It’s not often that you meet someone who has expertise in something that both fascinates and terrifies you, but that’s how I felt when I arranged a date with Vegas Tenold, the author of Everything You Love Will Burn: Inside the Rebirth of White Nationalism in America. As I read the book it struck me that Tenold probably had precisely this feeling during the years he reported and wrote this book, years of attending meetings and rallies and even a cross burning or two. The book is the culmination of pieces he wrote for Al-Jazeera America and The New Republic, reporting on people and groups to the right of the alt-right.

When I asked about the genesis of the book, the Norwegian Tenold said, “I guess I started it early 2011 as a project for Columbia Journalism School. It’s not like I stepped out with the intention of writing a book from day one. Then I got access and it snowballed and I kept writing about it and exploring it. Then, two or three years ago, I started really thinking about it as a book.” In the book Tehold documents the activities and ideals of three far right groups, who have similarities as well as differences: the KKK, the National Socialist Movement, and the Traditional Workers Party.

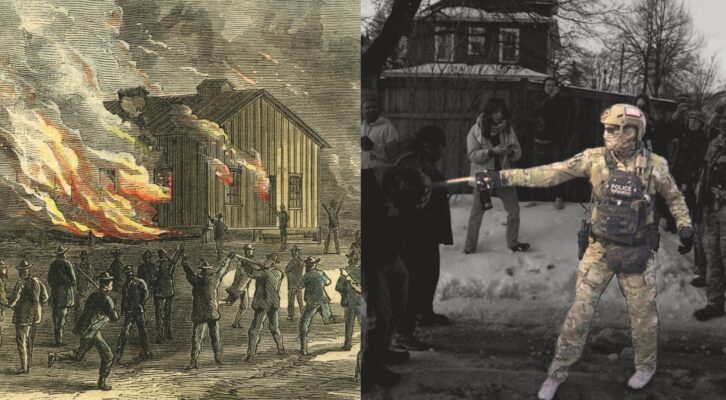

“My first group was the National Socialist [Movement], they’re interesting. But they’re also very reactionary. They’ve kind of stuck in the past,” Tenold told me. By stuck in the past he means that they are still into Nazi ideology and paraphernalia, giving the Hitler salute and wearing swastika tattoos. The KKK, too, has had trouble keeping up with the times: even though they still get press, and have a few well known national members like David Duke, the KKK hasn’t really adapted to 21st century life. A lot of them are proud off the grid types, who don’t want any government intervention in their daily lives. Tenold said, “People sometimes ask me what dangers these guys represent? The Klan is never gonna come back like they were in the twenties or during the Civil Rights era. We probably won’t have neo-Nazis by the thousands marching in our streets, so, no, these guys aren’t a direct threat but at the same time, their way of thinking and their talking points and their ideologies somehow managed to seep into the right. And, although, they keep fucking up their rallies, it doesn’t mean that we didn’t just elect a President who is taking stuff out of their ideological grab bag. So, we shouldn’t get too cocky with these guys.” The rallies Tenold refers to cover the events he attended in the book, from local community group meetings to supposedly major protests where maybe ten people show up. “Even those guys in the book are wildly uncomfortable sitting next to some of those people there. So, that’s a huge problem. There are always endlessly flowing rallies and small turnouts.” Like a lot of groups, white nationalists look a lot stronger on Twitter than they are in real life.

The star, or maybe anti-hero, of Tenold’s book is a 26-year-old Ohio man named Matthew Heimbach, nicknamed “the Little Führer.” Heimbach, whose group is the Traditionalist Workers Party, is on a quest to unite the far right. Tenold said, “I met Matthew Heimbach in the middle of 2015. At that time, he was kind of like a rising-ish star.” Heimbach, smart and charismatic, guided Tenold’s research and made the introductions necessary for him to do this reporting. “When I met him, I just got interested in how he kept maintaining that he wasn’t about white supremacy. He kept saying things like, ‘The white race could be the dumbest, worst race on the planet, but they would still be my family.’” Yet Heimbach is not above boasting or hair splitting: “He claimed to have been supported or to be endorsed by the Nation of Islam because he was a supremacist. Then, he would say that ‘I’m not a racist. I’m not a supremacist. I’m just saying they should want to be on their side.’” By “they” Heimbach means all people of color, Jewish people, the LGBTQI community, and anyone else who doesn’t meet their definition of white. Tenold’s subjects are the people who want to form white-only clubs in schools, or white student unions in colleges, asserting they are a race whose identity is being ignored in the face of multiculturalism, a concept they vigorously oppose.

“He took me through the shrubbery of the far-right. After a while, it kind of became clear that I was working with strange white nationalism, and the very American nationalism and white supremacy of the KKK.”Heimlich thus became a tour guide through this world for Tenold. “He took me through the shrubbery of the far-right. After a while, it kind of became clear that I was working with strange white nationalism, and the very American nationalism and white supremacy of the KKK.” Heimlich also introduced Tenold to “the kind of Hitlerian nationalism of the National Socialist Movement, where there are swastikas and that kind of thing, and then this new hybrid thing of Matthew’s, this thing that would eventually be known as the alt-right.” Tenold elaborated on Heimlich’s ideology. “His philosophy used to be fascist and I guess it’s national socialism now. He is a fierce anti-Semite. He is a white-separatist. He’s a racist. But, he somehow manages to do it in an exciting new way. I think it’s interesting that even for all his newness—in a way, he’s different—he inevitably fell into the old -isms of the far-right.”

Then it was time to talk about the elephant in the room of America: Donald Trump. I asked Tenold what these groups thought of the president, and the answer surprised me. Tenold explained, “I think a lot changed with Trump. That’s certainly when people’s eyes were opened. When I started, the Tea Party was about as extreme as it got. And we were talking about them as the people who burned down Washington. So, no one was really talking about white supremacy that much in 2011, 2012. And it always seemed like sort of a kooky niche.”

That changed as Tenold reported the book. “I would say around 2015 we went to a Donald Trump speech and that I thought, This guy’s an idiot. There’s no way we’re gonna elect him and it all will be what it is. Shortly after that, when he really started dog whistling, I think the far-right recognized their talking points. They recognized that and what Trump was saying. I think that’s when they were like, ‘Wow, this is kind of our moment. This is for all his flawed laws.’ I think many on the far right recognized him as a flawed candidate, yet they still saw him as, ‘This is our President. This is for our country.'”

But the far right would soon be disappointed in Trump. “That whole honeymoon ended fairly quickly,” Tenold said. “We all came into 2017 with this is going to be the year of the far-right. And their main challenge is, how do we mobilize this? How do we take this victory, how do we take this, for the most part, online movement that we’ve built and turn it into something that we can use and that’s lasting? And, I think, in most respects, they failed. Their relationship with Donald Trump got off to a rocky start. He bombed Syria. I believe it was with some missiles in March.” This set off the isolationist faction of the far right, who do not think America should get involved in other country’s problems. Tenold said, “That was the one thing he promised, not to bring America into any new wars. And the far-right Americans are very isolationist…So they see that as a betrayal. When Trump released his budget and slashed all the money for Appalachia, that was a blow as well. So, I think they felt that Trump became a Republican a lot quicker than they had planned.” Tenold continued, “I also think they didn’t see Trump as their guy, not that he wasn’t the perfect Nationalist candidate, but he was a foot in the door and even if he failed them relatively immediately, they would still use the momentum that he had given them to build upon. Now, whether or not they have been able to do that in 2017 is a different matter. I would argue that they haven’t. But, it’s been a number of relatively spectacular failures. But, they still saw 2017 as a step up regardless of how their relationship with Trump would go.”

Out of curiosity, and because I read a lot of Nordic noir, which addresses their version of white supremacy and the backlash against immigration, I asked what Tenold thought the differences were between American far right groups and the parties that have risen in his native Norway which oppose immigration and hold other racist ideals. Tenold said, “I think the refugee crisis of the last couple of years has been a tremendous boon for them because, all exaggerations aside, it’s been hard for European countries to find a way to deal with it in a way that doesn’t freak out the whole population. And the problem with anti-immigration partly is the populist argument of these guys are coming here to take things from us and posing a challenge or even a threat, is that it’s a very easy argument to make. It’s s a very easy argument to make because it appeals to our base selfish instincts.” Tenold paused, then said: “It’s difficult for us, on the other side, to say that yes, there are challenges, but we live in a world where we have to help each other and the long-term effects of immigration have been shown to be good and positive and all that kind of stuff. Populism is easy. Anti-populism makes it hard. Populist arguments are simple, easy, digestible.”

I asked Tenold for his working definition of populism, since it plays a large part in the book and in our conversation. He said, “Populism to me, in these days, it’s very much like the world has zero subtext. They win if they get anything from us and we lose, right?”

“And ‘they’ is anybody who is other,” I said.

Tenold agreed, “It’s our team. Anyone who is outside of these borders, they don’t count. I feel like there is this sense of dread all over the world that things aren’t as good as they used to be economically. Everyone seems to be genuinely losing their minds a little bit.”

Despite being sanguine about how fractured the American far right actually is, Tenold does feel like, worldwide, things are getting worse. Tenold elaborated on his gloomy feeling, “I think there is a selfishness. It’s kind of pervasive. I read somewhere that ours was kind of the first generation whose leaders haven’t served in a major war. So, we lack the idea of sacrifice and pulling together…the people in power right now came up in the baby boomer generation. Everything’s kind of been great and everything’s been handed to you, to us. We have no sense of shared sacrifice. So, maybe that’s why it’s easier for us to be like this. We had nothing. We had no defining moments to bring us together, to go like, ‘Wow, I’m me and you’re you but we have to work together this time.’ I don’t think we’ve had that. I think that’s made us into fighting, spoiled, selfish people.”