or powwowing during the trial. The confessions that were submitted to the court were severely bowdlerized—statements that had been freely given over the course of eight hours were reduced to a few paragraphs. There was no mention of powwowing, or Blymire’s long search for the witch he believed had hexed him. As far as the state was concerned, the motive for the murder was the small box of pennies the three had taken from Rehmeyer’s house; nothing else would even be considered.

It soon became evident that the only thing in question in the trial was whether or not John Blymire would be sent to the electric chair. There was not a long wait to find out. At the end of the third day of the trial, the jury deliberated less than two hours before returning their verdict: guilty of murder in the first degree, with a life sentence. Cohen was furious, but his client was surprisingly sanguine. When asked about the prospect of spending the rest of his life behind bars, Blymire said, “I am happy now. I am not bewitched anymore. I can sleep and I am not pining away.”

John Curry was the next to be tried, and the proceedings went even more quickly. The defense rested on the afternoon of the first day of the trial. When the jury returned the next morning, they again required less than two hours to reach a verdict. Once again, it was guilty of murder in the first degree, with life sentence.

As the stunned John Curry was being led away from the courtroom, jury selection was underway for the trial of Wilbert Hess. Unlike the other two defendants, Hess was represented by a hired lawyer. The Hess family had pooled its resources to hire Harvey Gross, an eminent York County criminal defense attorney. Short, squat and pugnacious, Gross was known as the Bulldog.

Gross didn’t have any more material to work with than did Blymire and Curry’s attorneys, but he knew how to work a jury. First, he had Wilbert Hess go through his highly expurgated confession line by line, asking particulars about the various statements. He was quickly able to demonstrate to the jury that the written confession was full of errors and contradictions. The approach greatly reduced the impact of the damning confession.

Next, Gross introduced a parade of character witnesses, all willing to testify to the good character of Wilbert Hess. Several dozen had appeared as requested, but the Bulldog didn’t need to get testimony from them all—just showing the jury the number of fellow citizens willing to vouch for Hess’s good character was enough.

Finally, the Bulldog conducted an 80-minute closing statement that had the panel spellbound. He urged the members of the jury not to sacrifice justice in order to spare the reputation of the town: “Yet, in truth, York does not have to be vindicated. It does not have to draw the last drop of blood from the heart of a boy to save a good name that has stood for generations.” The jurors and observers in the courtroom ate it up. The jury deliberated for a little over two hours before returning a verdict of murder in the second degree. Bulldog Gross chalked this up as a win, and shook each juror’s hand as they left the box.

Judge Sherwood passed sentence on all three men shortly thereafter. Blymire and Curry were sentenced to life imprisonment; Hess received ten to twenty years. The entire process from gavel to gavel had lasted a mere nine days.

The national press was critical of the sentences, particular that of John Curry. Renowned columnist Will Rogers wrote, “. . . a Pennsylvania jury sentenced that fourteen-year-old boy to life imprisonment because he believed in witchcraft. That’s all he’d ever been raised up to. It’s like sentencing one of our children for acting according to their religious beliefs. No doubt about there being witches in that county—the jury’s verdict shows that plainer than the boy’s deed.”

It’s certain that the York establishment was not pleased with Rogers’ remarks and others like them. Eventually, the uproar surrounding the witchcraft trial abated and the “furrin press” went home, which was to everyone’s satisfaction.

Installed in Eastern State Penitentiary near Philadelphia, Blymire, Curry, and Hess became model prisoners. Curry and Hess were paroled after ten years. They went back to York County and became successful and respected members of their communities. Curry developed into a well-regarded painter, who was much sought out for his portraits.

John Blymire spent much more time in prison than his accomplices. Initial attempts at leniency were opposed by members of the Rehmeyer family, who did not feel safe about Blymire returning to the community. In early 1953, Governor John S. Fine commuted Blymire’s sentence, after he had served 24 years. Blymire stayed in the Philadelphia area, where he worked as a janitor in an apartment building. His subsequent visits to family in York County were understandably infrequent.

Today, Rehmeyer’s Hollow stands much as it did when Nelson Rehmeyer was murdered nearly a century ago. Most of the densely-wooded land is now part of Spring Valley County Park. Nelson Rehmeyer’s house still stands, largely unchanged from when it was built. It is still owned by the Rehmeyer family, and is occasionally occupied. From time to time, the house is made available for tours to the public.

There may be still be powwowers in the area as well, although they were thin on the ground when I lived there thirty-five years ago, and are probably even more scarce now. One thing’s for certain: kids from all over the area still travel down to the Witch House in Rehmeyer’s Hollow to see the site of the brutal witchcraft murder of Nelson Rehmeyer. It’s quite a legend trip.

***

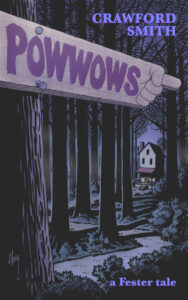

My latest novella, Powwows, is based on the story of the Rehmeyer murder. Deep in the woods lives a wizard called the Professor. In the depths of the Depression, the residents of Fester, Pennsylvania call on “powwowers” such as the Professor to heal ailments, tell fortunes . . . and exact revenge. When an upstart powwower threatens to horn in on the Professor’s business, he starts making plans for his own revenge. The sinister forces he sets in motion spiral out of control, and soon threaten to consume the leading citizens of the town.