The late novelist Ed Gorman once talked about how excited he was when his first novel received a positive notice, one that included the phrase “transcends the genre.” He was very excited to have defeated the strictures and audience expectations of the mystery novel and to have created something new. Then he read the rest of the bullet-point reviews in the column and saw that three of the nine novels that week had transcended the genre. Well then, how hard could it be?

Crime fiction is far more capacious than people who don’t read the genre give it credit for. The field of play is so wide that it is difficult to transcend the genre, but it is possible to break it. A relative handful of exciting books are mysteries, are entirely in sync with the protocols of the genre and, and then at some point all of it falls away and the book is something else. Of course, the book doesn’t become something other than a mystery or crime novel—the third act of any book exists before the reader gets to it—it is that the writer broke the tropes of mystery, and created something that feels very familiar until a page turns and then it isn’t. Here are just a few examples. Of course there will be an unavoidable spoiler or two:

The Infinite Blacktop by Sara Gran

The Infinite Blacktop is not just the ultimate novel of Sara Gran’s Claire DeWitt series, it is the ultimate crime novel. When I was a bookseller, I loved hand-selling this title to mystery readers who wanted “something different.” I warned them, every time, that they might not want to return to more typically constructed crime stories after journeying to the climax of The Infinite Blacktop. DeWitt is fascinated with fictional teen sleuth Cynthia Silverton, whose own struggle to find the truth has more in common with holy hermits who abandon the world and all its passions than with a spunky amateur detective. DeWitt solves the mysteries she faces as well, as an afterthought. The Infinite Blacktop fries the mystery genre like an egg on hot asphalt, and serves that up, right off the road. It’s hard to enjoy normal mysteries after reading it, much the same way it is difficult to be wowed by a magic show when you’ve been shown the secret of every trick ever, in minute detail, by a real-life wizard. This is why, perversely, we placed it first on our list.

Carioca Fletch by Gregory Mcdonald

The seventh Fletch title (in publication, not chronological, order) doesn’t seem like a candidate for a genre-breaking mystery. Carioca Fletch isn’t even considered one of the better entries in the series. If cranky Amazon.com reader reviews are to be considered representative, many fans concluded that the entire book was a way for Mcdonald to turn a Brazilian vacation into a business expense for his taxes. There are hints of the supernatural at the beginning, when a widow claims that Fletch is the reincarnation of her late husband. More to the point is that Fletch encounters supernatural elements from Brazilian folklore, and he encounters them before he is told what they are by the locals. Magic and myth play no role in other Fletch novels, and honestly, mystery plays only the slightest role in Carioca Fletch. The skills of an investigative journalist are necessarily superfluous in the situation Fletch finds himself in—so, this book, which is as funny and as well-observed as any in the series, becomes an anti-mystery doppelganger of a Fletch book, in much the same way Fletch himself is a doppelganger of the long-dead Janio Barreto.

The Ruined Map by Kōbō Abe

A detective with no name, a beautiful woman, a missing husband, a suspicious brother-in-law, and a tantalizing number of objects, coincidences, and hints as to what happened. It’s a set-up so obvious you can write the end yourself in an afternoon. There are at least three satisfying possibilities, ones so obvious, so satisfying that author Kōbō Abe refuses to write any of them, or any other ending. Not only will there be no answers, even the questions will be treated with upmost suspicion. “Putting forth such speculations served no purpose at all,” the detective declares at one point, and it is one of the last things he is able to declare with any confidence at all. The narrative universe in this minimalist mystery is tiny, but as the title suggests, there’s no way to truly navigate it, or understand what has happened, no matter how closely the sleuth, or you dear reader, pay attention to the clues.

A Scanner Darkly by Philip K. Dick

An exquisitely paranoid near-future (nearer every day!) science fiction novel by the influential master, A Scanner Darkly is also a police story. Bob Arctor is deep undercover as a vague blur named Fred, trying to infiltrate the druggie counterculture and find the source of the mysterious Substance D. It doesn’t take long for Bob to start spying on himself without even realizing it, and that is only the first of many layers of deception, new and swapped identities, and intractable mysteries. The book is also famously autobiographical. There is a non-fiction coda cum dedication in which the author lists the first names of his many friends and acquaintances whom were killed, harmed, or left entirely insane by drugs. Conspicuously present—the name “Phil”, a fellow whom we are told was let off fairly easy by his drug addiction, suffering only “permanent pancreatic damage” and certainly not “permanent psychosis” like so many others on the list.

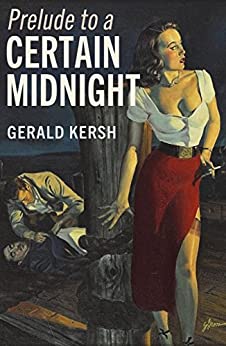

Prelude to a Certain Midnight by Gerald Kersh

After a young girl from the lower social orders is murdered, the police care not at all, so it is up to the posh busybody Asta Thundersley to invite all the suspects to a dinner party and unmask the murderer. But how would this premise actually work out in real life, given what we know of posh busybodies and dinner parties and the murder of street urchins in hierarchal society? Not well. Some have called this novel a satire of drawing room mysteries, but in fact Prelude to a Certain Midnight is utterly dedicated to literary realism. Mystery as a genre offers a type of fantasia, a world of wish-fulfillment where facts and reason, logic and determination, invariably deliver justice. But what if mystery wasn’t a subset of just-universe fantasy? Then they would all read like this book.

Rip-Off Red, Girl Detective by Kathy Acker

This short novel by the transgressive postmodern plagiarist Kathy Acker isn’t a joke, isn’t an overwritten travesty of hardboiled motifs and language, isn’t a bizarre experiment—it is a real-deal noir mystery with a sleuth and dead woman, a connection between the two, travel through a cityscape riven by class division, extensive flashbacks that serve to illuminate the sleuth’s (mostly sexual) personality quirks, and all the other tropes you could find anywhere from the classics of the genre to the forgettable paperbacks your creepiest great-uncle kept under his bed until he died and the body was carted away to a potter’s field by the city. It even has a genre-approved solution to the crime, and a noir denouement that will satisfy nobody. What makes it a genre-breaker is Acker’s pure intensity: imagine playing the audiobook versions of the top fifty all-time noir novels simultaneously, while the soundtracks of the fifty most popular PornHub videos occupy your left ear. Bonus: too short to be economically published by itself, Rip-Off Red is bundled with The Burning Bombing of America, which performs a similar trick with the genre of Cold War-era science fiction.

***