When it comes to the Parker novels, which Donald Westlake wrote under the pseudonym Richard Stark, there’s pleasure in repetition. Many of the books follow a similar template: Parker, a career thief, plots an elaborate heist alongside a shifting cast of criminals; the heist is carried out but falls apart in some manner, with Parker left scrambling to survive and claim his money. You wouldn’t think that reprising the same plot-beats over and over again would work after the first few books, and yet it does—Parker remains an enduring character within hardboiled fiction. Why?

To be fair, not all of the novels slavishly follow the same template. For example, Slayground (1971) focuses mainly on the aftermath of a heist, and Parker trapped inside a closed-up amusement park as corrupt cops and the local hoods try to take him down (the similarities with “Die Hard” are stunning). Parker novels such as The Outfit (1963) play more like revenge thrillers than by-the-numbers heist novels, although our anti-hero always makes sure that he’s richer by each novel’s end.

Parker himself remains something of a cipher throughout the books. He’s the human equivalent of a large boulder rolling downhill: Unyielding, unstoppable, and perpetually in motion. There are none of the usual digressions into his background or deep-seated traumas that authors usually rely upon to round out a character. Westlake didn’t even give him a first name. That lack of conventional characterization would make a creative-writing professor’s head explode, but audiences have nonetheless made Westlake’s books into solid sellers for decades.

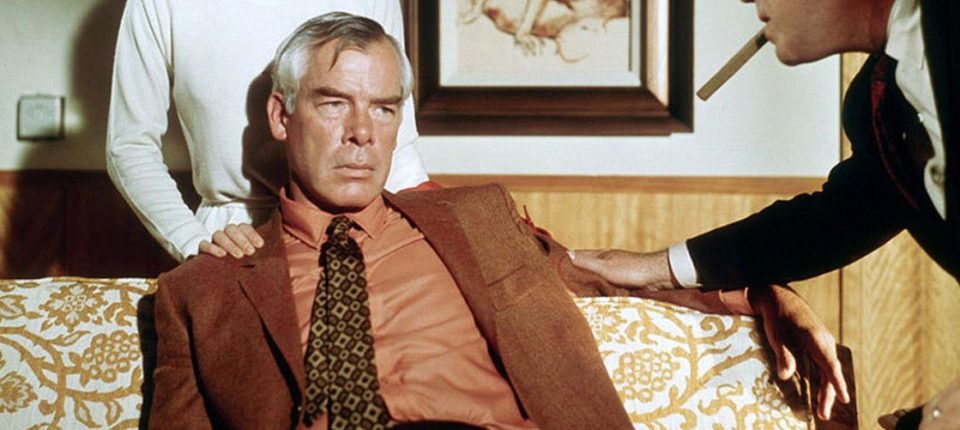

Subsequent authors have followed Westlake’s template with mixed success. Perhaps the most notable is Lee Child, whose Jack Reacher (25 novels and counting) also finds himself ensnared in some variation of the same scenario. Soon after arriving in a town (usually small, and usually via the bus), Reacher stumbles upon some vast conspiracy involving some combination of crooked businessmen, terrorists, or former military sorts. Bones are crushed; wrongs are righted; and Reacher—who, like Parker, is pretty much a two-legged bulldozer—eventually climbs back onto the bus, bound for his next adventure.

As with Parker, Reacher somewhat defies gravity: there’s no reason why repeating a formula again and again should work with the audience, and yet it does. The answer might lie in routine itself.

In On Writing, Stephen King dropped an interesting bit of advice: “People love to read about work. God knows why, but they do.” That certainly rings true when you take a quick survey of popular books, both fiction and nonfiction: Readers like having an authoritative voice take them through the particulars of a job, especially if that role is unusual or exotic. Think of Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential and its lengthy chapters about a restaurant kitchen’s routines (or even his culinary noirs, such as Bone In the Throat), or how Don Winslow’s books go into so much detail about drug cultivation and trafficking (which required years of research on his part).

The Parker novels are, at their most fundamental, books about work. A substantial percentage of each title’s page-count is devoted to Parker discovering his next heist, negotiating with partners, arranging for equipment, and figuring out how to most efficiently overcome any security or resistance.

Take Slayground, in which Parker is besieged in an amusement park. Most of the book is given over to Parker’s preparations for the eventual assault. He walks through the rides and attractions, testing and adjusting; in these passages, divorced of broader context, he might as well be a maintenance worker on his rounds:

“He had to work by flashlight, removing the wiring from several of the lights and fastening it carefully elsewhere. When he was done, he didn’t turn the display back on. He untied his boat, got back into it, and rode it the rest of the way through the ride. Since in stopping the boat he’d stripped it of its connection to the track, he was borne along by the water flowing through its winding metal trough inside the building, down to the end of the ride.”

Despite his literary reputation as a ruthless killer, Parker is an observer most of the time. In Backflash, he spends a big chunk of the book figuring out the vulnerabilities of a riverboat casino—again, with a keen focus on detail:

“Parker chose a Friday night trip, the same as the night they’d be taking it down, to get a feel for the place. The ship was full, action in the casino was heavy, and the people having dinner in the glass-walled dining rooms to both sides of the casino as it sailed past the little river towns were dressed up and making an occasion of it. The sense was, and it was palpable through the ship, this was a fun way to spend money. Good.”

Jack Reacher, in many of his novels, follows a similar template. In “The Hard Way,” Reacher helps a shady military contractor whose family has supposedly been kidnapped, and he spends much of the novel’s first two-thirds walking around Lower Manhattan, trying to determine the timing and nature of the kidnappers’ scheme. Like every book, there are frequent dives into Reacher’s craft. His job is an unusual one, and how he conducts it often overshadows the actual plot or villains of the piece (especially when he overwhelms all opposition relatively quickly).

The imitators of Parker and Reacher (and they’ve been frequent over the years) have generally leaned into the violence, sometimes resulting in excessive displays of testosterone that are inadvertently funny. To reach back to Stephen King for a moment: Alexis Machine, the Parker-like character created by author Thaddeus Beaumont in The Dark Half (who’s writing under the pseudonym George Stark, echoing Westlake’s pseudonym Richard Stark—there are layers upon layers here), is the perfect example of such a character taken to the wrong extremes. In the fragments of Beaumont-as-Stark’s manuscripts scattered throughout King’s novel, Machine growls out tough-guy pronouncements and threatens folks with a straight razor, and it’s all so over-the-top you can’t help but laugh.

In Parker’s case, Westlake avoids tumbling into this trap by having his man remain taciturn and efficient. Throughout the books, Parker relies on violence as just another tool in the course of his workday; he shoots and maims as judiciously, efficiently as he picks a lock or figures out an armored car’s schedule. It’s the detailed focus on his “work,” alongside the comforts of repetition that come with any well-crafted series, that have made him such an enduring figure, more than any spectacular kills he dispenses. He’s imitated, but never surpassed.