“Which is better—to have rules and agree, or to hunt and kill?” Piggy asks, in William Golding’s Lord of the Flies. The concept of stranding characters on a deserted island in order to test their humanity and expose their inherent flaws and vulnerabilities is not a new storytelling trope. But, like so many literary themes, for decades the concept has largely been used to shine a light on the souls and inner demons of men.

There have, of course, been some exceptions: like the early science fiction allegory Angel Island by American feminist author, suffragette and journalist Inez Haynes Irwin. The novel, published in 1914, sees a group of men shipwrecked on an island occupied by winged women. They attempt to domesticate the women, then clip their wings, forcing them to remain grounded, until the women eventually rebel to save their daughters from the same fate. But in general, from Robinson Crusoe to The Beach to The Mysterious Island and even in cinematic explorations of the scenario, such as Castaway, the classic, idyllic-yet-dangerous island has remained a man’s world.

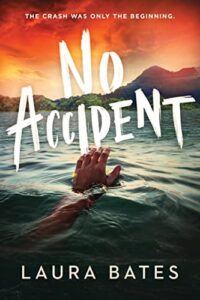

Enter a flurry of new feminist survival thrillers, both in fiction and on screen, including Yellowjackets, The Wilds, and No Accident.

There is clearly a significant current appetite for feminist retellings and gender swapping well-known stories, and it isn’t difficult to see why the idea of giving women a chance to take on the challenges of survival in an inhospitable environment is appealing to a modern audience. (In No Accident, it is the physical strength and gymnastic skill of the female cheerleaders that enables them to access precious coconuts when dehydration threatens their survival, after the jocks have failed to secure any).

Alongside the apparently somewhat belated realisation in Hollywood that teenage girls can have complex, non-stereotypical characters, the juxtaposition of teenage girls with the thriller genre has enabled a satisfying subversion of the classic precious, helpless, image-obsessed cheerleader trope. The Wilds has been praised for its presentation of a diverse, complex cast of characters and for putting queer storylines front and centre, while a character in Yellowjackets grapples with an unwanted pregnancy and weighing the risks of a self-induced abortion. Hardly issues Robinson Crusoe or Chuck Noland ever had to deal with.

The concept of shedding the constraints and expectations of the social contract, previously considered most interesting as a critique of the concept of inherent male morality and nobility, is also ripe for feminist exploration. As Yellowjackets co-creator Ashley Lyle told The Hollywood Reporter: “We thought, who is more socialised than women? As girls, you learn early on how to make people like you and what the social hierarchies are. It’s a more interesting way of having things fall away.”

In a post-#MeToo society, the opportunity to strand characters away from civilisation offers fascinating opportunities to explore current anxieties around misogyny and sexual violence. In The Wilds, researcher Gretchen Klein reveals that the girls’ situation has been deliberately manufactured to explore how society would develop in the absence of patriarchy. (Or, as Entertainment Weekly described it: “a drama about a group of teen girls lured into a fempowerment retreat by an eccentric academic who uses words like “gynotopia”.) It couldn’t be more timely, as online misogynists deliberately stir up manufactured angst about men becoming redundant, left behind and oppressed by a feminist ‘gynocracy’.

The concept also lends itself to natural commentary on our obsession with reality television shows about castaways and deserted islands, especially as characters within The Wilds and No Accident attempt to use their knowledge of TV shows to help them survive, finding that real-life (as well as femininity) is not always quite how it is portrayed on screen.

The stories also often explore the increasing awareness of the intersection of gender inequality and the climate crisis. Megan Hunter’s 2017 novel The End We Start From, soon to be made into a thriller starring Killing Eve’s Jodie Comer, weaves together a dystopian picture of climate devastation with a compelling portrait of survivalist motherhood.

Of course, resorting to a grimly dystopian fictional setting to force a reader or audience to recognise the reality of the violence already happening under their noses is hardly new. While it isn’t a classic desert island scenario, The Handmaid’s Tale could accurately be described as a feminist survival thriller, so dangerous and inhospitable is the environment in which Offred and her female peers find themselves. As Margaret Atwood has famously said: “When I wrote The Handmaid’s Tale, nothing went into it that had not happened in real life somewhere at some time.”

In a world where women are facing devastating threats to their rights, freedoms and bodily autonomy, it is not difficult to see why the allegory of fighting for our very survival remains powerful. The wolf and shark attacks of these recent shows and novels could quite easily be substituted for assaults on women’s liberty by totalitarian regimes, conservative lawmakers and extremist misogynists.

But there is another urgency to this latest slate of stories: it is not a coincidence that they all focus specifically on the battle of teenage girls to survive. We are living in a unique moment, never seen before and never to happen again, where a generation of non-digital natives is parenting and educating a generation of digital natives. The disconnect this has created in terms of adult ignorance of the landscape of teenage girls’ lives and the sexist abuse with which they are bombarded daily cannot be overstated. From an onslaught of unwanted dick pics and demands for nudes to a rise in revenge pornography, deep fakes, online abuse, misogynistic porn, incels, manipulative image filters and so much more, teenage girls are battling to survive. And all while the rest of the world is blithely telling them they are outperforming boys and thriving like no other young women in history.

In the meantime, teen girls look around them and see that there is no justice for their pain. That men who are accused of sexual violence will take some of the highest offices in the land. That the chances of a man they report for rape actually facing criminal charges hovers somewhere in the low single digits. That society will fall over itself to justify and defend the sexual violence of a young man if he has a promising athletic career ahead of him.

There is a frustration and a terror about this drowning in plain sight that translates effectively to the survivalist thriller. This is not an exploration of the inherent savagery within young women themselves, but of the breath-taking, normalised cruelty society inflicts on them. It isn’t that the horror is needed to reflect the subtler reality of teenage girls’ lives, it is that teenage girls’ lives quite literally are a horror story. The rest of the world just doesn’t seem to have noticed.

As Leah puts it in the opening scenes of The Wilds: “If we’re talking about what happened out there, then yeah, there was trauma. But being a teenage girl in normal-ass America, that was the real living hell.”

***