“It would be so easy to stay…Could one fall in love with a whole country—just like that?”

If the country is Alexander McCall Smith’s Botswana, then yes. The speaker is Clovis Andersen, a private detective (though admittedly, not a very good one) from Muncie, Indiana, and the author of The Principles of Private Detection. He has just recently had the chance to meet the mainstays of the No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency in Gaborone—its founder, the “traditionally-built” Precious Ramotswe, and her assistant, the bespectacled Grace Makutsi—and he has been swept away by the warmth, humor, intelligence, and big-hearted blend of traditional and modern values that define not only these two women, but the entire nation.

If you’ve read even one of the twenty-one books published between 1998 and 2020 that chronicle the professional and domestic adventures of the agency, plus its friends, associates, and families, then you know what he’s talking about.

The core of the books lie not in the cases they solve, but in the way they go about it; the interactions both with the people and the land; the wry observations and commentaries; and the deep, sometimes dark, human truths that are revealed along the way. These aren’t major crimes, usually, at least not in the way we’re accustomed to thinking about them. No one gets murdered. “We aren’t here to solve crimes,” Mma Ramotswe says in Morality for Beautiful Girls (2001). “We help people with the problems in their lives.”

That doesn’t mean that the deep seriousness of those problems can be underestimated. “Even the most inconsequential of secrets could weigh heavily on a person’s soul,” she notes in The Woman Who Walked in Sunshine (2015). “An act of selfishness, some small unkindness, could seem every bit as grave as a dreadful crime; an entirely human failing, a weakness in the face of temptation, could be as burdensome as a major character flaw: the size of the secret said nothing about its weight on the soul.”

Although normally cheerful, Mma Ramotswe herself knows a good deal about human failings. The headstrong daughter of a revered cattleman, the young Precious fell hard for a handsome jazz trumpeter who ended up beating her so badly, she lost a baby, a mental scar she never lost but was at least able to exorcise partly in the dramatic showdown that marks In the Company of Cheerful Ladies (2004) (see “Essentials” below). The trauma drove her back to her father’s house, however, where for the next fourteen years, she kept house for him until his passing shortly before her thirty-fourth birthday.

On his final day, he takes her hand and tells her to sell the cattle and buy a business: “A butchery, maybe. A bottle store.” Yes, she says, I will: “I’m going to set up a detective agency.” His eyes widen, he says, “But…but…” and then he dies.

He isn’t the only skeptic. Her father’s lawyer doubts the whole process – “Can women be detectives?”—a comment that naturally irritates her, especially since his zipper is half undone, but she only replies quietly, “Women are the ones who know what’s going on. They are the ones with eyes,” and leaves, money in hand (The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, 1998).

Eyes she certainly has, plus a deep well of common sense, a natural gregariousness and curiosity, an acute lie detector, and an understanding of psychology—“that is what they called it these days, but in her view, it was something much older than that. It was woman’s knowledge” (The Full Cupboard of Life, 2003). She applies all this through some simple techniques:

“Private detection is all about soaking things up. You speak to people. You walk around with your eyes open. You get a feel for what’s happening. And then you draw your conclusions” (Blue Shoes and Happiness, 2006).

“When I want to find something out, I usually ask somebody directly. People love to talk, especially in Botswana” (The Miracle at Speedy Motors, 2008).

“If you listen hard enough, people will give themselves away. They will always mention the things that are preying on their mind, the things that they have done wrong. All you have to do is listen: it always comes out” (The Limpopo Academy of Private Detection (2012).

Of course, sometimes you have to help that process along a little bit. Take the woman in The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency who has had a man living in her house for three months, claiming to be her long-lost Daddy. Precious borrows a nurse’s uniform, roars up to the house in her little white van, tells him he must come quickly because his daughter has been in a very bad accident, and will need him to donate blood—a lot of blood. So much, in fact, that, well, he might die. The man pales, confesses that actually… and she gives him five minutes to get out.

Then there is the man who wants to atone for a misdeed committed twenty years before, but he needs to know where to find the family—and an officious government clerk won’t give Mma Ramotswe the address: It’s against the rules!

“But that is not the rule,” said Mma Ramotswe. “I would never tell you your job—a clever man like you does not need to be told by a woman how to do his job—but I think that you have got the rule wrong. The rule says that you must not give the name of a pensioner. It says nothing about the address. That you can tell.”

The clerk shook his head. “I do not think you can be right, Mma. I am the one who knows the rules. You are the public.”

“Yes, Rra. I am sure that you are very good when it comes to rules. I am sure that this is the case. But sometimes, when one has to know so many rules, one can get them mixed up. You are thinking of rule 25. This rule is really 24(b), subsection (i). That is the rule that you are thinking of. That is the rule which says that no names of pensioners must be revealed, but which does not say anything about addresses. The rule which deal with addresses is rule 18, which has now been cancelled. Have you not read the Government Gazette?…Of course, if you are too junior to deal with these matters, then I would be very happy to deal with a more senior person.”

She is making it all up, of course, but the clerk is not about to admit that he has no idea what she is talking about, nor that he is lacking in authority: “I am quite senior enough. And what you say about the rules is quite correct. I was just waiting to see if you knew. If only more members of the public knew about these rules, then our job would be easier” (The Kalahari Typing School for Men, 2002).

Address in hand, she helps her client along his way—though there will be twists to come before the case is concluded.

Mma Ramotswe mixes all these investigative and histrionic talents with a keen sense of traditional manners, because she knows her people – the proper way to greet a countryman; to inquire after his health and night’s sleep; to offer water in a very dry country; to engage sideways, without staring in a direct or challenging way; and especially to establish “the old bonds that had always held the country together; a subtle, usually unspoken sense of mutual interest and respect that people could forget about, but that was still there and could be invoked by those who held with the old ways. I am your sister. There was no simpler or more effective way of expressing a whole philosophy of life (Tea Time for the Traditionally Built, 2009). There is an expression in the original Setswana that goes Motho ke motho ka batho, loosely translated, “A person is a person because of other people.”

Mma Ramotswe believes in the old ways, but also believes that some change is necessary. “I am a modern lady and have no desire to go backwards rather than forwards. It all depended, she felt, on where you thought forwards was” (To the Land of Long Lost Friends, 2019).

On the one hand, “People had more of a chance in life no matter where they came from; those who worked for other people had more rights, were protected against the cruelty that employers could show in the past. And the hospitals were better, and school bullies found it harder to bully people” (Precious and Grace, 2016).

On the other hand, “Botswana had been a special country, and still was, but it had been more special in the days when everybody—or almost everybody—observed the old Botswana ways. The modern world was selfish, and full of cold and rude people….We do not talk about wise men or wise ladies any more; their place had been taken, it seemed, by all sorts of shallow people—actors and the like….It was worse, she thought, in other countries, but it was beginning to happen in Botswana and she did not like it” (Full Cupboard, 2003).

To sum it up: “You had to look after other people because if you did not, then the world was a cold and lonely place, a place where, if you stumbled, there would be no hand to pull you to your feet” (How to Raise an Elephant, 2020).

Her assistant, Grace Makutsi, who rises steadily through the ranks during the series from secretary to assistant to associate detective to partner to (in her head, anyway) co-managing director, feels much the same way, because for too long she felt lost in that cold and lonely place. She has seen one brother die from AIDS. She comes from a small rural village in northern Botswana, one of seven children crammed into two rooms, “daughter of a man whose cattle had always been thin” (Kalahari). She is thin herself, with “difficult” skin and glasses that are too large and round for her face, and she is well-aware of the fact that she is “a dark girl in a world where light-colored girls with heavily applied red lipstick had everything at their disposal” (Tears of the Giraffe, 2000).

She is a striver. Her ticket to a better world is the Botswana Secretarial College, where she earned an unprecedented 97% on her final examination, a fact that she will bring up at the drop of a hat. Her steady advancement at the agency is due to her becoming a strong detective in her own right (with the guidance of Precious Ramotswe and Clovis Andersen’s The Principles of Private Detection), but she always retains a defensiveness born of her background, a prickliness that can burst out at inopportune moments, a genuine anger at those who do not measure up, especially men. When going to see one man who has misbehaved, she declares to Mma Ramotswe, “I shall be speaking on behalf of all the women in Botswana who have been let down by men. On behalf of girls whose boyfriends have pretended that babies have nothing to do with them. On behalf of women whose men go off to bars all the time and leave them at home with the children. On behalf of women whose husbands see other women. On behalf of women whose husbands lie and steal their money and eat all the food and….” (The Saturday Big Tent Wedding Party, 2011).

Her ambitions also lead her to tackle other projects of varying success—a typing school for men! A fashionable restaurant (“I do not want any riff raff coming in and eating there”)!—and to butt up against Mma Ramotswe from time to time, but the detective agency is always at the core of her self-image. So is another passion: shoes. She never had any as a girl, and they have become her greatest objects of desire. She can not pass a store without falling in love with a new pair, even if she cannot afford them. So strong is her attachment that they actually speak to her, and they can be quite snarky—“You’re on your own, Boss!,” they might say (at least they call her “Boss”); “Don’t look at us, Boss. It was your big idea, not ours”—but they can also be quite helpful, warning her, for instance, of a snake under her bed or, in the case of that fancy restaurant of hers, that something is badly wrong in the kitchen: “That sauce is made of lies.”

No matter how many pairs of shoes she owns, though, that cold and lonely place remains within her, until the day she meets a man at a dancing class. He is plain, awkward, has a bad stutter, and is clearly no catch—but she falls for him. He is good and kind and thinks she’s beautiful, and that furniture store he works in—it turns out he owns it. Money is no longer a problem. Love is no longer a problem. And when her baby is born, her life is complete.

Except for one thing. Grace has a nemesis. She appears fleetingly in the sixth book, In the Company of Cheerful Ladies, but she is so wonderfully awful, McCall Smith keeps bringing her back, raising her to new heights of perfidy as she makes the lives of Precious and Grace hellish. One of the fun-loving, empty-headed, glamorous girls who dominated the social scene at the Botswana Secretarial College, Violet Sephotho is constantly scheming and all too often gets away with it. She worms into the affections and business affairs of Grace’s fiancé in Tea Time, sends poison-pen letters in Miracle, tricks a man out of his new house in The Double Comfort Safari Club (2010), sabotage Grace’s restaurant in The Handsome Man’s De Luxe Café (2014), sets up her own scam secretarial college in Sunshine, gets nominated for a Woman of the Year award in Precious and Grace, and is the deciding factor that forces a highly reluctant Mma Ramotswe to run for the Gaborone City Council in The Colours of All the Cattle (2018), to keep Violet—who had already run once for the Botswana Parliament—out of office. Violet is unprincipled and shameless—“full of nothing,” Grace tells her. “You are full of nothing. There is nothing in your head and nothing inside that heart of yours. Nothing” (Sunshine)—and we love every page she’s on.

Precious, Grace, and Violet aren’t the only memorable characters. McCall Smith builds a whole company of them, whom we love to follow. There is Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni, Precious’s adoring husband, a plain, honorable man, often bemused by her activities, and devoted to his work as an automobile mechanic at the garage he owns, Tlokweng Road Speedy Motors. Cars have souls, he knows; if you just listened to them, they would tell you what’s wrong. In How to Raise an Elephant, a customer expounds in detail as to why he prefers Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni’s work to that of any of the other local mechanics: “They are computer operators, that’s what they are. They call themselves mechanics, but I may as well call myself a brain surgeon…They plug your car into their computer—‘One thousand pula, please, payable now’—and the computer says there is big rubbish going on somewhere, and it tells them where it is. But do you think they know how to fix that rubbish? They do not….What the computer says is, ‘You must take out that part and replace it with a new part, number 678 a/b (three thousand pula)….You are a proper mechanic, rather than an IT person—you have tools. You have oil cans. You know how an engine works.”

Mr. J. L. B. Matekoni’s life is complicated, however, by his two apprentices, Charlie and Fanwell. They are lazy and ham-handed and all they seem to think about is girls. “There is something missing in their brains,” he complains to Precious in Full Cupboard. “Sometimes I think it is a large part, as big as a carburetor, maybe.” That is all we really know about them for quite some time—Fanwell doesn’t even have a name until the tenth book in the series—but gradually McCall Smith colors them in. Fanwell doesn’t pass his apprentice exams for a long time because he is dyslexic; he hasn’t furthered himself because all of his pay goes to support a grandmother, aunt, and four young ones with whom he lives. Charlie never passes the exams at all, because he’s (sigh) Charlie: feckless, carefree, his head full of plans that never happen. Nevertheless, Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni harbors a rough affection towards the two of them, and even Grace Makutsi, who is also the assistant manager of the garage (the detective agency is housed in a room with a separate entrance) has a weak spot or two for them, when she isn’t dressing them down. In the end, when Fanwell is in some very bad trouble in The Limpopo Academy of Private Detection (see “Essentials” below), it is Charlie who comes to the rescue, and, for all his many amorous misadventures, it is Charlie who falls completely and honorably in love, and despite all the odds, marries the woman of his dreams (seriously, he is definitely punching above his weight here).

Enter for a chance to win a collection of Alexander McCall Smith mysteries.

Enter for a chance to win a collection of Alexander McCall Smith mysteries.

Other character mentions must include Mr. Phuti Radiphuti, the estimable husband of Grace Makutsi; the slight, earnest Mr. Polopetsi —“If a powerful gust of wind should come sweeping in from the Kalahari, he could easily be lifted up and blown away (Blue Shoes)—an ex-con wrongly convicted for a crime he didn’t do, who fills in occasionally as a part-time detective, where his Bushman tracking skills come in handy; Mma Potokwane, the very formidable matron of the local orphan farm, who, for the orphans, can coax money, favors, and decisions out of anybody and make them think it was their own idea (“I wouldn’t want to be the lion who tried to eat her,” muses Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni in The Handsome Man’s De Luxe Café); and, last but certainly not least, the two children from the orphan farm that Mma Potokwane prevails Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni to take home with him without discussing it with Precious Ramotswe first: a twelve-year-old girl in a wheelchair named Motholeli and her four-year-old brother Puso. Three years ago, their Masarwa (Bushman) mother died, and “when a Masarwa woman died and she’s still feeding a baby, they bury the baby too. There just isn’t the food to support a baby without a mother. That’s the way it is” (Tears of the Giraffe, 2000). The girl hid in the brush, and when her brother was buried in shallow sand, she crept out, uncovered him, and ran away with him as fast as she could.

Who could say no to that story? Certainly not Mr J.L.B. Matekoni—or Precious Ramotswe. Certainly not the reader.

Together, the members of the ensemble, each in his or her own way, get to tackle a wide variety of cases (even Charlie gets to assist on a few of them, and—once and only once—Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni: “The rays of the sinking sun had caught the window…and were flashing signals. Red. Stop, Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni. Stop. Go back to what you understand,” The Good Husband of Zebra Drive, 2007). They track wayward husbands, wives, and daughters; uncover frauds; investigate politicians and financiers; check out suitors and beauty queens; tread carefully around claims of witchcraft. Who is the Indian woman with no name or memory? Why does the Canadian woman want to find the caregiver she last saw when she was eight years old? What is the explanation for three hospital deaths in the same bed at the same time during the last six months? Is the young man claiming to be a late farmer’s nephew for real, or an impersonator? Could the brother of an important government man have been poisoned by his new wife?

All of this takes place in that grave, beautiful place called Botswana, a country of empty spaces and echoing skies, of vast dry deserts and great purple rain clouds:

“The sun came up, at first a curved slice of golden red, and then a shimmering, glowing ball, lifting itself free of the line of tree-tops, light, effortless, floating. And then the sky opened up, freed of its veils of darkness, a great pale blue bowl above…above me, thought Mma Ramotswe—and all the other people who were getting up now in Botswana; above people for whom this was their first day on this earth—the tiny, fragile babies—and above those for whom it was their last—the aged people who had seen so much and who knew that the world was slipping between their fingers …all—or most of us, at least—trying our best, trying to make something of life, hoping to get through the day without feeling too unhappy, or uncomfortable, or hungry—which was what just about everybody hoped for, whether they were big and important, or small and insignificant. She sighed. If only people could keep that in their minds—if they could remember that the people they met during the day had all the same hopes and fears that they had, then there would be so much less conflict and disagreement in the world. If only people remembered that” (The Colours of All the Cattle).

At the end of the day, she reflects, she knows one thing for sure: “She was a good detective and a good woman. A good woman in a good country, one might say. She loved her country, Botswana, which is a place of peace, and she loved Africa, for all its trials. I am not afraid to be called an African patriot, said Mma Ramotswe. I love all the people whom God made, but I especially know how to love the people who live in this place. They are my people, my brothers and sisters. It is my duty to help them to solve the mysteries in their lives. That is what I am called to do” (The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency).

***

Who is Alexander McCall Smith, and why is he so in love with Africa? Because he was born and raised there.

His father was a public prosecutor in Bulawayo in southern Rhodesia, now known as Zimbabwe; his grandfather was a doctor; and his mother spent a good amount of time writing an unpublished novel set in the Belgian Congo. Put them all together, and you get the man who became not only a celebrated author but a renowned law professor and specialist in medical ethics.

When he was just seventeen, he left Africa to study law at the University of Edinburgh, where he earned an LLB and Ph.D. before teaching at Queen’s University in Belfast for a time. But Africa still called him, and in 1981, he returned to a temporary teaching job in Swaziland, and then moved to the University of Botswana, where he not only helped found the law department, but co-wrote the country’s criminal code, later published as The Criminal Law of Botswana. So he knows what he’s talking about. Even though he returned to Scotland in 1984 to become Professor of Medical Law at the University of Edinburgh, to this day, he says, he visits Botswana every year to see friends and soak up the country—“the people are so nice—it’s a very spiritual part of the world, very intensely beautiful”—and occasionally go through the law reports at the Botswana High Court, looking for real cases of interest.

His first story was written when he was eight. “It was called ‘He’s Gone,’ but where he went, or why he went, I really can’t recall.” It was all of one page long, handwritten. He sent it off to a publisher, “and the publisher wrote back – it was an amazing thing. Unfortunately, they said they couldn’t do this one, but in the future, they might be able to.”

It was while he was teaching in Belfast that he decided to enter a literary competition which offered two prizes, one for a children’s book, one for an adult novel. He submitted a children’s book—and won—starting a career that has produced about forty children’s books so far. Then, on one of his trips to Botswana, he and a friend’s wife went to collect a chicken for dinner, and bought it from a cheerful woman in a red dress who chased it down for them, snapped its neck, and presented it with a flourish. “It was a tiny place with a beautifully kept yard. She had great style and panache and a wonderful smile. I just remember thinking, ‘What is this woman’s story? There is a story there, in this apparently very straightforward life.’”

He did nothing about it for a long time, but finally in the late 1990s, started writing about her. He took the manuscript to Edinburgh’s Canongate Books, which had recently published a collection of his short stories—and got turned down. Finally, a small publisher called Polygon took it and put out a whopping 1,500 copies. “I remember when they got through them,” he says, “they came to me and said, ‘Well, we may even consider a reprint, we may do another five hundred.’ And I thought, ‘Steady on, you don’t want to overdo the thing.’ It wasn’t very lucrative at all, but I was reconciled at that time: ‘OK, this is where I sit.’ I was perfectly happy with that.”

That situation remained for the next two books, and they weren’t lighting any fires in the U.S., either, where the first three books were available through Columbia University Press/Polygon. Then in January 2002, the New York Times ran a full-page review of all three books, titled “The Miss Marple of Botswana,” and publisher attention exploded.

“I remember the precise moment when my life changed,” he says. “The books had been acquired by Random House in New York [Pantheon for hardcover, Anchor Books for paperback], and I went over in a fairly modest way to meet my new editor. I thought that I’d have about half an hour and be shown the door. But I got this wonderful welcome, they hired a whole restaurant for lunch with all sorts of people. I arrived at eleven a.m. and went out into the street at four p.m., and thought, ‘Oh, heavens, this life is different now.’”

It was true on his own side of the Atlantic, as well. Though the books had been readily available in Scotland, England had not paid much attention. It was only when they skyrocketed in America that the word filtered back, and they became huge throughout the U.K.

At this time, he was not only the Professor of Medical Law at the University of Edinburgh, but the chairman of the ethics committee of the British Medical Journal, the former vice-chairman of the Human Genetics Commission of the United Kingdom, and a former member of the UNESCO’s International Bioethics Committee. He had to give it all up. He tried just taking a temporary leave of absence, but the demand became too great—and he found, to his delight, that the opportunities for all kinds of other fiction, in all kinds of other formats, came flooding in as well (see the Book Bonuses, below).

Now, he alternates among all of them, at a pace of about 1,000 words an hour in two- or three-hour bursts. He writes, he says, in “a dissociated state,” sitting down at the keyboard and letting it flow, “and it all just comes very quickly and ready-formed.”

And when he’s not writing books? He helped to found an opera house in Botswana outside Gaborone, and wrote the libretto for its first production, The Okavango Macbeth. He also co-founded The Really Terrible Orchestra, which performs regularly, and for which he plays the bassoon, in his own fashion: “I don’t like the C-sharp. It has odd fingering. So I tend not to play that. And the higher notes I don’t play.” The title is apt, he says: “We played in New York at Town Hall. I think we had 1,200 people there. And people got the joke—they loved it! They were waiting for us to sound awful, and we did.”

In 2006, he was named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire for his services to literature. Not to music.

In 2011, he was honored by the President of Botswana for services to the country.

In 2015, he received the Bollinger Everyman Wodehouse Prize for Comic Fiction, and in 2017, the National Arts Club of America Medal of Honor for Achievement in Literature.

He is often asked about his optimism. Dark things do happen in his books—there is disease and cruelty, wickedness and corruption—but ultimately they are always overcome by the good. Is that realistic? He admits ruefully that “sometimes I’ll go to mystery conventions, and real mystery writers don’t look like me. They wear dark t-shirts and look really cool.” But then he continues:

“If we take a hard-nosed look at the world, we could say, ‘Well, it doesn’t always work, and ultimately people will disappoint us.’ But that isn’t a particularly useful philosophy to get us through life. When I travel, I’m constantly meeting people who are exactly like my characters. They treat one another with respect and courtesy, and they lead their lives with dignity and good humor, although they often do so in difficult circumstances. Human life consists of the utterly bleak and suffering in all its varieties, and then on the other hand, it’s full of the potential for joy, for happiness, for fellowship and friendship and love. We need to contemplate the pathological. We need things to be sharpened up from time to time. But, at the same time, we shouldn’t forget that there are other things.”

___________________________________

The Essential McCall Smith

(No. 1 Ladies Edition)

___________________________________

With any prolific author, readers are likely to have their own particular favorites, which may not be the same as anyone else’s. Your list is likely to be just as good as mine – but here are the ones I recommend.

The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency (1998)

You must begin at the beginning, and McCall Smith does a stupendous job of introducing his main cast through character work, flashbacks, and cases. We get an entire chapter from the point of view of Precious’s father, Obed, and his perilous life as a miner in South Africa: “In that place, I felt every day I might die. Danger and sorrow hung over Johannesburg like a cloud.” We watch Precious growing up, tended to by a barren cousin whose husband had left her, and then the nightmare of Precious’s marriage. We ache for her and Grace as the agency gets off to an impossibly slow start: “The whole idea was a ghastly mistake. Nobody wanted a private detective, and certainly nobody would want her. Who was she, after all?…She had never been to London or wherever detectives went to find out how to be private detectives.”

But then we grin as the cases start to tumble, one after another: the bogus father she exposes with her nurse ruse; the husband who disappears in the middle of a river baptism; the imperious wealthy man who wants to know who his teenage daughter is seeing (“There comes a time when they must have their own lives. We have to let go,” she urges him. “Nonsense,” he says. “Modern nonsense.”); the woman who wants to know whose car it is her husband has stolen and how to get to its original owner; the wife convinced her husband is playing around (which doesn’t mean she is happy with Mma Ramotswe when presented with graphic proof that she is right); the worker who falsely claims by a bit of, um, sleight of hand that he must be recompensed for losing a finger on the job (she sets him straight: “There are some people in this country, some men, who think that women are soft and can be twisted this way and that. Well, I’m not”); and, most chilling of all, the eleven-year-old boy who vanishes, possibly killed to make a very old, very dark kind of witchcraft medicine.

“I thought I’d seen all the varieties of human dishonesty,” Mma Ramotswe remarks at one point in the book, “but obviously one can still be surprised from time to time.”

You will be, too.

In the Company of Cheerful Ladies (2004)

“Now you listen to me. I haven’t come back for you – don’t worry about that. I never really liked you, you know? I wanted a woman who could have a child, a strong child. You know that? Not a child who wasn’t going to last very long.”

This installment has a number of interesting cases—a crooked Zambian financier who must be tracked down; the truth behind poor Mr. Polopetsi’s imprisonment; the outrageous use to which Mr. J.L.B. Matekoni’s former house is being put and what to do about it – and they’re all fine. But it’s the personal dramas that make this book a standout:

* Grace’s despair when no one will ask her to dance (“It’s my glasses, she told herself. It’s my glasses, and the fact that I am a plain girl. I am just a plain girl from Bobonong.”), a situation not much improved when the awkward, stuttering man who will one day be her husband clumsily bumps her around the floor.

* Grace’s further humiliation when the last person she wants to see, the odious Violet Sephotho, she who got barely fifty percent on her exams, gloats over her own plum job—“I looked at the men who were offering the jobs, and I chose the best-looking one. I knew that that was how they would choose their secretary, so I applied the same rule to them! Haw!”—and then lowers her eyes to Grace’s feet, and smirks: “Those green shoes of yours. I’ve never seen anybody wear green shoes before. It’s brave of you. I would be frightened that people would laugh at me if I wore shoes like that.”

* Charlie’s infatuation with a fancy woman with a Mercedes-Benz, which bodes to end very, very badly when her husband finds out.

* But most of all, this is the book in which the terrified Precious Ramotswe comes head to head again with the man of her nightmares, the husband who beat her, left her, cost her the baby, and has lived in her mind ever since. Note Mokoti is there to blackmail her. He holds a secret that could devastate her life: “If you don’t pay, then maybe I can tell somebody—maybe the police.” She is not the same frightened little girl he used to know, however. Combining her detective skills with a new-found self-awareness, she demolishes him, and the reader cheers. You don’t want to miss it.

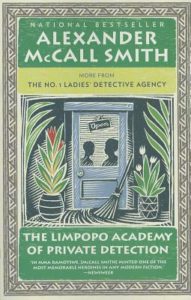

The Limpopo Academy of Private Detection (2012)

“Well, if that was the way he chose to conduct himself, then the gloves could come off. Do not take on a traditionally-built person unless you are prepared for a heavyweight bout.”

So much happens in this book. Mma Potokwane is wrongfully dismissed as matron of the orphan farm, supposedly for reasons of “savings,” but much more likely high-level corruption and greed. Fanwell, desperate for extra cash, is persuaded by an old classmate to help with some off-the-books car repairs, which turn out to be part of a stolen car ring, which lands him in court, his future bleak, being defended by the worst lawyer in town. Grace and Phuti are building their dream house, but their builder is steamrollering them on their contract and materials, and they sense that something is seriously off.

And Precious and Grace have a visitor—a private detective from Muncie, Indiana, named Clovis Andersen, who is in town for three weeks to visit a friend, sees their sign, stops in for a courtesy visit, and is astonished to find out they know his book: “I had no idea that my rather ordinary thoughts on investigation should be taken so seriously.” Ordinary or not, he provides key assistance with Mma Potokwane’s case, giving Mma Ramotswe the suggestions that enable her to hoist the malefactor by his own petard.

“What is a word, Mma,” says the smug villain. “Resigned, dismissed, retired; jumped, pushed, shoved out? All the same at the end of the day.”

“You can add to that list of words, Rra,” she replies quietly. “Add: betrayed, destroyed, tricked.”

And she lowers the boom.

Clovis has his own secrets, though. His past, his present, are nothing like what Precious and Grace imagine, and he is a man sorely troubled in spirit. It is now time for Precious Ramotswe to help him, and she does so with a kindness and gravity that will melt your heart.

___________________________________

Book Bonus: Series

___________________________________

McCall Smith really can’t help himself. Besides the No. 1 books, he has written to date five other series of varying length and nature.

The thirteen 44 Scotland Street books began as a serial in The Scotsman in 2004 and is now, according to his website, “the longest-running serial novel in the world.” Not everybody was enthusiastic about his agreeing to it. After McCall Smith accepted the offer, his publisher called him up and said, “Do you realize that writing a column a week is phenomenal pressure?”

“Well, actually,” McCall Smith told him, “it’s once a day.”

The title refers to a building in Edinburgh, and the books detail the adventures of all its tenants, which include a girl named Pat and her various roommates and neighbors, and most especially the scene-stealing Bertie Pollock. He is five years old when we meet him, a prodigy who can speak Italian, play the saxophone, and discourse on a wide array of subjects, but who really just wants to be treated like a normal five-year-old boy, a hope constantly thwarted by his mother, the appalling Irene.

The sixteen books in the Isabel Dalhousie series (including three original ebooks) center around the title character, the forty-something editor of The Review of Applied Ethics in Edinburgh, who, in the best amateur tradition, finds herself irresistibly drawn to the mysteries that cross her path, ranging from gold-digging fiancés and art fraud to possible homicide and any number of family secrets and dangerous affairs. Philosophy and ethics play a major part in her deliberations, as you would expect from a woman with her job, and names like Kant, Wittgenstein, Hume, Camus, and Bertrand Russell pop up frequently, but the books are full of the gentle humor and observations on human behavior that inform the Ramotswe books, and they have plenty of fans.

Two other series are much shorter in number. Corduroy Mansions is set in a fictional London housing unit, and its three books were all written online, a chapter a day, from 2008 to 2010, with invitations to the digital readers to offer him suggestions, some of which were incorporated. Portuguese Irregular Verbs consists of four academic satires featuring Professor Dr. Moritz-Maria von Igelfeld and his colleagues, all of whom inevitably become distraught about matters of no importance whatsoever outside their circle. This series first began as a bit of a joke with his friend Reinhard Dr. Dr. Dr. Zimmerman, with a print run of all of 500 copies, but it’s acquired a cult following.

If you want my real recommendation, though, for which series to try if you love The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency books as much as I do, it’s the Detective Varg books. I’m a big fan of Scandinavian noir—the novels of Larsson, Mankell, Nesbo, Fossum, Adler-Olsen, Indridason, and the great Sjowall and Wahloo, among others, and their books full of tortured detectives, psychotic villains, and crimes so terrible it astonishes you that anyone up there even leaves their houses anymore. Detective Varg deals with none of that. This is Scandinavian blanc.

Ulf Varg (both words mean “wolf” in Old Norse) is the head detective of the Sensitive Crimes Department of the Malmo Criminal Investigation Authority. It’s a small department, and their brief consists of crimes “at a rather odd end of the criminal spectrum. We don’t do murder and such things.” He’s kind, intuitive, intelligent, unfortunately in love with his married colleague Anna, and can “see a frayed shoelace in somebody’s shoe and spin from that an entire theory as to who that person was, what motivated him, what he did for a living.” The crimes they tend to look into in the four books so far (two of them ebook only), including The Department of Sensitive Crimes (2019) and The Talented Mr. Varg (2020), feature such things as a man stabbed in the back of the knee; a werewolf howl keeping guests at a spa up at night; an imaginary boyfriend gone missing, setting off an escalating cascade of incidents and miscalculations; and an infamous two-fisted, hard-drinking womanizer of an author—“Sweden’s Hemingway”—who may not be at all what he seems. These books are funny, poignant, oddball, insightful, and filled with matters of the heart and mind. You’ll want to try them.

___________________________________

Book Bonus: But Wait! There’s More!

___________________________________

Yes, indeed. Nearly forty children’s books, including five featuring the young Precious Ramotswe. Seven anthologies of short stories and African folk tales. Eight stand-alone books, including novels of World War II, a modern retelling of Emma, and a story about a man unable to find a rental car at an Italian airport, who gets fixed up by a stranger with the only vehicle available—a bulldozer. McCall Smith swears it’s based on a true story. Plus, various nonfiction, including an impassioned work, part memoir, part literary appraisal, about one of his heroes, What W. H. Auden Can Do for You. That’s not even counting his academic texts, twelve books published between 1978 and 2003 on legal and medical subjects, many of which are standard in their field.

So what did you do this morning?

___________________________________

Television Bonus

___________________________________

An absolutely wonderful all-too-short series of The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency was broadcast by the BBC and HBO in March and April of 2008. Anthony Minghella (best known for The English Patient) was the executive producer, directed the first episode, which was feature-length, and co-wrote the adaptation with Richard Curtis (Four Weddings and a Funeral, Notting Hill, Love Actually). Six more hour episodes followed.

It was all shot in Botswana, and you can tell. I had the opportunity to re-watch all the episodes while writing this piece. It tweaks some characters and story arcs, but it is filled with authentic sights and sounds and rhythms—the music alone is great. The producers (which also included Sydney Pollack, Amy Moore, and, sigh, the Weinsteins) were so sure of what they had that they signed a ten-year lease for an area at the foot of Kgale Hill in Gaborone, where they build the fictional shopping center where Mma Ramotswe first opens her detective agency. The government preserved the site as a tourist draw.

The unconventional choice for Mma Ramotswe was Jill Scott, known widely as a singer but less so as an actress, but Minghella thought she had true screen presence, and he was right. Starring next to her as Grace Makutsi was the splendid Tony Award-winning actress Anika Noni Rose, and if you pay attention you’ll see actors such as David Oyelowo (!) and Idris Elba (!!) pop up, along with a host of African and British-African actors.

You’ll never want the series to end. Unfortunately, that March, Anthony Minghella died of complications following cancer surgery. In May, Sydney Pollack died. The series won a Peabody Award, HBO mused about possibly doing a couple more feature-length episodes, but it never happened. You can, however, find it all on HBO Max. Go watch them now. It’s all right, I’ll wait.

___________________________________

Clovis Andersen Bonus

___________________________________

The reason Clovis Andersen was from Muncie, Indiana, was because Alexander McCall Smith went to a crime fiction conference there once, and loved it. Three hundred women were there, he recalls, all knitting. He was asked there, as he has been asked repeatedly, where a person could get hold of a copy of The Principles of Private Detection. It’s possible, he says, that he may just have to sit down one day and write it. In the meantime, here are a few choice entries:

“Don’t believe something because you want it to be true. Nor should you believe everything you read or are told by other people. Ask them for the evidence, and if they cannot produce it, then politely say, ‘I am unconvinced’ and leave it at that.”

- How to Raise an Elephant

“Remember that of all the possibilities you may address, the truth may lie in the simplest explanation. So if you are looking for something that is stolen, always remember that it may not be stolen at all, but mislaid. Similarly, if you are investigating a homicide, it is always possible that the victim died a natural death. Do not exclude this possibility even when the death seems very suspicious. I knew a man who stabbed himself to death. Everybody thought that he had been murdered, and they found plenty of suspects—he was one heck of an unpopular guy—but then they discovered a note in which he said that he was going to do this in order to make things look bad for his principal enemy. He even used his enemy’s knife to do it!”

- The Minor Adjustment Beauty Salon (2013)

“Be gentle. Many of the people who will come to see you are injured in spirit. They need to talk about things that have hurt them, or about things that they have done. Do not sit in judgment on them, but listen. Just listen.”

- The Kalahari Typing School for Men

“There are some cases where everybody tells lies. In these cases you will never know the truth. The more you try to find out what happened, the more lies you uncover. My advice is: do not lose sleep over such matters. Move on, ladies and gentlemen, move on.”

- The Saturday Big Tent Wedding Party

“Don’t think you can explain everything, because you can’t.”

- To the Land of Long Lost Friends

___________________________________

Gaborone Retailers Bonus

___________________________________

Judgment-day Jewelers

Go Go Handsome Man’s Bar

Make Me Beautiful Salon

Small Upright General Dealer Store

Honest Deal Butchery

Good Impression Printing Company,

Superior Positions Office Employment Agency

The This Way Up Building Company

Patrick’s Patient Driving School

Good Times First Class Bar

The Big Fun Hotel

___________________________________

The Important Thing

___________________________________

“But as she drove along the Mochudi Road, passing each landmark – that tiny rural school with the stony yard and the crumbling whitewash; that normally dry river course, now with a muddy trickle of water from the previous day’s rain; that graveyard just off the road with its tiny shelters, umbrella-like, above each grave, so that the late people down below might be protected from the sun—as she drove along this road with all its memories, she put out of her mind the things that had been worrying her. For out here, out in the acacia scrub that stretched away to those tiny island-like hills on the horizon, the concerns of the working world seemed of little weight. Yes, one had to earn a living; yes, one had to work with people who might have their little ways; yes, the world was not always as one might want it to be: but all of that seemed so small and unimportant under this sky.

The important thing, and really the only thing, Mma Ramotswe told herself, is that you are breathing and that you can see Botswana about you; that was the only thing that counted. And any person, no matter how poor he might be, could do that. Any woman might drive her tiny white van along this road and feel the warm breeze on her face. That was the important thing.”

- The Miracle at Speedy Motors

africa

africa africa

africa africa africa

africa africa

africa