“Are you trying to bust my balls?”

The speaker is Inspector Salvo Montalbano, head of the fictional municipality of Vigàta, Sicily’s, police department, and in the 28 novels and two short story collections written by Andrea Camilleri and published in Italian and English…someone always is.

The criminals, from petty to monstrous, who occupy his frustrating days (and sometimes alarming nightmares); the Mafia thugs who spread their tentacles into every Sicilian institution; the corrupt politicians who march hand in hand with them; the witless press that blindly supports whatever government is in charge at the moment; the colleagues who, for all their police skills, can’t help but complicate his life at times; the suspicious Commissioner who seems intent on complicating his life at all times; the lady friend in Genoa with whom he can’t seem to get through a phone conversation without squabbling; the succession of beautiful women he meets during his cases who offer serious temptations and, all too often, deceptions – all these people light his fuse, but do not deter him. With a mix of sardonic humor, cynicism, stubbornness, compassion, a nose for crime, and a very personal sense of justice, Montalbano dyspeptically perseveres through all the tragicomedy that imbues his beloved island, reminding us that incidents – and people – are often not what they seem, and that sometimes refusing to obey an order is a virtue, not a sin.

Salvo’s mother died when he was young; his father, a man of few words, found it difficult to communicate; and Montalbano struck out on his own as soon as he could. Our first glimpse of him as a lawman comes in the novella “Montalbano’s First Case,” which Camilleri wrote later to fill in some of the blanks (Montalbano’s First Case and Other Stories, 2016; for clarity’s sake, all pub dates listed here are for the first U.S. publications).

Montalbano is 35, a deputy inspector in the inland town of Mascalippa, “a godforsaken backwater in the Erean Mountains,” where the crimes are “all without mystery: Luigi shot Giuseppe over a matter of money and confessed; Giovanni knifed Martino over a question of adultery and confessed.” When his boss, “a true cop,” gets promoted, and the higher-ups want to give Montalbano his job, Salvo panics at the thought of getting stuck there, until the boss wisely persuades his superiors to transfer Salvo to the port of Vigàta instead, where he blossoms.

He also finds out what it is to be a commissario in a town ruled by two warring Mafia families, the Cuffaros and the Sinagras, “a struggle that yielded at least two killings a year, on each side.” And he discovers where his true moral compass lies when a teenage girl, raped at fifteen, hatches a desperate and complicated plan to kill her gangster rapist, while deceiving Montalbano and his colleagues as to her real intent. Despite the fact that “she led us around by the nose, and took us exactly where she wanted to go,” Montalbano presses no charges and delivers his own brand of justice by making sure the thug’s disapproving crime family knows exactly what happened, and leaving the man to their not-so-tender mercies. There are rules, he says to Sergeant Fazio, but rules area meant to be adjusted.

“So that’s how you see things?”

“That’s how I see things.”

By the time of the first novel, The Shape of Water (2002), Salvo is 44, and has been running the department for several years. He has a house on the ocean, and a terrace facing the water, where he happily drinks his morning espresso and eats the meals his housekeeper Adelina prepares for him – for Montalbano, food is one of the greatest pleasures known to man, and the books are filled with his favorite dishes, both at home and in the trattoria he haunts for lunch every day, usually stuffing himself so full he has to walk it off afterwards.

Adelina’s only drawbacks are, first, that her two sons are constantly in and out of prison – Montalbano himself has arrested the youngest, Pasquale. Nevertheless, Salvo has an affection for the boy, which is returned. More than once, Pasquale has given him a tip in confidence (“I don’t wanna a reputation for being a rat” (The Wings of the Sphinx, 2009), and has even named Salvo the godfather to his baby. Another time, spotting a sex doll in Montalbano’s house that is a key clue to a murder in Treasure Hunt (2013), he gets the wrong idea – Montalbano had simply not known where to stash it – and tells him, “if you wanna nice-lookin’ girl, alls ya gotta do is gimme a ring…Guaranteed clean and healthy. An’ free o’ charge, since it’s you.”

The other drawback to Adelina is that Salvo’s girlfriend, Livia, can’t stand her, and the feeling is mutual. This means that any time Livia flies down from Genoa to see him, Adelina refuses to come to the house, and, alas, Livia is many things, but she is not a cook. She thinks she is, though, and whenever she prepares something, Salvo knows he has to eat it or there’ll be hell to pay.

This is pretty much the state of affairs with everything concerning Salvo and Livia, unfortunately. They love each other very much, and there are a host of tender moments in the books, but she’s as prickly as he is, and it doesn’t take much, “the tiniest thing, the wrong word, a minor angry outburst” (The Wings of the Sphinx), for them to spiral into slammed doors and phones: “This animosity remained independent of the unshakable intensity of their relationship. But then why, when talking on the phone, did they quarrel, on average, at least once every four sentences?” (The Smell of the Night, 2005).

Part of the problem is that they’ve already been together for six years in the first book, and as the books, and the years, progress, the question of marriage is very much on her mind. Every now and then, Salvo actually proposes, but she tries to pin down “when?” and never gets a straight answer. Montalbano can’t even give himself a straight answer. After one of their breakups, he asks himself what he feels for her: “Attraction. Desire. Vanity. Or else you see her as a kind of life raft you desperately want to grab hold of to avoid drowning in the sea of old age” (The Age of Doubt, 2012).

The situation gets worse when, during the course of a case in The Snack Thief (2003), an orphaned Tunisian boy named Francois comes into their lives, and Livia is determined they adopt him. Through various circumstances, it becomes impossible, but she blames Salvo for it, and when, many years later, in A Beam of Light (2015), the boy, now a man and a militant fighting the Tunisian government, is killed, she never really recovers from it.

Finally, two books before the final volume, she breaks it off for good. Salvo mourns: “It was love. Old and threadbare like a worn-out suit, with a few holes here and there, patched up as best one could, tired, but still love” (The Sicilian Method, 2020).

But he recovers. The reason is one of the other things that may have gotten Livia fed up with him: Salvo is always meeting women who knock him for a loop. Usually, nothing unforgivable happens… but not always. And sometimes those temptations arrive with a full agenda of their own.

Where to begin? With Ingrid, the beautiful Swedish woman, married to a politician, who becomes his “friend, confidante, and accomplice,” but also, when a little too drunk to drive, chastely shares his bed while he sweats? Or is it always chaste? There’s a strong hint otherwise in The Potter’s Field (2011). With Adriana, the twenty-year-old twin sister of a murder victim in August Heat (2009), who seduces him as a way to get to her sister’s killer? With Angelica, the burglary victim in Angelica’s Smile (2014), who seems to know an awful lot about him before she takes him to bed, and who turns out to be one of the burglary gang herself? With Rachele, a champion equestrian in The Track of Sand (2010), who literally gives him a roll in the hay? With Liliana, the next door neighbor in Game of Mirrors (2015), who is in league with the Cuffaros and ends up getting gruesomely killed by the Sinagras?

No, let’s go with the reason Salvo recovers from the final Livia breakup: Antonia Nicoletti: beautiful, whip-smart, the new head of Forensics who’s been temporarily transferred from Calabria for clashes with her colleagues (“it’s a long story”), and happily single (“I still haven’t met [a man] I’ve liked enough to want to have around every day”). He feels a deep, deep connection with her, so much so that when she does get her new assignment, he proclaims he’ll transfer or resign and go with her. To which she stuns him by replying, “Have you asked yourself if I want to live with you? If I feel the same way about you? If I also want you by my side in the future?”

Well…no. Crestfallen, he goes to the train station to say goodbye, they talk, they hold hands, the train starts to move, their grip gets tighter, the train is gone, and they’re still there. “What now?” Montalbano manages to ask. “Now we’re here,” she replies.

What does that portend for Salvo and Antonia? We’ll never know. The next book is The Cook of the Halcyon (2021), a somewhat slapdash adaptation of a ten-year-old film script for an Italian-American movie that never got made. “For better or for worse,” Camilleri’s author’s note says, “the non-literary origins of the work show through in the telling.” You don’t say. And the last book, Riccardino, whose publication in September 2021 we celebrate now, is a story set long before Salvo and Antonia ever meet.

We’ll have more to say about Riccardino later. Suffice it to say it concerns the evolution of a case like none that Montalbano and his police colleagues have ever seen before.

And they’ve seen a lot. Montalbano’s fellow policemen are an idiosyncratic lot and, yes, they break his balls with regularity.

Chief among them are Sergeant Fazio, Montalbano’s right hand man, and Mimi Augello, Salvo’s deputy and friend. Both are smart investigators and great sounding-boards, happy to bounce ideas back and forth with Montalbano as they try to untangle cases. They both have flaws, of course. Fazio has a “records office complex,” a habit of reeling off far more information than Montalbano could ever want, and causing him to warn him many times, “If you start reading me his date and place of birth and mother’s and father’s names, I’ve going to take that piece of paper out of your hands, crumple it up into a ball, and make you eat it” (A Voice in the Night, 2016). He also has the annoying habit, when Montalbano asks him to do something, of replying, “Already taken care of,” which sends Salvo into a tizzy.

Mimi, for his part, is an excellent cop, but an inveterate womanizer. Even after he marries the lovely Beba (whose first child they name Salvo!), he still can’t help himself. “Mimi, if you don’t straighten yourself out, and fast,” Montalbano tells him, “one of these days some jealous husband is going to shoot you, and I’ll give him a hand fleeing justice” (The Pyramid of Mud, 2018). Beba tells Salvo in The Safety Net (2020) that just a year into their marriage, she knew Mimi was incorrigible, but she loves him anyway. That doesn’t prevent her from sending him to the hospital, though, with the dent of a heavy thrown ashtray on his forehead.

And that doesn’t stop Mimi from an occasional bout of sarcasm. When Montalbano reluctantly praises him for an action in The Overnight Kidnappers (2019), Mimi tells him to stop right there: “Otherwise the effort might be so tremendous you’ll end up with a hernia.” Another time, viewing Montalbano’s battered face, he makes the sign of the cross and raises his eyes to heaven.

“What’s the little comedy routine for?”

“I was saying a prayer of thanksgiving for whoever it was that gave you a black eye.”

“Stop being a wise guy and sit down.”

The other office colleague who must be singled out is Agatmo Catarella, a constant fount of garbled names, misunderstandings, and a unique Sicilian accent that the books’ sterling translator, Stephen Sartarelli, has fashioned into a kind of Bronx-Brooklyn-maybe-Cockney? patois. Catarella was originally hired because he was the distant relative of a powerful politician, and, for all his malapropism, paradoxically mans the switchboard because Montalbano figured he’d do the least damage there. The thing about Catarella, though, is, as exasperating as he is – everybody loves him. He’s like a little kid, good-hearted and enthusiastic (and surprisingly good with computers), and he can hardly contain himself when he gets praise, or Mimi asks his opinion, or Montalbano shares a sandwich with him. They’ve all become highly protective of Cat, and woe betide anyone who belittles him, even when the doors to their offices crash open (“My hand slipped!”) with his over-the-top urgency: “Ahh Chief, Chief! Jesus Christ, Chief! Jesus Christ and Mary and Joseph, Chief! I can’t hardly breathe, Chief!” (The Age of Doubt). To not have Catarella among them, “poissonally in poisson,” would diminish them all.

Not so with Montalbano’s commander, Commissioner Luca Bonetti-Alderighi: young, testy, often exasperated, always political, the Commissioner is an accomplished second-guesser, and only gives Montalbano free rein when he’s sure that if something goes wrong, it’ll be Montalbano who takes the fall. He’s constantly bypassing Salvo to give cases to his “specialists” or the latest head of his Flying Squad, all of whom come and go with dizzying speed and a singular lack of competence.

His fraud specialist falls victim to scams, his second-in-command gets mugged in Manhattan, his Flying Squad captain proclaims a victim of Kalashnikov fire to have been killed by “a dozen stab wounds inflicted in rapid succession” (Excursion to Tindari, 2005). Because he is “too superior a man to imagine that anyone would dare to make fun of him” (Riccardino, 2021), Salvo copes by doing exactly that, either by playing the bumpkin – “If he pretended to be utterly incapable of understanding the slightest thing, the Commissioner would leave him in peace” (“Seven Mondays,” Montalbano’s First Case and Other Stories) – waxing indignant – “You, Mr. Commissioner, actually believed such a groundless accusation? Ah, I feel so insulted and humiliated!” (The Potter’s Field) – or being effusively apologetic – “I’m terribly sorry, sir, but I can’t make it at nine….You see, Dr. Gruntz is coming all the way from Zurich….He’s coming straight to my house to perform a double Scrockson on me, the effects of which – as I’m sure you know – can last from three up to five hours” (The Dance of the Seagull, 2013).

One of those approaches is certain to be sufficient to get him out of Bonetti-Alderighi’s office – and free to investigate the case himself with his own men, but “underwater, with only our periscope showing” (Voice of the Violin, 2003). In that, he is both helped and hindered by what he calls the “clown caravan,” the three-ring circus of coroner, public prosecutor, and Forensics head (pre-Antonia) that must be called to every murder scene. The Forensics man, Dr. Arqua, is a Bonetti-Alderighi appointee, so you know the story there. He and Montalbano regard each other with mutual antipathy. The public prosecutor, Judge Tommaseo, drives “like a drunken dog,” crashing into trees, and the more salacious the crime, the more he enjoys it (“Any crime of passion, any killing related to infidelity or sex, was pure bliss for him,” August Heat).

Dr. Pasquano, the coroner, is the best of the bunch, because he’s truly competent, and Montalbano knows he’ll get real information from him – if, that is, Pasquano is in the right mood: “’What a colossal pain in the ass you are, Inspector! What the hell do you want?’ Pasquano began, with the gentle courtesy for which he was famous” The Potter’s Field). Montalbano doesn’t mind – the coroner is talking his language. Besides, he knows much of it is for show: “Pasquano was very keen on being known as an impossible man. Sometimes he took great pleasure in hamming it up just to maintain his reputation” (The Wings of the Sphinx).

All of the character descriptions make it sound like there’s a lot of humor in the books, and that is certainly the case. The crimes, though, are deadly serious, and sometimes shake Montalbano to his core.

A body found floating in the ocean leads to a ring trafficking in children (Rounding the Mark, 2003). A man shot at point blank range reveals a family history of incest (The Paper Moon). The erratic behavior of a seagull unfolds into a story of sadism, extortion, and chemical weaponry (Dance of the Seagull, 2013). A baffling rash of burglaries cloaks the deeds of a man driven mad by the need for revenge (Angelica’s Smile). A man found dead at a construction site exposes a massive collaboration of political corruption and the Mafia (Pyramid of Mud). The disappearance of a financial wizard, with a lot of Vigàta’s money, opens the curtain on a labyrinthine scam and a maelstrom of love, blackmail, betrayal, and obsession (The Smell of the Night).

Sometimes the cases start simple and quickly become complicated, demanding to be exposed. Other times, those complications reveal a human tragedy that Montalbano feels is better left to the participants. Two or three cases at once can interlock. Sometimes, major cases are put aside, so Montalbano can follow his own personal fascination, as when a weapons-smuggling investigation leads him to a cave, where lie the bodies of a man and a woman dead fifty years, watched over by a terra-cotta dog. For Montalbano, this is a much more interesting story – and opens up a dark secret of World War II Sicily.

And sometimes the resolutions the law supplies simply aren’t enough. In Game of Mirrors, the murderer is untouchable, until a television interview by Montalbano sets the victim’s father on an appropriately vengeful course. In The Snack Thief, Montalbano blackmails an unscrupulous Secret Service agent into doing the right thing. In A Voice in the Night (2016), leaked information results in the suicide of one murderous Mafia-connected politician and the public exposure of another: “Montalbano thought that, when all was said and done, things could not have gone any better.”

That doesn’t mean he’s happy about it. Montalbano is constantly disgusted by the “circus of corrupters and corrupted, extortionists and grifters, bribe-takers, liars, thieves, and perjurers” (The Terra-Cotta Dog, 2002) that seem to run every institution. “One always ended up caught in dangerous webs of relations, collusions between the Mafia and politicians, the Mafia and entrepreneurs, politicians and banks, money-launderers and loan sharks. What an obscene ballet! What a petrified forest of corruption, fraud, rackets, villains, business!” (August Heat).

Sometimes it amuses him, a little bit: “He changed the channel. There was a cardinal talking about the sacred institution of the family. In the first row of the audience were an array of politicians, two of whom had been divorced, another who was living with a minor after leaving his wife and three children, a fourth who maintained an official family and two unofficial families, and a fifth who had never married because, as was well-known, he didn’t like women. All nodded gravely in agreement with the cardinal’s words” (The Potter’s Field),

However, some of the time, it’s all too much, especially when it also reflects his own police force. After a violent police raid on peaceful protestors in Genoa, he is left “unable to think, shaking with rage and shame.” “Do you realize what happened, Livia?” he cries over the phone. “The police attacking the school and planting false evidence weren’t a bunch of stupid, violent beat-cops; they were commissioners and vice-commissioners, inspectors and captains and other paragons of virtue” (Rounding the Mark). And to Mimi, he announces his intention to quit:

“The rot is inside us.”

“Did you just find that out today? With all the books you’ve read? If you want to quit, go ahead and quit. But not right now. Quit because you’re tired, because you’ve reached the age limit, because your hemorrhoids hurt, because your brain can’t function anymore, but don’t quit now.”

“And why not?”

“Because it would be an insult.”

“An insult to whom?”

“To me, for one – and I may be a womanizer, but I’m a decent man. To Catarella, who’s an angel. To Fazio, who’s a classy guy. To everybody who works for the Vigàta Police. To Commissioner Bonetti-Alderighi, who’s a pain in the ass and a formalist, but deep down is a good person. To all your colleagues who admire you and are your friends. To the great majority of people who work for the police and have nothing to do with the handful of rogues at the top and the bottom of the totem pole. You’re slamming the door in all of our faces. Think about it. See you later.”

Montalbano does, and stays – but it wears him down. As the books go on, he is increasingly conscious of the passing years, of his growing age, of his maybe losing a step. He berates himself for it – “Let’s not start again with this pain-in-the-ass stuff about old age setting in! You’re just fabricating a convenient excuse!” (Game of Mirrors) – but he can’t help wondering if his bouts of besottedness would have happened otherwise – “If you hadn’t been fifty-five years old, would you have been able to say no? Not to Adriana, but to yourself? And the answer could only be: Yes” (August Heat).

A man who had always scorned taking notes, he now finds himself resorting to other stratagems to keep everything straight. He writes letters to himself, summarizing cases. He debates himself, Montalbano One and Montalbano Two. He has dreams, whose meaning he can’t comprehend until they start playing out in real life.

How much longer can he keep it up, he wonders? And so we come to Riccardino.

In 2004-2005, Camilleri wrote a novel, sent it to his publisher, and told him to lock it in a desk drawer. “This is the last Montalbano,” he said. “Leave it there, and the moment I don’t feel like writing Montalbano anymore, or I get bored, I will tell you, ‘publish that last book.’” He partially revised it in 2016, but he never got bored. Now, two years after his death, this is the end of the series, the way he meant it to be.

At five o’clock in the morning, Montalbano is woken up by the phone: “Riccardino here! Did you forget that we had an appointment? We’re all here already, outside the Aurora, and you’re the only one missing!” It’s obviously a wrong number, but he lies, tells the man he’ll be there, and falls back into bed.

One hour later, Fazio calls to tell him there’s a dead body at the Aurora. It’s a man named Ricardo. He and three boyhood friends, all closely interconnected, were about to head off on a hike, when a motorcyclist sped by and shot Ricardo. Or at least that’s their story. The more Montalbano probes, the more ambiguous their relationships become, the more complicated, and then, when the Bishop of Montelusa enters the picture, more complicated yet.

That is not Montalbano’s only problem, however. He keeps getting mistaken for someone else, an actor who plays him in a popular television series. And he keeps getting calls from a man with a “smoke-shredded voice,” who says he’s the Author, berating him for straying off-course.

This moment is presaged by a short story that Camilleri wrote earlier, called “Montalbano Says No,” in which Salvo, upset by the extreme violence of the case in which he’s becoming involved, calls up a seventyish man at a typewriter and refuses to continue with the story any longer.

This time, the Author is not taking any guff, however. “It’s me who informs you, and I don’t know why you insist on thinking that it’s you who informs me.” He says Montalbano is too wrapped up in his television alter ego. “This constant comparison is muddling your thoughts. And as a result, you’re damaging my story as well. Your investigations are not what they used to be. You’re too often uncertain, vague, contradictory, and even scatterbrained. You keep invoking the problem of imminent old age, but I know perfectly well that it’s just an excuse for covering your increasing indecision. Can’t you see that you’re presently unwilling, in this Riccardino story, to set the investigation on a specific, well-defined path? I offer you a lead, and you start joking around, and as a result I find myself in a pickle.”

Accused of not knowing how to lose, Montalbano responds, “You’re wrong. I do know how. But when it happens, it pisses me off.”

You do not want to piss Montalbano off. Where this all goes is a surprise, a delight, a deeply affecting meditation on free will and impermanence – and as satisfying a conclusion to a long-running series as you could possibly want.

***

Here’s the startling fact about that series, though: it didn’t even begin until the author was 69 years old.

Born in 1925 in Porto Empedocle, Sicily – the inspiration for Vigàta – Camilleri spent most of his life as a stage and television director, screenwriter, producer, and teacher. He was known especially for his theatrical productions of Beckett and Pirandello, a fellow native of Porto Empedocle and whom his parents knew, and for cultural programs on RAI, the Italian state broadcasting corporation, including a thirty-episode television series based on Georges Simenon’s Maigret.

He got into it all when he began studying film direction at the Academy of Dramatic Arts from 1948 to 1950, but left early when he got the chance to practice it in real life. Decades later, he would return to the Academy, where he’d been offered the chair of Film Direction, and taught there for 23 years.

His first attempt at a novel was in 1978, with The Way Things Go, and then again with 1980’s A Thread of Smoke, but neither made any impact. Finally, he hit it right with 1992’s The Hunting Season, a bestselling novel of sex and adventure set in 1880s Vigàta. This was more like it! And then he got stuck.

The book he was working on just wouldn’t cooperate. “I couldn’t organize it the way I wanted. I had not found the key to structure it, and decided that the best solution was to set it aside and write something else. And I said to myself: What can I write? The way I used to write novels was to start with the very first thing that struck me about a subject. It was not methodical: the first thing I wrote would never be the first chapter, but maybe it would become the fourth or fifth chapter. Then I said: but you can write a novel from the first to last chapter with a perfect order of logic. I saw the form of a thriller as a cage that does not allow you to escape. Everything has to be in a certain place.” Besides, social commentary was always his aim, and he knew he could “smuggle” that into a detective novel, as well.

When it came to creating his hero, Camilleri had two influences. One was the Spanish writer Manuel Vazquez Montalban, who wrote a series he loved about an investigator named Pepe Carvalho. Camilleri christened his inspector Montalbano in tribute. The other influence was his father, who worked for the Italian Coast Guard and always had a certain disregard for authority.

“Let me tell you a personal story to give you an idea of how much of my father has passed on to Montalbano,” he said. “My father was a real Fascist, one of the true believers. Then one day in 1938, a school friend of mine called Marcello Pera came to me and said goodbye. He said, ‘Tomorrow I’m not coming to school.’ I said, ‘Why not, Marcello?’ ‘Because I’m a Jew.’ What it meant to be Jewish hit me like a bolt from the blue.

“So I went home to my supper and I said to my dad, ‘You know my friend Marcello Pera? He can’t come to school any more because he’s Jewish.’ My father hit the roof, saying, ‘That bastard!,’ referring to Mussolini. “The Jews are like us!’ he roared.

“That was my father. And I’ve always tried to make Montalbano critical about the behavior and orders of his bosses, the imbecility of power.”

The Shape of Water was an instant hit. Its first print run of 100,000 copies sold out, another 80,000 was printed, and then 20,000 more – all in the first five days. The Terra-Cotta Dog did much the same. Camilleri had been intending to move on to something else after that, but “I kept receiving calls from my publisher bombarding me with, ‘Oh no, you must give me another Montalbano.”

And then if that weren’t enough, in 1999, only four books into the series, the RAI television series, Il Commissario Montalbano, hit the air. It became an instant sensation…and has been on the air ever since, even inspiring a second, briefer series, The Young Montalbano. It made a star of the actor portraying Montalbano, Luca Zingaretti, and has been broadcast all over the world, including the BBC in the UK and MHz Choice in the U.S.

Camilleri himself became omnipresent on Italian radio and TV, expounding on political, social, and cultural matters, his voice – hoarse, raspy, with a strong Sicilian accent – so distinctive that one Italian comedian made a nice living imitating him on the radio.

Towards the end of his life, he became blind, and from The Other End of the Line onward, had to dictate his books to his assistant, Valentina Alferj. He says it made his books even better. In all, he wrote more than 100 books during his lifetime: fiction, nonfiction, historicals, crime.

He died in July 2019, at the age of 93, after a month hospitalized with complications of a broken thigh bone and heart problems. Among his honors: the 2012 Crime Writers’ Association International Dagger for The Potter’s Field; the title of Grand Officer in the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic; and the Asteroid 204816 Andreacamilleri, discovered by an Italian astronomer and named after him in 2007.

The two honors that might have tickled him the most, though: In 2003, the mayor of Porto Empedocle, the real-life Vigàta, officially changed the name of the town…to Porto Empedocle Vigàta. The decision was reversed in 2009, but still. And a statue of Salvo Montalbano was erected in the middle of the town, near another statue – of Luigi Pirandello.

Laughing, Camilleri remarked, “Pirandello, in his statue, has his fingers pointing like this,” making his hand into a pretend gun. “And, because of where the Montalbano statue is, it’s as if he’s pointing and saying, ‘What are you doing here?’”

“If I could,” he said in one of his last appearances, “I would like to end my career sitting in the middle of the square, telling stories, and at the end, walk among the audience with my hat in my hand.”

It feels like he got his wish.

___________________________________

The Essential Camilleri

___________________________________

With any prolific author, readers are likely to have their own particular favorites, which may not be the same as anyone else’s. Your list is likely to be just as good as mine – but here are the ones I recommend.

Rounding the Mark (2006)

Montalbano is at the Vigàta docks and witnesses the nightly tragedy as new groups of desperate illegal immigrants arrive:

“Every time the same scenes of tragedy, tears, and sorrow. There were women giving birth, children lost in the confusion, people who’d lost their wits or fallen ill during endless journeys outside on the deck, exposed to the wind and the rain, and they all needed help. When they disembarked, the fresh sea air wasn’t enough to dispel the unbearable stench they carried with them, which was a smell not of unwashed bodies but of fear, anguish, and suffering, of despair that had reached the point beyond which lies only the hope of death.”

One of these immigrants is a six-year-old boy, and when he runs away in fear, his mother calling for him, Montalbano kindly fetches the boy and reunites them. Or did he? Something feels off about the scene, he can’t quite put his finger on it, but when the boy is later reported dead, he has a sickening feeling in the pit of his stomach: “The valiant, brilliant Inspector Salvo Montalbano had taken that boy by his little hand and, ever willing to help, turned him over to his executioner.”

So begins a harrowing adventure, as Montalbano goes on the hunt for men engaged in what turns out to be a very specific import/export commodity – children, bought and sold for organ transplants, pedophilia, and professional begging schemes. Soon, it will become entangled with another horror to which he is all too close, when, swimming in the ocean outside his house, he bumps into a body, its wrists and ankles bearing he marks of having been tied with iron wire. It has clearly been in the water for a long time. Or has it? The answers to all his questions will come in a hair-raising midnight chase, alone, to where a killer awaits – and another enemy as well, one Montalbano could never have predicted.

Strong stuff.

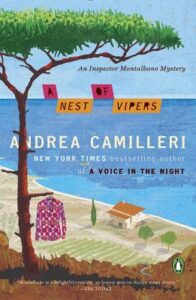

A Nest of Vipers (2017)

It was one thing to send the killer of a good man to jail, it was something else entirely to put away someone who had killed a stinking scoundrel.

The stinking scoundrel in question is an older man named Cosimo Barletta, dead of a single shot at the base of his skull. Barletta was many things, all of them bad: a loan shark, a blackmailer, a thoroughly unscrupulous businessman, a womanizer with a steady stream of young girls in their twenties.

“Would you believe me if I tell you that I’d heard he’d been killed, I started jumping for joy?” says one of those girls. “I would spit on his corpse if I could.”

Montalbano knows this case is going to be a headache, because it seems that just about everyone the man ever knew would have been delighted to fire that shot. The more he digs, though, the more he suspects the answer lies closer to home, with the two adult children who both loved and loathed him. They are both harboring secrets, but the truth, when it finally comes out, will hit like a thurderclap.

Barletta was more than a stinking scoundrel. He was a monster. And he isn’t the only monster Montalbano will uncover.

Every Montalbano novel carries an Author’s Note from Camilleri with the standard legal disclaimer that all the characters and incidents in the book are made up. For this one he also added: “I do hope nobody will claim to recognize him- or herself in this story.” No kidding.

The Safety Net (2020)

In his youth, in 1968, he, too, had cried out that telling the truth was a revolutionary act, that the truth must always be told.

No, no…For some time now he’d known that the truth was sometimes better kept under wraps, in the darkest darkness, without so much as the glow of a lighted match.

A suicide that is not a suicide.

A school shooting that is not a school shooting.

And no one must ever know what really happened.

The filming of a Swedish TV series set in 1950s Vigàta is underway, and the producers’ request for vintage pictures and home movies to help set the atmosphere has been met with an enthusiastic outpouring. One local’s attic discovery has particularly intrigued Montalbano – a series of movies from 1958 to 1963 set always on March 27th, always at 10:25 a.m., always of the same outside wall of a country house.

Eternally “attracted to the intricate muddle that is a man’s soul,” Montalbano starts poking around, only to be interrupted by a much more urgent situation: two masked men have invaded a middle school classroom, fired in the air, and then engaged in a shootout with Mimi, who happened to be there to check on his son.

Nobody was hurt, thankfully, but what were they doing there? What was their purpose? Montalbano digs in, and finds himself set adrift on the unfamiliar seas of teenage social media, where a hundred different things seem to be going on all at the same time, and the waters are very, very deep. Everything is laid bare, and yet nothing is what it seems – a fact that reverberates even more when he goes back to look at those old home movies and the country house wall.

No, no…sometimes the truth is better not known.

___________________________________

Book Bonus

___________________________________

As mentioned above, Camilleri wrote a lot of other fiction, mostly historical dramas and comedies such as The Hunting Season, which is available in translation from Penguin, as is The Brewer of Preston, set in 1870s Vigàta (and which is, incidentally, the book Camilleri was stuck on when he detoured to write the first Montalbano). Europa Editions has also brought out some books written toward the end of his life, in which Camilleri “brought his trademark wit and noir pacing” to a series of novels retelling key, forgotten moments in Sicilian history. Translated, like the Montalbanos, by Stephen Sartarelli, they include The Sect of Angels, The Sacco Gang, and The Revolution of the Moon.

Of more interest to Montalbano fans will be Camilleri’s two collections of stories, Montalbano’s First Case and Other Stories and Death At Sea: Montalbano’s Early Cases (2018), both of them culled from four story collections published in Italian. There are 29 stories in total, all featuring Montalbano, some short, some long, all as much interested in exploring Sicilian characters, settings, and situations as in the specific crimes involved; and “almost all collected here to answer questions I had, or to settle bets I had made with myself, or to treat narrative problems I had set for myself.”

“Montalbano’s First Case” has already been referenced at the beginning of this piece, and is essential for any Salvo fan, as is “Montalbano Says No,” but they’re all wonderful reading, showing a master at work, setting tasks for himself, scratching itches, demonstrating the wit, humanity, and capacity for chilling observations that fill all his novels.

___________________________________

Sicily Bonus

___________________________________

“There is no Sicilian woman alive, of any class, aristocrat or peasant, who, after here fiftieth birthday, isn’t always expecting the worst. What kind of worst? Any, so long as it’s the worst.”

- The Snack Thief

“’Where’d you get this information>’

“’From a cousin of the uncle of a cousin of mine, who I found out works at the hospital.’

“Family relatives, even those so distant that they would no longer be considered such in any other part of Italy, were often, in Sicily, the only way to obtain information, expedite a bureaucratic procedure, find the whereabouts of a missing person, land a job for an unemployed son, pay less taxes, get free tickets to movies, and so many other things that it was probably safer not to reveal to people who were not family.”

- The Track of Sand (2010)

“’You know how things go in Italy, don’t you? Everything that happens up north – Fascism, liberation, industrialization – takes a long time to reach us. Like a long, lazy wave.’”

- The Patience of the Spider (2004)

“’Nobody can identify, nobody gives chase.’ ‘What else can you expect on this fine island of ours? You can see, but you cannot identify. You’re present, but can’t say anything definite. You saw, but only vaguely, because you forgot your glasses at the time….Yessir, I was there, but I was unable to give chase because one of my shoes was untied. Yessir, I saw everything, but I couldn’t intervene because I suffer from rheumatism.”

- Riccardino

“’Everybody knows everything, but nobody wants to tell us.’

“’A typical residential building in Sicily.”

- The Sicilian Method

___________________________________

Sicilian Bonus

___________________________________

The style of the Montalbano books is unique, in that they were all written in a combination of Italian, Sicilian, and Sicilianized Italian. One of Stephen Sartarelli’s invaluable endnotes for The Terra-Cotta Dog comments, “Many uneducated Sicilians, even in this day of mass media and standardized speech, can only speak the local dialect and tend to struggle with proper Italian. Oftentimes what comes out when they attempt to use the national language is a linguistic jumble that is neither fish nor fowl,” or what Camilleri refers to in The Shape of Water as an “incomprehensible dialect consisting not so much of words as of silences, indecipherable movements of the eyebrows, imperceptible puckerings of the facial wrinkles.”

It is a forest of pungent expressions and sayings, however, and here are just a few of them from the Montalbano books:

Fa u fissa pi nun iri a la Guerra. “Play the fool to avoid going to war,” meaning “to play dumb.”

All’ annigatu, Petri di ‘incoddru. “Rocks on a drowned man’s back,” or “an unrelenting string of bad breaks that drag a poor stiff down.”

Nottata persa e figlia femmina. “A night lost, and it’s a girl,” meaning “A whole night in labor, and not a son” or “What a lot of wasted effort.”

Savuta ‘u trunzu e va ‘n culu all’ortolano. “The shears fly into the air and end up in the gardener’s asshole,” or “it’s the little people who always bear the brunt of misfortune.”

___________________________________

Old-Mafia-Semiology Bonus

___________________________________

“This murder had been committed, or ordered – which amounted to the same thing – by someone who still operated in observance of the rules of the ‘old’ Mafia,

“Why?

“The answer was simple: Because the new Mafia fired their guns pell-mell and in every direction, at old folks and kids, wherever and whenever, and never deigned to give a reason or explanation for what they did.

“With the old Mafia, it was different. They explained, informed, and clarified. Not aloud, of course, or in print. No. But through signs.

“The old Mafia were experts in semiology, the science of signs used to communicate.

“Murdered with a thorny branch of prickly pear placed on the body?

“We did it because he pricked us one too many times with his thorns and troubles.

“Murdered with both hands cut off?

“We did it because we caught him with his hands in the cookie jar.

“Murdered with his balls shoved into his mouth?

“We did it because he was fucking someone he shouldn’t have been.

“Murdered with his shoes on his chest?

“We did because he wanted to run away.

“Murdered with both eyes gouged out?

“We did it because he refused to see the obvious.

“Murdered with all his teeth pulled out?

“We did it because he ate too much.

“And so on merrily in this fashion.”

- The Potter’s Field

___________________________________

“Take That” Bonus

___________________________________

Camilleri was a fan of many mystery characters, and references to Maigret, Sjöwall and Wahlöö’s Martin Beck, and even Lieutenant Columbo pop up freely. He was also considerably annoyed by those who looked down their noses at the mystery genre or considered his own writing too tame. In his introduction to Montalbano’s First Case and Other Stories, he notes his antipathy to “the so-called cannibals of contemporary Italian fiction, who scorned my writing for what, they accused, was ‘feel-goodism,’ and I decided to respond.” That response was “Montalbano Says No,” in which the inspector refuses to go along with the savagely brutal plotline devised by the author (obviously a proponent of the “cannibals”).

Camilleri has other things to say, too:

“He sat outside until eleven o’clock, reading a good detective novel by two Swedish authors who were husband and wife in which there wasn’t a page without a ferocious and justified attack on social democracy and the government. In his mind Montalbano dedicated the book to all those who did not deign to read mystery novels because, in their opinion, they were only entertaining puzzles.”

- August Heat

[A snob propounds the virtues of what he calls the “para-detective genre” to Montalbano:]

“’And what’s that?’

“’It means the works seem to have mystery plots, but in reality are profound investigations into the soul of contemporary man.’

“Montalbano reflected that there was no such thing as a good cop who wasn’t able to dig deep into the human soul.”

- The Sicilian Method

“’You’ve certainly got a lively imagination,’ Mimi commented after thinking over the inspector’s reconstruction of events. ‘When you retire you could start writing novels.’

“I would definitely write mysteries. But it’s not worth the trouble.’

“’Why do you say that?’

“’Because certain critics and professors, or would-be critics and professors, consider mystery novels a minor genre. And, in fact, in histories of literature they’re never even mentioned.’

“’Why the hell do you care?…Just write them and be content with that.’”

- Excursion to Tindari

___________________________________

“Speaking-of-Columbo” Bonus…

___________________________________

Camilleri’s largesse did not necessarily extend to American film and TV, however.

“He kicked open the bathroom door and then the others one by one, feeling ridiculously like the hero of an American TV program.”

- The Shape of Water

“He couldn’t stand the sallies of cheap psychoanalysis that Livia all too often liked to indulge in – the kind of stuff you got in American movies where, say, some guy kills fifty-two people and then we find out that it’s because one day, when he was a little kid, the serial killer’s father wouldn’t let him eat strawberry jam.”

- The Smell of the Night

“Chief, if you know how to do it, you can turn a common alarm clock into a timing device. I know you see it all the time in American movies, but that doesn’t mean it’s not true.”

- Treasure Hunt

[Mimi discussing an American who’d just had her purse snatched]:

“’I said that we, as policemen, weren’t really in a position to do anything about it, and she should turn to the consulate for help.’

“’There’s an American consulate in Vigàta?’

“’I don’t know. But there probably is. Maybe up on some desolate cliff overlooking the sea.’

“’Mimi, could it be that you’ve become just a wee bit anti-American?’

“’Me?! Come on! I’m the only one on the entire police force who chews original U.S.-brand chewing gum! And I smoke Camels! And drink Coca-Cola! And I haven’t missed a single Schwarzenegger movie! What the hell is wrong with you?’”

- The Cook of the Halcyon