The scene had the air of a ritual murder. Her body was dressed in its best clothes, and paraded around for spectators to mock. He declared himself finished with her. He beheaded her in the garden, while the party watched. He broke a bottle of red wine, splashed it across her face. Then he stumbled, drunken, away, declaring later that he had no regrets. He had been “cured completely” of his “passion.” He spoke of his her as scornfully as he had once described her with tenderness and interest.

That “she” was a life-size doll, and “he” a living man, and a well-known Expressionist artist, is only part of the strangeness of this Pygmalion story.

*

Alma Mahler in 1910. Photograph: Imagno/Hulton Archive. Oskar Kokoschka, 1916.

But first, the boy meets girl: In 1912, a struggling young painter named Oskar Kokoschka chanced upon a lovely Viennese widow at a party. He watched her sing and play piano, and found her “young and strikingly beautiful” behind her mourning veil. He sketched her picture. He claimed later that the widow seemed “to have fallen in love with me at first sight.”

*

Girl meets boy: In 1912, after giving up on her own composing to raise a family, and the abrupt death of her five-year-old daughter, and the slow death of her husband, the widow Alma Mahler attended a party at her step-father’s house.

While she sang and played Liebestod, she noticed a “handsome figure, disturbingly coarse,” with an intense stare and a threadbare suit. He drew her picture. He pulled her into his arms in a “violent hug,” and within the day asked her to marry him.

Alma Mahler refused Oskar Kokoschka’s proposal, but not his passion. They became lovers. “Never before had I savored such convulsion, such hell, such paradise,” she wrote.

*

“Can’t you paint anything else but Mummy?” asked Alma’s eight-year-old daughter, standing in Oskar’s studio and staring at the many sketches and paintings on the walls.

*

“Too many guys think I’m a concept, or I complete them, or I’m gonna make them alive. But I’m just a fucked-up girl who’s lookin’ for my own peace of mind; don’t assign me yours.” -Clementine, from Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

*

Alma Mahler, 1899

Alma Mahler was one the most celebrated muses of the early 20th century, and a well-known socialite to a legion of famous artists, musicians, and writers in Europe and America. She was slightly more bewitching than beautiful, with her lidded blue gaze, her long nose, and amused mouth. Even in a static photograph, her face projects liveliness, judgment, mirth. She married three times, to Gustav Mahler (composer), Walter Gropius (architect), and Franz Werfel (poet and novelist). She bore four children; only one survived into adulthood.

Alma’s life—impetuous, exciting, and scarred by loss—has spawned numerous biographies and novels. The ones authored by women include: The Bride of the Wind, Ecstasy, and Passionate Spirit. By men: The Artist’s Wife and Malevolent Muse.

Alma’s own memoir: And the Bridge is Love.

*

Oskar Kokoschka, Die Windsbraut (The Tempest), 1913

Obsessive Oskar began spying on Alma’s apartment at night. He wrote her inflamed, contradictory letters. He painted and drew her incessantly. After months, Alma tired of it all. She planned a trip to Bohemia and made Oskar a bargain: if he created a masterpiece while she was away, she would marry him. It took Oskar the better part of a year to finish Die Windsbraut, which translates as “tempest,” literally “bride of the wind.” Two figures lie together against a stormy sea, the woman tucked against the shoulder of a man, who stares up with stricken eyes. The faces are Oskar’s and Alma’s. It is considered one of Kokoschka’s finest paintings.

But Alma did not keep her promise. Instead she decided that she and Oskar could only see each other every three days. When she discovered herself pregnant, she went to Vienna and aborted their child.

“In the sanatorium, he took the first bloodstained cotton dressing off of me and brought it home,” Alma wrote. “’This is my only child and always will be—’ Later, he perpetually carried around this old, dried up piece of cotton.”

*

In her mid-thirties, as the widow of Gustav Mahler, Alma led a comfortable life from her pension and her deceased husband’s royalties. Oskar, in his twenties, a rising artist with poor parents, lived hand to mouth. When the couple traveled together, Alma usually paid the tab. Marriage to Oskar would have stripped her of financial freedom. The birth of Oskar’s child would mandate their marriage.

*

Oskar Kokoschka, 1915

After Alma broke off the relationship with Oskar, he sold Die Windsbraut to buy a horse and joined the cavalry in World War I. In Ukraine, a bullet penetrated his skull. In Russia, he was bayoneted in the chest. Shell shock carved lesions in his brain and he lost the ability to walk. He recovered at a hospital in Vienna, persisting through painful therapy until his balance was restored.

In the hospital, Oskar began writing a version of Orpheus and Eurydice, casting himself and Alma in the starring roles. You remember the myth. Two lovers. The woman dies. The man goes to Hell to summon her back, but he doesn’t believe she will follow him out. After all, she’s already abandoned him once. Because he does not trust his beloved muse, she fades away. Forever gone. A tragedy. Another tragedy is that no one sees Eurydice as writing her own story.

*

Walter Gropius, founder of Bauhaus, Alma’s husband from 1915-1919

In 1915, with Oskar at the front, Alma secretly married Walter Gropius, a former lover and a financially secure, Teutonic male ideal besides.

When Viennese newspapers incorrectly reported Oskar’s death, Alma had her letters to Oskar removed by the bagful from his studio, to which she still had a key. She took a few sketches, too, and gave them to friends.

*

Franz Werfel, writer, Alma’s third husband

By the summer of 1918, Alma was deeply, illicitly, in love again, this time with Franz Werfel, the Jewish poet and dramatist. Franz, twelve years her junior, with his “large, beautiful eyes under a Goethean forehead” was equally smitten with Alma and likely fathered the child she was carrying. With her husband in Vienna, and Alma at her country chalet, Franz made many nocturnal visits to Alma. “We made love!” he wrote later in his diary. “I didn’t go easy on her.”

One night in late July, their violent sex made pregnant Alma hemorrhage. She was transported to a sanatorium in Vienna by hearse, the war having conscripted all ambulances. Only induced labor could save the child. By August, Martin Gropius was born, early. He would be Alma’s only son.

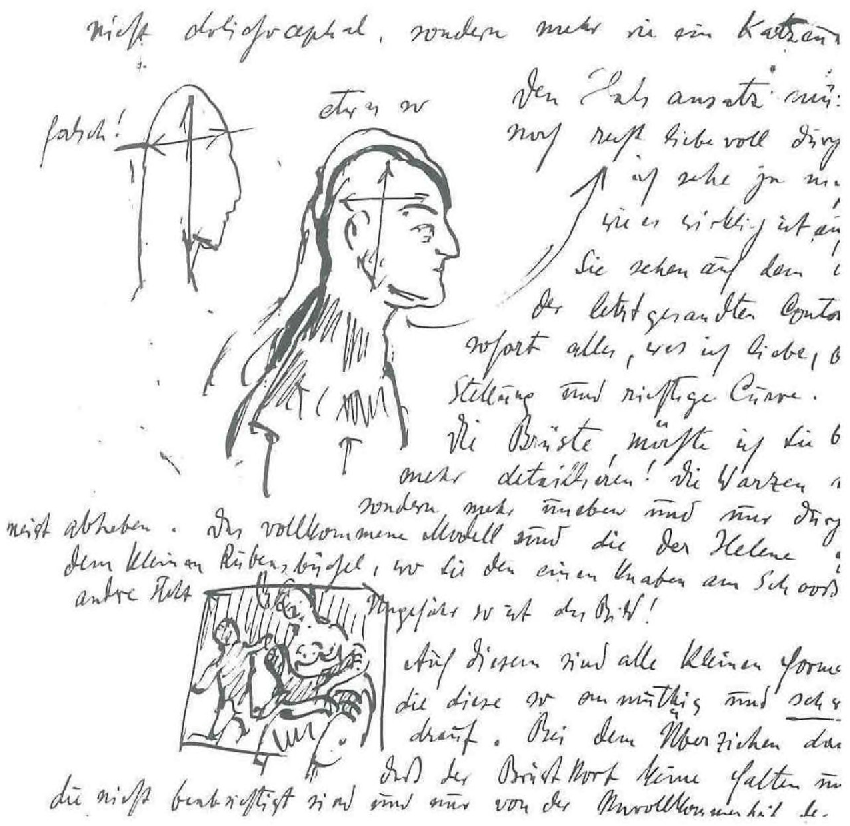

In those same months, the still heartbroken Oskar hit upon a bizarre plan to comfort his wounded psyche. He would commission a fetish doll in Alma’s image, to his exact specifications, and use the doll to expunge his creative soul of his former lover. After some searching, Oskar found an established female puppetmaker named Hermine Moos who agreed to the task, and they fell into a lengthy correspondence. Oskar’s letters, full of drawings and measurements, show the depth of his interest:

Although I feel ashamed I must still write this, but it remains our secret (and you are my confidante): the parties honteuses must be made perfect and luxuriant and covered with hair, otherwise it is not to be a woman but a monster. And only a woman can inspire me to create works of art, even when she lives in my imagination only.

*

Living in a man’s imagination was Alma’s specialty.

“He and I. I as spectator, boundlessly excited, so powerfully I had to lay a hand on myself,” Alma to her diary, appraising Franz’s sexual fantasy to play a cripple while she ravished him. “Now I am lying down and envisioning myself in such a situation… to bring joy to both of us.”

“I am tied to you. I sense a holy shudder gripping my soul when I talk about you.” -Franz

*

Oskar Kokoschka, letter to Hermine Moos, 1918

Oskar to Hermine Moos: “I beg you again… to breathe into her such life that in the end, when you have finished the body, there is no spot which does not radiate feeling.”

*

“You’re my downfall, you’re my muse,

My worst distraction, my rhythm and blues.”

-John Legend

*

“She had an uncanny knack for enslaving them,” Alma’s daughter said of her mother’s lovers. “And if anyone refused to become a slave, then he was worthless.”

*

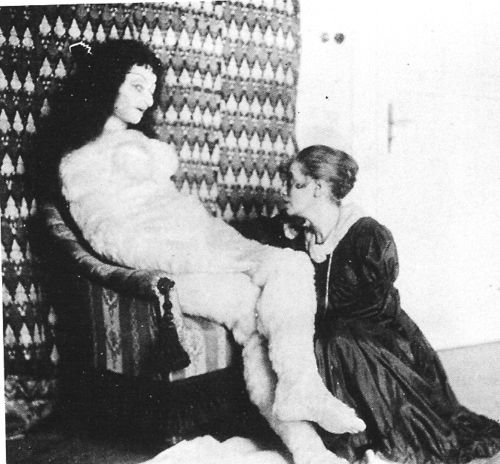

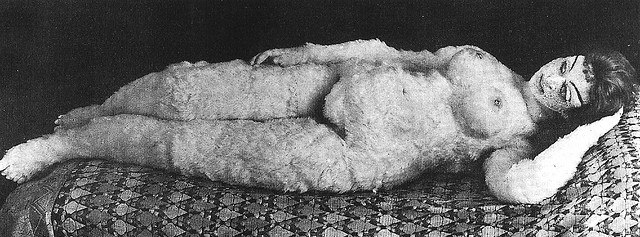

Hermine Moos with the “Silent Woman” doll, Munich, 1919 (University for Applied Arts, Vienna)

Little is known about Hermine Moos, the doll’s creator. She was a puppetmaker and painter, and the curvy, busty, feather-covered figure she made did not please Oskar Kokoschka when she delivered it in February 1919.

“The outer shell is a polar bear skin that would be better suited for a fake fuzzy bear bedside rug, but never for the suppleness and smoothness of a woman’s skin,” he scolded Moos.

Nevertheless, Oskar sketched and painted his “Silent Woman,” as he nicknamed it, and dressed it in rich clothes and lingerie. He spread rumors that he’d hired a cab to drive the doll around town and rented a box at the opera to show her off.

*

As Oskar was first unpacking his Alma doll, the real Alma was facing the sudden illness of her infant son Martin. An acute dropsy of the brain had caused the baby’s skull to swell to a massive size. In late January 1919, doctors advised a painful surgery to drain the swelling. It did not succeed. Franz extended his concern and care, but Alma withdrew from him, blaming his race and “degenerate seed” for the child’s condition. She placed Martin in the hospital; doctors told her he would not live long.

During that spring she heard from Oskar, whose pleading made her “full of longing” for him, but gossip about the doll might have paused her, because by May, she’d settled on Franz again.

Baby Martin died in May in the hospital alone, while Alma was traveling to see her husband. As far as biographers know, Alma never once mentioned her son, in diary or letters, after his death, and the whereabouts of his grave is unknown.

*

“Far be it from me to denounce Alma with the generally misogynistic insult ‘hysterical’; nor do I have the least intention of pathologizing. Alma was not ill; her life is no case history. But when one reads the scientific literature on the hysterical form of neurotic illness, certain parallels to Alma automatically come to mind.” -from the biography Malevolent Muse

*

Far be it from me to feel the need to state this again: Martin was Alma’s second child to die before the age of six. He was her only son, in an era that revered sons. His condition, hydrocephalus, makes a baby’s skull swell like a dome, with a tiny face at the base of it.

In the many online tabloids about Oskar’s sex doll, Alma’s life in those years is a series of steamy affairs. What famous man she bedded next.

Maybe she was a great lover and a middling artist and a bad mother, but Alma was indeed an artist who gave up her composing career to tend her husband and daughters, and then a widow, struck three times by loss. Some of the original Greek Muses bore children, too. The Muse of tragedy, Melpomene, gave birth to the Sirens, females known for seducing and destroying men.

*

In summer 1920, Oskar threw the doll’s death party, lit by torches. Champagne flowed. Oskar’s maid waltzed the puppet around, to loud jeers. The doll’s head broke, or was struck off. Her body was splashed or poured with wine. Her remains thrown in the alley. In the morning, police came, having heard reports of a maimed body.

It’s easy to imagine the crime scene, isn’t it? Splayed white limbs and red stains. A seductress’s fatal end and dismemberment. A neighbor staring into the shadowed street, fearing the worst, summoning the alarm. The police’s quick arrival. But the doll was a doll, a hollow thing. An object, then a rumor, then a joke, historical gossip, a symbol, a meme. Ugly enough for clickbait, erotic enough for a juicy headline.

One hundred years have passed, and Oskar’s debasing violence is more famous than ever. What of Hermine and Alma, the woman who created the doll, or the woman who inspired its image? Artist and muse, bound by male desire, then savaged by the same—how do we picture them that night, days later? Hermine, Alma, how did you respond? Did you laugh sharply, or turn to hide your face, when you heard of the trash the doll became?

*

“Don’t listen to the reasons and the ways of ignorant people who cannot know what we are good for and capable of,” Oskar to Alma, before the war. “You are the Woman and I am the Artist.”

*

“Every time I change wives, I should burn the last one,” Picasso to his former wife and muse, Françoise Gilot. “That way I’d be rid of them.”

*

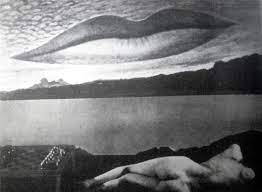

Man Ray, Observatory Time: The Lovers, 1936

In 1947, the posed, mutilated body of a young woman was found in a Los Angeles park, and became known as the Black Dahlia. Her murderer’s second act—to slice her body apart and arrange her limbs like art—was inspired by a photograph by Man Ray, claims a former LAPD detective named Steve Hodel, who is convinced his father was the killer and has spent decades proving the connection. “This is Dad’s surrealistic masterpiece.”

*

A handwritten memoir by one of Kokoschka’s neighbors scoffed at the wild stories surrounding the doll, claiming that Kokoschka had invented it all: the trips around town, the party, the ritual murder. It was all a fantasy, the neighbor said.

*

Dollmaker Hermine Moos committed suicide in 1928, at age 40, by swallowing veronal, a common sedative. Her motivations are unclear, although it is likely that she struggled career-wise after Oskar Kokoschka’s public disgust with her creation.

*

Alma and Franz

In 1929, at age 59, Alma wed Franz Werfel. As persecution of Jews increased throughout Europe in the 1930s, the couple made a dramatic escape through the Pyrenees and settled in Hollywood. Though their marriage was strained by Alma’s repulsive raving about German superiority, she protected Franz’s space and time so he could write his bestseller, The Song of Bernadette. She nursed him back to health after heart problems.

“How much I love you was not known to me,/Before the onset of these quick goodbyes,” he wrote to her in a poem. “Without him I cannot go on living,” Alma wrote in her diary. “He is the core of my existence.”

*

Franz died three years later. Alma outlived him by nearly twenty years and never remarried. She and Oskar remained friends, however, and penned sexy letters to each other in old age.

“How could we ever have separated!” wrote Alma. “Since we were made for each other!”

“If I ever find the time, then I’ll make you a life-size wooden figure of myself, and you should take me to bed with you every night,” Oskar promised. “We will get together again some time. Live for it, my unfaithful love.”

*

The Alma doll, 1919

Hermine Moos’s doll was not covered in polar bear skin, as Kokoschka accused, or the finest silk or linen, as he had requested—but swan skin, the feathers still on. The doll’s texture would have made it impossible for Oskar to fantasize he was touching a human woman, and difficult to dress the figure in fabrics. Instead, the puppet’s feathered surface emphasized its nakedness as a kind of completeness. A body whose barest state was also clothed and created.

Perhaps in defying Oskar’s instructions, Moos was paying a subtle tribute to Alma’s erotic quest, Alma’s love life the only art she could ever realize, her flawed masterpiece.

*

At Alma’s funeral, playwright Franz Theodor Csokor described her as “an energizer of heroes,” a woman “whose companionship stimulates her chosen man to the ultimate heights of his creative ability.” She was, he said, a “pure light, the flame of an Olympic fire.”

*

Alma, tell us!

All modern women are jealous.

You should have a statue in bronze

For bagging Gustav and Walter and Franz.

-from a 1965 chart-topping song by musician and satirist Tom Lehrer

*

“My life was beautiful. God gave me to know works of genius in our time before they left the hands of their creators,” claimed Alma. “And if for a while I was able to hold the stirrups of these horsemen of light, my being has been justified and blessed.”

*

Do you believe her? I do. Are you still seeing the headless doll in your mind’s eye? I am, too.

___________________________________