These are dark days for romance. Even if you are the type who usually buys into the schmaltzy hullaballoo of Valentine’s Day, you’re probably not feeling too lovey-dovey this year (and if you are, what the hell is wrong with you?) With the pandemic still raging and date-night hotspots shuttered, many of you will no doubt settle in to watch a movie at home, probably one all about love and romance, through which you can pine and swoon and live vicariously.

But all that’s likely to do is make the current day reality more bitter. So, instead of watching some cheap, over-lit Hallmark movie or Vaseline-lensed classic, why not embrace the darkness by indulging in something mean, sour and bloody?

To quote Pat Benatar, love is a battlefield, and these 10 films present romance as a war of attrition.

Double Indemnity (1944)

I wanted to stick to lesser known films for most of this list, but you simply can’t leave out THE great film noir romance of all time. The moment amoral insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) lays eyes on the slinky ankle chain worn by bored housewife Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwick), he knows they’re both toast. This doesn’t stop him from engaging in a torrid affair with her, nor going along with a plan to murder her husband and pocket the insurance money. Walter is doomed from the start, but he’s no simple sap—even though Phyllis is using him, it’s obvious that the heat they conduct is very real. It’s so real, in fact, that it can’t help but burn both of them down in the end.

Duel in the Sun (1946)

The first film that Martin Scorsese remembers seeing—and the one that made him realize he wanted to make films—this lush Technicolor western melodrama from King Vidor stars Jennifer Jones as the beautiful Pearl, a half white, half Native American girl taken in by her extended family after her father murders her mother in a fit of jealous rage. Her life doesn’t get any easier once she’s living with amongst her wealthy rancher cousins, as a ‘love’ triangle develops between herself and the family’s two grown scions of the family, conscientious lawyer Jesse (Joseph Cotton) and sociopathic scoundrel Lewt (Gregory Peck, who was even better at playing bastards than he was at playing heroes). It’s Lewt that declares Pearl as his own, jealously killing anyone who attempts to come between them. Although she despises him for his evil, abusive ways, she can’t help but love him back. This leads to a final desert gun battle between man and woman that was way ahead of its time in 1946 and which has lost none of its bloody, mythic power since.

The Night Porter (1974)

Italian director Liliana Cavani’s film about the doomed rekindling of a sadomasochistic affair between a concentration camp survivor (Charlotte Rampling) and a former SS officer (Dirk Bogarde) was initially derided as exploitation and even pornography, but it has since been recognized as a provocative masterpiece that gives full weight to personal and historical trauma of the Nazi regime, while conveying the complex psychological toll that fascism takes on both its victims and perpetrators. In her essay for the Criterion Collection, professor and author Gaetana Marrone explains that the “transgressive couple” at the film’s center represent predetermined roles assigned to them by power; their strength is to accept them.”

Natural Enemies (1979)

A Manhattan magazine editor (the recently departed Hal Holbrook) wakes up one morning and decides that he is going to murder his entire family and himself. He then spends his last day on Earth indulging his frustrated sexual appetites and recounting—to anyone who will listen—the long, painful dissolution of his marriage (which he uses to try to justify his homicidal fantasies). Back home, his clinically depressed wife (Louise Fletcher) starts to piece together his plan. This leads to an emotional confrontation between the two in which she reveals that, in spite of all the emotional turmoil they’ve gone through—and despite the very real danger he poses to her and their children—she still loves him. Is this enough to avert tragedy? Well, it is a ‘70s drama—and a particularly disturbing one, even by that era’s standards—so you can probably guess the answer.

Bad Timing (1980)

Nic Roeg’s Vienna-set mystery charts the tumultuous relationship between a neurotic, controlling psychiatrist (Art Garfunkel—yes, that Art Garfunkel) and his free-spirited lover (Theresa Russell), who’s just tried to commit suicide. The film’s promotional material dubbed it a ‘Terrifying Love Story’, while its own distributor called it “a sick film for sick people.” The latter description may be debatable, but the former is entirely accurate, as this dizzying tale of obsession, control and guilt builds to one of the most horrifying revelations in all of cinema.

Possession (1981)

Where even to begin this begin with this surreal arthouse nightmare—my personal favorite film of all time—from exiled Polish director Andrzej Zulawski? An emotional howl into the void following the collapse of his own marriage, Zulawski’s film tells the story of a British spy (Sam Neill) who returns to his estranged family in West Berlin only to discover that his wife (Isabelle Adjani, giving the greatest performance in all of horror) is planning to leave him for a mysterious lover. As husband and wife are driven into a state of mutual psychosis by their shared love and hate of one another—a psychosis that manifests through restaurant-clearing brawls, massive car wrecks, self-mutilation, murder and possibly even nuclear Armageddon—it becomes increasingly clear that there are powerful, inhuman forces behind it all.

The Hot Spot (1990)

An early entry in the 90’s noir resurgence, Dennis Hopper’s adaptation of Charles William’s ‘50’s pulp novel Hell Hath No Fury sees a would-be bank robber (Don Johnson) settle in to a dusty Texas ghost town and pose as a used car salesman while he plots a grand heist. Before he even gets settled in his cheap motel, he’s fallen into a love triangle with a kind, virginal co-worker (Jennifer Connelly) and his boss’s cruel, oversexed wife (Virginia Madsen). All the time, Johnson’s character struggles to retain some semblance of morality, pining for salvation through the love of a good woman even as he gives his body over an evil hellcat he knows will destroy him. The film plays with and subverts the well-worn Virgin/Whore trope by ultimately sending our anti-hero off into the sunset with the woman he despises, but also recognizes as his true soulmate.

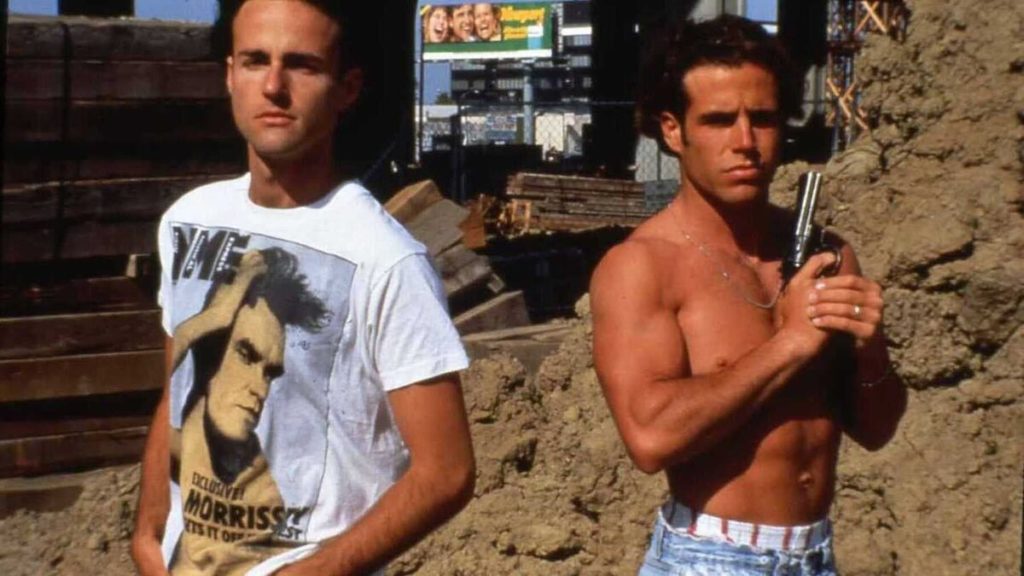

The Living End (1992)

Stepping away from breeder couples for a moment, we come to the debut feature from indie iconoclast Greg Araki, a radical queer spin on the lovers-on-the-run genre. Here, said lovers are a pair of HIV-positive gay men—a slacker film critic (Craig Gilmore) and a hunky homicidal drifter (Mike Dytri)—who meet by chance after the latter kills three gay bashers in self-defense. When he later murders yet another homophobe and a cop, the two embark on a road trip to New York, although their combative nature and violently opposed worldviews—one attempts to find some meaning in life, while the other is more than happy to embrace the random chaos of the universe—make it so that they don’t get far.

Szamanka (1996)

We return to Andzrej Zulawski, just as he returned to his native Poland five years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, for this visceral and hallucinatory tale about strangers—a brutish anthropology professor (Bugoslaw Linda) and a mysterious young student known only as The Italian (Iwona Petry)—who find themselves in a sadomasochistic affair, one that kicks off randomly but which quickly becomes literally all-consuming. A spiritual successor to Zulawski’s Possession, Szamanka (She-Shaman) mostly brooked comparisons to Last Tango in Paris upon its release. This is understandable, given its similar premise and graphic sexual content, but it’s a far more transgressive and extreme examination of sex and gender roles, thanks in large part to the script from Polish author and feminist Manuela Gretkowska.

In the Cut (2003)

Directed by Jane Campion and adapted from Susana Moore’s novel of the same name, In the Cut is a by turns dreamy and gruesome story of love, infatuation, misogyny and murder. Meg Ryan stars as an introverted New York college professor and potential police witness who falls into a passionate (and surprisingly kinky) affair with a gruff homicide detective (Mark Ruffalo). Even as the tryst leads to a sexual awakening, she begins to suspect her new lover—sensitive one moment, frighteningly aggressive the next—may in fact be the person responsible for decapitating several women throughout the city.

There are a handful of films from the past two decades that knowingly subvert the tropes of classic noir and psychological/erotic thrillers—Gone Girl is an obvious example—but this one is the strangest and most beguiling for the way it filters the romantic partner/potential killer premise—a favorite of Hitchcock’s—through a fairy tale lens and female gaze. While the film has its cult of admirers and champions, it deserves to be far better known, and there’s no better time to discover or rediscover it than this Valentine’s Day.