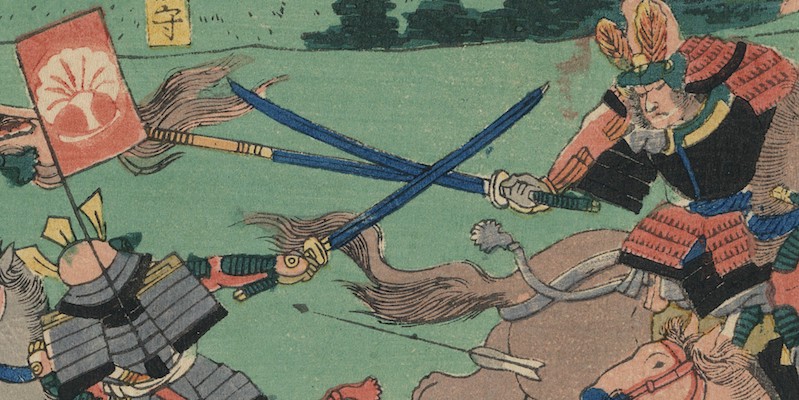

The boxy, seven-story building next door to Tokyo’s famous Ryougoku Sumo Hall stands off the ground on four squat legs, more like an architect’s modern-art version of a bulldog than a museum dedicated to the history of the world’s sixth-largest city. After purchasing a ticket from the window in the left front “leg,” you ride a series of escalators up . . . up . . . up past walls emblazoned with images of Japan’s medieval past: women in elaborate kimono, armored samurai, and villagers in conical straw hats. On the sixth floor, the museum’s inner doors slide open, and you find yourself on a balcony overlooking a massive, full-scale reproduction of the Ryogoku Bridge, which once spanned the Sumida River and served as the official entrance to Tokyo during the early 17th century. As you cross the bridge, you look more than two stories down at two different versions of this famous city.

On the left side of the bridge, a full-sized reproduction of a 17th century kabuki theater rises almost to the top of the bridge. On the right, you see an entire street—a reproduction that dates to shortly after the Meiji restoration of 1868, when the city changed its name from Edo to Tokyo. On the far side of the bridge, the initial gallery contains both artifacts and models of the city throughout history, as well as the escalator that leads down to those full-sized buildings, and many other fascinating, interactive exhibits that make the Edo-Tokyo Museum a fascinating, immersive experience.

As a writer of historical crime fiction, and a general history buff, I’m always looking for new and interesting places to learn about Japan’s medieval past.As a writer of historical crime fiction, and a general history buff, I’m always looking for new and interesting places to learn about Japan’s medieval past. I first discovered the Edo-Tokyo Museum while plotting an upcoming book set in 16th century Tokyo (which was known as Edo until 1868); since then, it has become one of my favorite museum haunts.

The interior of the modern, six-story building is divided roughly in half, with one side dedicated to the history of “Edo” (pre-1868) and the other containing artifacts and exhibits about the modern history of Tokyo. Since my novels take place in the 16th century, I spend most of my time on the Edo side, where the interactive exhibits provide rich fodder for crime fiction.

Life-sized scale models of the row houses once inhabited by members of the common classes (mostly artisans and laborers) let visitors to see how people actually lived in medieval Japanese cities. These long, narrow houses, built of wood, consisted of three to five one-room dwellings, divided by interior walls, beneath a common roof. Each dwelling featured a private entrance, a narrow earthen entry, and a raised interior floor covered by 5-7 tatami mats, making the entire home about the size of a single modern bedroom. Most of these dwelling spaces had no windows, but residents often left the sliding doors open to let in light and air—at least, when the weather permitted.

The museum’s row house displays are furnished with personal artifacts and tools (some original and some reproductions) showing how the various occupants would have lived and worked in these tiny spaces. Best of all, the museum is photograph-friendly, which means I can consult both the museum (via return visits) and my pictures of the exhibits when constructing fictitious row houses for my mystery novels.

Japan has many well-preserved (and reconstructed) castles and samurai mansions, which makes researching the history of the upper class an easy proposition. However, crimes did not only take place among the elite, and the exhibits at the Edo-Tokyo museum are a gold mine for a writer wanting to set a mystery among the common classes—or for anyone curious about how Japanese city-dwellers lived in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Another, equally fascinating series of exhibits focuses on the history of firefighting in Japan. Edo had highly organized firefighting brigades by the 17th century, and the museum has many artifacts on display, from early hand-pump fire extinguishers to the beribboned standards the different fire brigades carried through the streets. There’s even a full-sized reproduction of a fire standard visitors can pick up and carry. (It’s surprisingly heavy.)

the exhibits at the Edo-Tokyo museum are a gold mine for a writer wanting to set a mystery among the common classes—or for anyone curious about how Japanese city-dwellers lived in the 16th and 17th centuries.I first saw the display in 2016, while researching early Edo history for an upcoming mystery novel. Each book in my series involves a different facet of 16th century Japanese culture. I already knew the book in question would take my protagonists—ninja detective Hattori Hiro and Portuguese Jesuit Father Mateo—to the small but growing city of Edo, and visited the Edo-Tokyo Museum in hopes of learning what made the city unique in 1566. The firefighting exhibit reminded me that the city’s many fires (whose causes ranged from accidents to arson) were once referred to as “the blossoms of Edo” which, in turn, inspired the crime in (and the title of) Fires of Edo, currently scheduled for release in 2020.

Even fictitious fires need fuel, and fortunately the Edo-Tokyo Museum inspired me on that score as well. Just beyond the exhibits relating to firefighters, the museum has a collection of hand-copied and early woodblock-printed books, another industry that blossomed in the city now called Tokyo. In addition to the manuscript display, the museum has a life-sized reconstruction of a bookseller’s shop and exhibits with information about the various methods used to create and bind early manuscripts in Japan. Of particular interest to this firebug novelist: the highly flammable glues and traditional papers used in scrolls and books.

Many people are surprised to learn that Japan was one of the first countries to produce bound books with a front and back cover. Scrolls were popular, but not the only means of preserving written records. The earliest “orihon,” or “folding books” appeared in the 8th century, and consisted of sheets of paper folded accordion-style and glued between hard covers.

By the 14th century, Japanese bookbinding techniques had evolved to include “pouch bound” books made by folding sheets of paper in half, stacking them together, and sewing the loose edges together. These double-thick pages allowed the use of thinner paper, and often featured illustrations or woodblock prints as well as words.

The exhibits on display at the Edo-Tokyo Museum include medieval-era manuscripts, woodblock prints, and legal records, each a fascinating glimpse into Japanese history and an excellent inspiration for a novelist in need of something valuable to burn (fictitiously, of course).

The Edo-Tokyo Museum, and others of its kind, preserve not only the history of Japan but also vital elements of the country’s cultural past. Hands-on exhibits make it easier to understand how the artifacts on display were once a functional part of people’s lives and how those same objects could become the basis for fictitious crimes that form the basis of a mystery novel. It’s also a splendid place to spend an afternoon learning about Japan’s historic past.