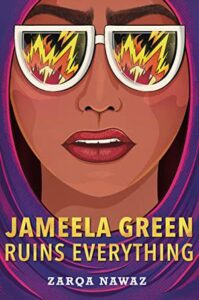

Zarqa Nawaz is as smart as she’s funny, and that’s saying something, since she’s very funny. Nawaz first became known for her hilarious and heartwarming sitcom, Little Mosque on the Prairie, and now she’s embraced fiction writing with her new novel, Jameela Green Ruins Everything, in which a woman prays for a book deal, accepts a mission from an imam to perform a good deed, and somehow finds herself in conflict with the CIA. Zarqa Nawaz was kind enough to answer a few questions over email.

Molly Odintz: The premise for this novel is wildly inventive. What was your inspiration?

Zarqa Nawaz: When my memoir, Laughing All the Way to the Mosque, didn’t make it to the New York Times Best Seller list, I became a little cynical towards life. It was 2014 and ISIS had just emerged and was dominating the headlines. Muslims are forever fighting the PR war when it comes to their image. Political pundits were opining that radical Islamic jihadists were the norm in Muslim culture. I knew there was a deeper story behind ISIS, especially from the one the media was portraying. I started doing research and the novel began to emerge—a bitter writer, reeling from professional failure, gets embroiled in an ISIS like group and a series of unfortunate events ensue.

MO: You’ve written a television show, a memoir, and now a work of fiction. How’s it all compare?

ZN: Story is at the heart of each medium. The television show, Little Mosque on the Prairie, came out of my lived experiences growing up in a mosque culture but during production, there’s a story room, a team of writers who work together to craft each episode. There’s such a joy, working on a show collectively, coming up with ideas, helping each other out of story predicaments. After I finished my memoir, I asked my editor when we could hire a team of writers to help make the book funnier and she gave me an odd look. It’s very scary to write on your own after working on a show. But the reviews were positive which gave me the courage to write my first novel. Writing a novel is also a solitary experience but a more complex one. Television is very plot driven and characters don’t change, especially in series television. In a novel, characters go through an emotional arc and have interiority. That’s why some novels don’t translate well into television and film, too much of the novel is in the character’s mind. I loved finding the balance between plot and the interior life of each character. Each medium has different challenges, but I love discovering new things about story as I write.

MO: You write in this book what seems to be the message of Little Mosque on the Prairie as well:

“I thought a funny book about the life of an ordinary Muslim woman would help the world see us as regular people, just people who may have stricter parents. If female Muslims exist in literature, it’s usually as a victim of Muslim men, who are portrayed as being brutal and violent.”

Little Mosque on the Prairie was the first show I’d ever seen that presented Muslims as regular people, and paved the way for a new generation of positive representation, but there’s still a great deal of storytelling out there that relies on harmful stereotypes as plot devices. How are things different now than when you first created Little Mosque on the Prairie, and what feels the same, in regards to Muslim characters in fiction?

ZN: I think much has changed in fiction. We are seeing many more books being published by Muslim authors such as S.K. Ali, Uzma Jalaluddin, Sabaa Tahir, Fatima Faheen Mirza and Ausma Zehanat Khan. These stories range from romantic comedies to Muslim cop stories to alternative fantasy fiction. There’s been a movement in publishing, #OwnVoices—a term that was coined by YA author, Corinne Duyvis. It encourages publishers to have accountability and publish books from underrepresented/marginalized groups written by an author who shares the same identity and perspective. The result is authentic representation.

MO: Humor is so important to your writing. It seems to me that satire is better than pathos when it comes to effective social criticism. Would you agree?

ZN: Yes, humour is an effective tool to communicate. When People laugh, they’re more willing to engage with an issue. If I had written a 300-page treatise about botched American Foreign Policy in the Middle East, people would have said, no thanks, but instead a wide range of people have told me that they enjoyed reading an international spy novel while simultaneously learning about history. So it’s a win, win for everyone.

MO: This book is definitely going to be described as “irreverent.” What did you want to explore about a playful attitude toward religion?

ZN: Religion is either taken too seriously or it’s mocked in entertainment. I’m tired of books that show a Muslim’s relationship with Islam as binary, a strict faith that’s oppressive or a faith that one needs to escape from in order to be liberal. Why can’t you be a practicing Muslim who enjoys life, is fun to be around and respectful of other people’s faiths and life choices?

MO: Jameela Green’s story illustrates how quickly one can turn from public citizen to public enemy. What did you want to explore about the vulnerability of the Muslim community to government targeting and harassment?

ZN: The book that inspired me was Monia Mazigh’s Hope and Despair. Her husband, a Canadian citizen and telecommunications engineer, had disappeared after boarding an American Airlines flight to New York, on his way back to Canada from a vacation in Tunisia. He was deported to Syria on suspicion to terrorist links by American immigration officials where he was tortured for over a year while Monia started a campaign to get him back. The Canadian government was complicit in dragging their heels to rescue him. The idea of Ibrahim’s disappearance in the book was inspired by this story. If this could happen so easily to a Canadian citizen with no proof or evidence, how many other people had it happened to? If it hadn’t been more Monia’s relentless activism to get her husband back, he would have died in a Syrian prison.

***