Documenting a crime—never a simple task whether for evidence, publicity or posterity—requires a balance of science and art. In New York, it also takes a bit of gusto.

In 1863, a burly Irish immigrant named Thomas Byrne, already a war veteran and an experienced firefighter at 21, was inducted into the service of the NYPD and quickly rose through the ranks to a captaincy. By 38 he was heading up the Detective Bureau, where he cultivated a flair for theatrics. Every morning, at Byrne’s instruction, detectives would gather round with coffee and notepads while the prior evening’s arrests were escorted through the room and asked to strike a pose. It was called the Mulberry Street Morning Parade, the idea being that the detectives might note the salient features of the men on display and figure them for other crimes. It had a whiff of science and bolstered the bureau’s turn toward professionalism.

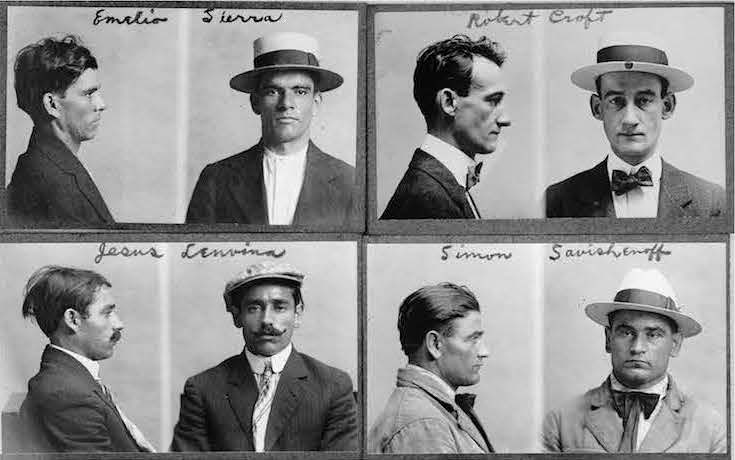

Encouraged, Byrne published his first edition of Professional Criminals of America, an encyclopedia of convicted criminals, which had the dual function of trumpeting the department’s successes and allowing the public to get in on the fun of keeping tabs on the city’s underclass. Byrne also began assembling his famous “Rogues’ Gallery”—a collection of photographs, identifying features and modus operandi for the city’s known and suspected criminals. The Pinkertons had been using a similar system for decades, but Byrne’s implementation in the nation’s largest city won him high marks as an innovator. He was, for a time, the most celebrated cop in America, a tabloid hero, right up until the moment Teddy Roosevelt took over as commissioner and forced him out on suspicion of corruption.

In the end, introducing photography into the NYPD may have been Byrne’s most lasting achievement. But it was another lawman, a clerk in the Prefecture of Police in Paris, France, who would bring the discipline into the 20th century. Alphonse Bertillon, the son of a statistician, had a yen for data. In his free time, he visited prisons to measure the anatomy of France’s criminals. Eventually, he developed a system for identification. He measured handwriting, too, and offered “expert” testimony in the notorious case against Alfred Dreyfus. Although some of Bertillon’s techniques and theories have fallen into disrepute, he’s credited with standardizing two major advances still in use today: the mug shot and the crime scene photograph.

The mug shot was a humdrum but reliable tool for keeping track of suspects and arrests. The crime scene photograph, on the other hand, required more finesse. Under Bertillon’s supervision, camera-trained detectives were dispatched to crime scenes, especially murders, with what was, essentially, an aesthetic mandate: get a ground-level shot of the body, then one more—the overhead shot that Bertillon called “l’oeil divin,” and which came to be known in English as the “God’s Eye View.”

Within a decade, Bertillon’s system was the state-of-the-art for police forces across Europe and the US. In New York, detective squads began carrying a specialist familiar with the technology. In 1934, under the supervision of police commissioner “General” John F. O’Ryan and his advisor, Dr. Harry Soderman—a Swedish forensics expert in the mold of Sherlock Holmes—the NYPD set up its first crime lab, featuring a dark room, archives, and skilled technicians.

The images developed there were used for identification, scene preservation, and, as courts grew comfortable with the idea, evidence in criminal prosecutions. After a case was closed or deemed sufficiently cold, the photographs were supposed to be destroyed. The vast majority of them were, but a few years ago, during renovations at 1 Police Plaza, a forgotten stash of glass negative plates, some dating back a hundred years, was found in basement storage. With a grant from the NEH, New York City’s Department of Records was able to digitize over 30,000 of the images and make them available for public viewing and research. Regarded without context or in too large a dose, the photographs are a macabre, haunting vision of the city. Given a little curating, they’re still macabre, still haunting, but not entirely out of place on your coffee table.

*

Murder in the City (St. Martin’s/Thomas Dunne)—a new book from Wilfried Kaute, a German cameraman who has spent perhaps more time than a doctor or mental health professional would strictly advise poring over the crime scene photographs and mugshots from the newly restored police cache—opens with three striking, double-page spreads. First, there’s a set of burglar’s tools, complete with dagger, picks, and a black hat for stealth and style. Next is a shot of the Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges, one of Eugene de Salignac’s famous municipal works images. And then finally, the main event: a man in a trim dark suit, seen from behind, seated at a desk with his forehead pressed down on the wood. It’s a disorienting scene; you might wonder whether the man is napping or posing for a re-creation, if it weren’t for the frame’s title: “Homicide man at desk 1916(?)” He is, of course, dead to rights.

What can a homicide tell us about the life of a place? That’s the question at the heart of Murder in the City. The images found in the basement of 1 Police Plaza spanned decades and depicted some of the most notorious crimes in New York history, but Kaute wisely trains his focus on a single decade, 1910-1920, the earliest days of crime photography and a time when (not coincidentally) newspapers were coming into their modern form.

Spliced into the book, between pages of gruesome deaths and ethereal panoramas, are news clippings from the crime-mad papers of the day, The New York Sun, The Evening World, and The New York Tribune. The headlines alone tell the story of an era: “Woman Strangled to Death Robbed of $2,500 in Jewels at the Martinique,” “Pickpocket Caught and Started a Riot,” “700 Girls Reported Missing to Police in Greater City in Last Six Months.” Some of the clippings fill in the details on the crime scene photographs. For a 1915 image of two men—one black, one white, intermingled, both lying dead with hats at their sides—we learn from The Evening Post’s account that the subjects were suspected burglars who stepped into an open elevator shaft, plunged to their deaths, and were found “locked together in a death embrace.” With other articles, the connection is more ambiguous, though it no doubt enhances our understanding of the city to learn from The Sun that as of May 21, 1915, criminals tended to refer to a revolver as a “rod,” “gat,” or “smoke wagon.”

But the most affecting images in Murder in the City are unadorned and unexplained. A man lies on a carpet at the center of a bare warehouse, his tie folded over his shoulder and his shoelaces undone. The plate reads simply: “Homicide Victim rug warehouse/victim on rug.” For an image of a woman lying dead in an armchair beside a decorated mantle, the police have labeled the setting a “homicide parlor.”

Most haunting of all are the overhead shots, Bertillon’s famous “God’s Eye View.” There’s something undeniably terrible in seeing fresh death from above—a feeling of vertigo takes hold and you notice details, many familiar, that might otherwise have been overlooked, perhaps the better for your peace of mind.

Starting in 1915, police had first access to all murder scenes (previously they’d waited in line behind the coroner), offering detectives a chance to secure the room and set up tripods before anyone else laid hands on the body. From the “God’s Eye View,” we see victims with open eyes, lips parted, blood still in their cheeks and blood spreading over the floor tiles. Often detectives are milling about and the toes of their wingtips poke into the shot. There are unexplained shadows and cigarette butts. It’s not hard to grasp how film noir developed out of these same motifs.

Two decades later, the most famous figure in the history of New York crime photography would emerge: Arthur Fellig, better known as Weegee, the freelancer with the famous eye and a knack for beating even the cops to a homicide. Weegee worked with a Speed Graphic and knew how to title a shot. Among his most famous was “Balcony Seats at a Murder.” Years later, he described how he came to the image: “I got up nine o’clock one night and I says to myself, ‘I’m going to take a nice little ride and work up an appetite.’ I arrived right in the heart of Little Italy, 10 Prince Street. Here’s a guy had been bumped off in the doorway of a little candy store.” Rather than focusing on the body, Weegee stepped back to take in the whole scene: the detectives, the storefronts, the rubbernecking residents out on the fire escapes. It was New York to its core: curious and cruel, a dozen worlds intersecting.

Some time between 1916 and 1920, we don’t know exactly when, the NYPD took an eerily similar shot: a body lies on the sidewalk outside a pasta shop. Overhead—above the laundry, the olive oil importer and the crowded café—are the locals in shirtsleeves and pajamas leaning out their windowsills, looking down on the street. The scene would have been familiar to Weegee. It’s familiar to us, too.

For all the changing styles, New York persists. We live in aging buildings, the sturdiest well over a hundred years old. In the summer we sit on street corners, balconies and rooftops. Who knows how many deaths these locales have hosted? How many detectives have been summoned to the scene? Weegee found art in the daily dramas and tragedies. Before him, and after, the police were on the job. Every now and again their cameras capture something essential about the way we live and die in this city.

__________________________________

All photos copyright 2016 Emons Verlag GmbH, courtesy Thomas Dunne Books.