William Taffer shot from his berth. Loud noises above his head—“like a beating or hammering,” he recalled—had jarred him awake. It was three in the morning. He was climbing toward the deck of the cargo vessel Flowery Land to investigate when he saw sailors armed with clubs pummeling someone who was lying facedown at the top of the ladder. One of the assailants spotted him as he emerged from the hatch and struck him on the side of the head. Dazed, the second mate retreated below deck and called for the captain. There was no response. Rushing to the main cabin, he discovered the body of Captain John Smith lying in a pool of blood. He had been stabbed to death. Taffer locked himself in his cabin and waited, listening for footsteps. The mutineers, he was certain, would come for him next.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s true crime tale of the 1863 mutiny on board the British cargo ship Flowery Land was published in the Philadelphia Inquirer and other major American newspapers in 1899. (Philadelphia Inquirer, April 2, 1899)

Arthur Conan Doyle’s true crime tale of the 1863 mutiny on board the British cargo ship Flowery Land was published in the Philadelphia Inquirer and other major American newspapers in 1899. (Philadelphia Inquirer, April 2, 1899)

He would be the only ship’s officer to survive the brutal takeover of the Flowery Land in the mid-Atlantic on the morning of September 10, 1863. By the time he awoke, a band of Filipino crewmen had ambushed and beaten the first mate, John Carswell, then callously thrown him overboard while he was still alive. The captain had been next and the man Taffer had seen being clubbed to death was the captain’s brother, George, who was on board as a passenger. More men would die before the crew made landfall in South America and Taffer escaped to tell his tale.

“Dreadful Mutiny at Sea,” proclaimed a headline in the Liverpool Mercury when news of the bloody uprising reached England almost two months later. By then, the surviving crew members were aboard a Royal Navy warship and on their way to London. Eight were slated to stand trial for murder in the Old Bailey, where a jury would be asked to decide who had taken part in the killings. And the mutineers’ motives would soon become clear. Only one mystery surrounds the tragic tale of the Flowery Land, making it stand out among the many horrifying episodes of mutiny and piracy during the Age of Sail. Why did Arthur Conan Doyle, whose master detective Sherlock Holmes would have made short work of such an open-and-shut case, choose the mutiny as one of his few forays into the writing of true crime?

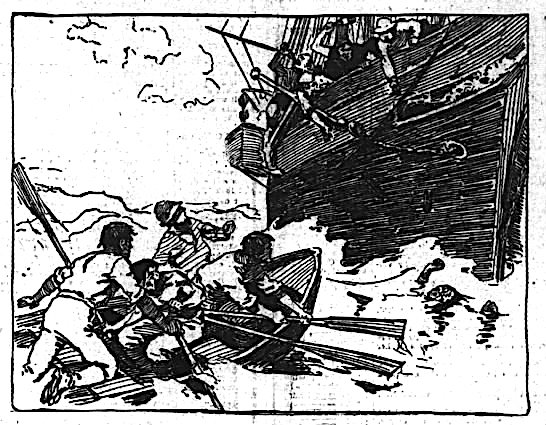

The mutineers and surviving crewmen cast off in small boats before the ship was scuttled off the coast of Argentina, in an illustration that accompanied Conan Doyle’s story. (Nashville American, March 19, 1899)

The mutineers and surviving crewmen cast off in small boats before the ship was scuttled off the coast of Argentina, in an illustration that accompanied Conan Doyle’s story. (Nashville American, March 19, 1899)

The Flowery Land—the ship’s name was a common nineteenth-century term for China—sailed from London on July 28, 1863, bound for Singapore with a cargo of iron pipes, champagne and other wines, and bales of cotton. The crew was drawn from an array of countries—England, Spain, France, Norway, Greece, China, present-day Indonesia—but the largest contingent was a half-dozen Filipinos. These “Manila men,” as they were known, spoke little English. The most fluent among them, who called himself John Lyons, acted as a go-between, interpreting the orders for the rest, who acknowledged him as their leader.

Conditions on board soon spiraled into violence. The Manila men demanded more food and complained that their water ration, three buckets a day, was not enough. “Drink salt water, then,” was Captain Smith’s alleged response. Unable to communicate with many of his crew, the captain slapped or punched the men—“sons of bitches,” he called them—who botched tasks or seemed to defy his authority. “You are come aboard my ship as able seamen, and you cannot do your work,” he shouted during one tirade. The first mate, Carswell, could be just as cruel and violent. “He was a strict man,” Taffer acknowledged, “but he had to be strict—he wanted his work done.”

Two incidents about five weeks into the voyage, after the ship reached the coast of Africa and turned west to cross the Atlantic, may have touched off the mutiny. George Carlos, a Spaniard on the same watch as the Manila men, said he was too sick to work. Carswell, convinced he was faking illness, hauled him from his bunk and lashed him to the mast as punishment. The captain, in a rare display of kindness, intervened and directed that the man be sent back to his berth and given medicine. A few days later, when Carlos was scuffling with another crewman, Carswell intervened and punched him. The obstinate Spaniard and the disgruntled Manila men, who shared a common language, were now united in their hatred of the ship’s officers.

After Carswell and the Smith brothers were murdered, Carlos and the Manila men gathered outside Taffer’s cabin. The second mate emerged at their command and discovered he would be spared; he was the only one left who could navigate the ship. Their new destination was the River Plate in northern Argentina. “A good country,” Carlos told him, with “plenty of Spanish people there.” Taffer was allowed to wrap the captain’s body in canvas before it was tossed overboard, as a mark of respect. “There goes the captain,” one of the Manila men muttered in Spanish as the bundle sank. “He will never more call us sons of bitches.”

Tense days followed as men who had not taken part in the uprising endured threats and menacing looks. Crates of champagne were broken open and soon empty bottles and drunken men littered the deck. The captain’s money and belongings were divided seventeen ways, to make everyone left on board guilty at least of theft. Taffer expected to die the moment they sighted land but John Lyons, who seemed to be in command of the mutineers, became his protector. “He showed every anxiety,” the second mate recalled, “to save my life.” When they reached the Argentine coast in early October, the carpenter was ordered to bore holes in the hull to scuttle the ship. There was a final round of killings as fourteen men cast off in small boats. The steward and a cabin boy were murdered; the cook was left on board and drowned when the ship sank.

The sailors came ashore with a cover story—their ship had foundered far offshore and they had been adrift for days. Taffer, however, escaped and reported what had really happened as soon as he found someone who could speak English. Argentinian authorities quickly rounded up the rest of the crew. Taffer and other survivors identified the mutineers when eight crewmen charged with murder stood trial in February 1864. Defense lawyers, unable to dispute the eyewitness accounts, suggested the Flowery Land might not be a British vessel, rendering the crimes beyond the jurisdiction of British law; it turned out the owner was Scottish, allowing the prosecution to proceed. Six Manila men and a seaman from the Middle East were convicted; Lyons, who had saved Taffer’s life, was among the five men hanged outside London’s Newgate Prison as a raucous crowd looked on. George Carlos was acquitted of murder but sentenced to ten years in prison for his role in sinking the ship. “The crime was heinous,” acknowledged London’s Daily Telegraph, but Filipinos worked on hundreds of vessels without endangering their masters. The Flowery Land’s abusive officers appeared to have goaded the Manila men—the “poor sweepings of maritime places”—to kill.

Conan Doyle’s experiences as a ship’s doctor on two voyages in the early 1880s likely piqued his interest in the Flowery Land mutiny. (Author collection)

Conan Doyle’s experiences as a ship’s doctor on two voyages in the early 1880s likely piqued his interest in the Flowery Land mutiny. (Author collection)

Arthur Conan Doyle’s 3,900-word feature on the mutiny was published in at least a half-dozen major American papers, including the Atlanta Constitution and San Francisco Call, in March and April 1899. The story was little known in the United States, where not even a bloody tale of mutiny and murder had attracted much press attention in the midst of the carnage of the Civil War.

Conan Doyle’s account was accurate—he appears to have relied on British newspaper accounts and may have consulted the trial transcript—but began with an imagined conversation between the captain and the first mate before they sailed from London. Carswell supposedly warned that the unruly crew will “need thrashing into shape,” and it was safe to assume the mate said something along those lines. Conan Doyle’s description of the captain, however, strayed from fact into fiction. He was “a jovial, genial soul,” he claimed, “with good humour shining from his red, weather-stained face.” It was as if he feared it would taint the honor of the Empire for readers to learn the truth, that the commander of a British vessel could be so cruel. And when it came to describing the Manila men, Doyle succumbed to the racist stereotypes and attitudes of his times. They were dangerous, untrustworthy, and even looked evil, with their “flat Tartar noses, small eyes, low brutish foreheads, and lank, black hair.” Their execution, he wrote, was a “fitting consummation” to a “monstrous” crime.

What drew him to the story? In 1899 Conan Doyle was taking a sabbatical from Sherlock Holmes, after killing him off (along with arch enemy Moriarty) in “The Adventure of the Final Problem,” published in 1893. Holmes would not reappear until The Hound of the Baskervilles was serialized in 1901. In the years between he wrote the Napoleonic Era adventures of Brigadier Gerard and began to dabble in true crime. He published accounts of three other murder cases in the Strand Magazine during 1901 and would later undertake his well-known investigations of the wrongful convictions of George Edalji and Oscar Slater.

Conan Doyle would have found it hard to resist a crime committed at sea. Between 1880 and 1882, at the start of his medical career, he had served as ship’s doctor aboard a whaling vessel in the Arctic and on a steamer that cruised the west coast of Africa. He remembered the voyages as “the first real outstanding adventure in my life.” He knew ships and he knew the men who sailed them; the mate on the whaling expedition was, like Carswell of the Flowery Land, “a very hot-blooded man” easily provoked “to a frenzy.” Sea stories featured in Conan Doyle’s fiction, from the multiple adventures of pirate captain John Sharkey to an early ghost-ship tale, “The Captain of the Pole-Star.”

Something else may have attracted him to the Flowery Land mutiny. Conan Doyle was a law-and-order man who unleashed his Great Detective on fictional evildoers like an avenging angel. “I am the last court of appeal,” the last hope for those seeking justice, Holmes declared in one of his early adventures, “The Five Orange Pips.” The capture, conviction, and execution of the mutineers was a warning to real-world criminals; time and distance offered little protection from exposure and punishment. “No more striking example could be given,” in Conan Doyle’s opinion, “of the long arm and steel hand of the British law.”

___________________________________

Dean Jobb’s next book recreates the crimes of Victorian era serial killer Dr. Thomas Neill Cream, who preyed on women in England, the U.S. and Canada and became known as London’s feared Lambeth Poisoner (coming in July 2021 from Algonquin Books). He teaches nonfiction writing at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Sources:

Jack Tracy, ed., Strange Studies from Life and Other Narratives: The Complete True Crime Writings of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Gaslight Publications, 1988); “Trial of John Lyons et al. For Murder, February 1, 1864,” The Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674-1913 (www.oldbaileyonline.org); “The Execution of the ‘Flowery Land’ Pirates,” Daily Telegraph (London), February 23, 1864; The Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia (www.arthur-conan-doyle.com); Andrew Lycett, The Man Who Created Sherlock Holmes: The Life and Times of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Free Press, 2007); Arthur Conan Doyle, Memories and Adventures and Western Wanderings (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009).